Deficits, Debt, Trade Deficits ... it's all connected

Reading through the reporting in the media and comments on social media, one can’t help but get the sense that there’s a lot of confusion behind terms like deficits, debt, and trade deficits. Let’s disambiguate!

As I’ve pointed out before, it seems that key people in the Trump White House do not understand the balance of payments. But judging by the recent reporting and commentary on social media about tariffs and trade policy, it looks like plenty of others are confused too.

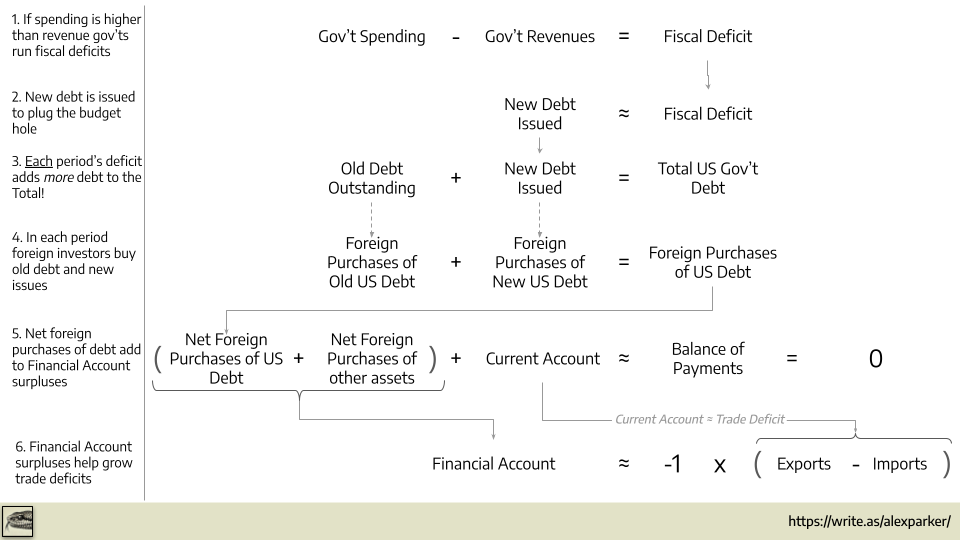

To help, I’ve put together this handy graphic. I’ve tried to do two things. First, offer accurate (if not fully precise) definitions of key terms. And second, perhaps more importantly, show how they all connect.

My thinking is that once you see these concepts in context, they’ll make a lot more sense.

Here’s the graphic:

Walking the diagram: How fiscal deficits drive the trade deficit

Let’s start right at the top and work our way down.

Fiscal deficits occur when government spending exceeds government revenues. At first glance, it might seem like a pure spending problem. But it's worth pointing out that a deficit can arise just as easily from insufficient revenues, i.e., collecting too little in taxes.

New debt is issued to plug the fiscal deficit (or budget gap). In the US, at the federal level, the most common securities are US Treasuries. There are three main flavors based on term length:

- Treasury Bills (T-Bills) mature in less than one year.

- Treasury Notes (T-Notes) have terms between two and ten years.

- Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds) mature in ten to thirty years.

Total US Government Debt grows by the new debt issued to cover that period’s fiscal deficit. A couple of other important points:

- Structural deficits will keep adding to the debt year after year until they’re addressed.

- Eliminating the deficit (i.e., getting it to zero) stops the debt from growing, but it doesn’t shrink the pile.

- Reducing total government debt requires running a fiscal surplus and using that surplus to pay down what’s outstanding.

Foreign purchases of US debt include both newly issued securities and existing bonds traded on secondary markets. Foreign investors are estimated to hold roughly one-third of all outstanding US government debt. Buyers include foreign central banks, asset managers, private financial institutions, and investors of every type.

While obtaining dollar liquidity to facilitate trade and capital flows is one major driver, it’s far from the only one. Consider:

- Global banks and insurers hold US Treasuries in their loss reserves. In some cases, this is required under Basel III and Solvency II.

- Central banks use Treasuries to anchor foreign exchange reserves and support exchange rate stability.

- Institutional investors seek Treasuries for portfolio hedging, yield, and regulatory compliance.

- Treasuries serve as high-quality collateral in repos, swaps, and other global funding markets—even in transactions that don’t involve US counterparties.

As you can see, a big part of the demand for US Treasuries stems from the fact that they’re the “infrastructure” of modern global finance. It’s a big reason why any talk about defaulting on US Treasuries is completely silly.

Net foreign purchases of debt (or when purchases exceed sales of US debt) combine with other net purchases of assets (e.g., equities, corporate bonds, etc.) to contribute to Financial Account surpluses.

Finally, those financial account surpluses are offset by Current Account deficits—that is, trade deficits. Mechanically, when capital flows into the US through the Financial Account, the dollar strengthens, US imports rise, and exports become relatively less competitive, widening the trade deficit.

Shrinking fiscal deficits shrink trade deficits

As the diagram shows, it’s all connected!

Persistent trade deficits are, by definition, the flip side of financial account surpluses. Follow the diagram, when the US runs large fiscal deficits, it must attract foreign capital to fund them. Those inflows bid up the dollar, making imports cheaper and exports less competitive—widening the trade deficit.

That’s why I’ve always found the tariffs über alles strategy really, really peculiar. Even if the tariffs were implemented smoothly and diplomatically, they’d eventually be overwhelmed by the government’s ongoing need to pull in foreign capital. And those capital inflows would buoy the dollar, blunting or even nullifying the intended effect of the import taxes.

If the administration were serious about reducing the trade deficit, it would have started by addressing the fiscal deficit and the debt—because that’s where the imbalance begins. As noted above, shrinking the debt requires running sustained budget surpluses. And that, inescapably, means spending cuts and tax increases.