Erm, does the White House understand the Balance of Payments?

Stephen Miran, a contributor to Trump’s anti-trade strategy, seems to misunderstand the current account deficit. A modest proposal to really address our trade imbalance.

Trump, ever one for simplicity, seems to have stocked his policy bench with men named Stephen—Bannon, Miller, and the lesser-known but no less consequential Stephen Miran.

While a lesser-known member of the Steve Gang, Miran has proven to be quite consequential. Many of his ideas were outlined in his paper, A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System, and these ideas were subsequently used as the academic rationale for the Tariffs Today? Tariffs Tomorrow? Tariffs Forever? strategy favored by Trump, Bessenet, Lutnick, and others.

It’s worth reading the paper yourself, but be warned—it’s a bit like an investment banking deck written by ChatGPT—technically polished, but completely uncanny valley. In fact, whilst reading it, I had a hard time shaking the sensation that Miran does not seem to understand the balance of payments.

Let me explain.

The Balance of Payments is how we account for international flows

The Balance of Payments is how economists track international flows of goods, services, and capital (money). While the formal definition has quite a few terms, the essence of the formula is pretty simple.

\(

\text{Balance of Payments} = 0 ≈ \text{Current Account} + \text{Financial Account}

\)

Where:

- Current Account – Tracks a country’s imports and exports of both services and goods, simplified current account ≈ Exports – Imports. A current account deficit means that imports exceed exports—that's often called the “trade deficit.”

- Financial Account – Tracks cross-border flows of investment—everything from foreign purchases of US assets to American acquisitions abroad.

Given that the balance sums to zero, using the powers of algebra, we can move the terms around and see that:

\(

\text{Financial Account} ≈ – \text{Current Account}

\)

There’s a tight inverse relationship between the two, driven by how international transactions must balance in aggregate, or:

- Current Account deficit can result in a Financial Account surplus

- Financial Account surpluses can result in a Current Account deficit

Still, this is where the argument goes off the rails. Consider Miran’s claim:

“The dollar is overvalued because we have to run deficits to provide reserve assets to the world.”

Erm, not quite. Steve! You’ve got causality running the wrong way.

The dollar isn’t overvalued because we run current account deficits and have to create reserve assets to cover them. No—precisely the opposite. We run current account deficits because the world demands dollar-denominated assets, not the other way around.

Let me explain in a bit more detail.

After the anemic recovery from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis—austerity everywhere, although less in the US—and the COVID-19 shock, global investors piled into safe, dollar-denominated assets. Stocks, bonds, real estate, and especially US Treasuries. Sure, the US was the cleanest dirty shirt. But it was also home to the world’s standout tech giants. Who wouldn’t want a slice of the Magnificent Seven?

All that capital flooding in kept rates low and the money flowing—fueling share buybacks, consumption (imports included), and ever-larger fiscal deficits. Naturally, these inflows also strengthened the dollar, since foreign investors must sell their own currencies to buy dollars before investing in US markets and securities.

The strong dollar is a consequence of global demand for stable—and frankly, pretty attractive—US assets. It's not because we have to buy more imports “to create reserve assets” (good god, what does that even mean!)

That said, Miran’s argument has bigger problems.

- Miran blames the decline of American manufacturing on the strong dollar. This is an extraordinary claim, unsupported by data. As I wrote about here, the US is still a manufacturing powerhouse. In fact, real output is nearly three times higher than during the so-called heyday of American manufacturing in the late 1970s. Thanks to automation and capital investment, we've been able to continue 'making even more stuff' with less than 10% of the US labor force (it's down from ~20%).

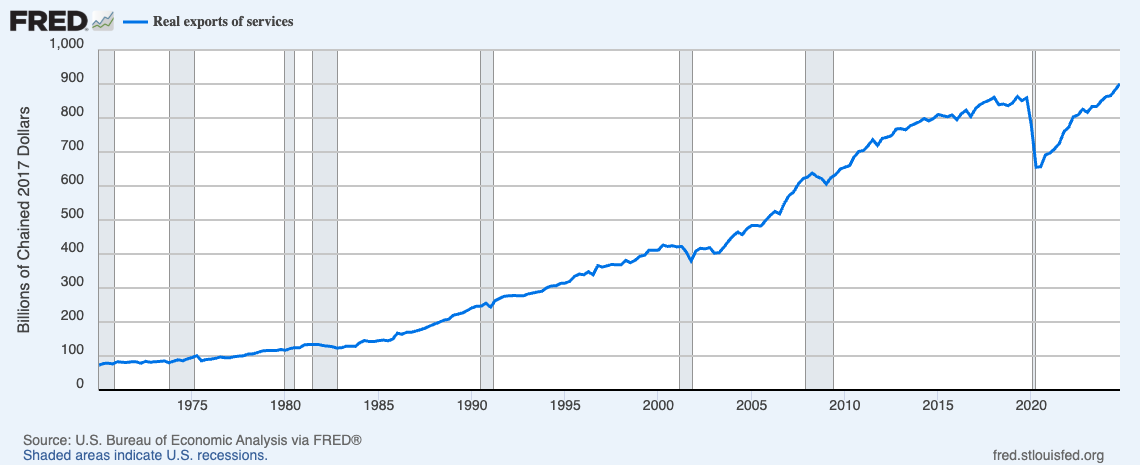

- The “strong dollar” seems to have had very little impact on US services exports. In fact, US Services exports are now ~$1T (twice the next largest exporter, Great Britain).

Setting those minor inconveniences aside, let’s pretend Miran is right (he’s not). Is starting a global trade war really the best way to rebalance trade flows and weaken the US dollar?

Three alternatives to tariffs

Remember the tautology from the previous section on the Balance of Payments:

\(

\text{Financial Account} ≈ – \text{Current Account}

\)

That tautology means reducing foreign purchases of US assets lowers the financial account surplus—and that, in turn, makes it far harder to sustain a current account deficit. Shrink capital inflows, and the trade deficit resolves itself.

Compared to the chaos of a tariff-led global trade war—where the US picks a fight with everyone, a kind of Hobbesian bellum USA contra omnes—cooling foreign demand for US assets seems almost civilized. And far, far less painful.

Some ideas:

Why not ... reduce federal deficits?

The projected US federal deficit is now nearly $2 trillion per year. As most readers know, deficits arise when the federal government spends more than it collects in taxes. To make up the shortfall, it issues debt—mainly in the form of US Treasury Bonds, Notes, and Bills.

Demand for that debt has long been robust across the globe, though it has shown signs of softening in recent years. Still, despite growing concerns over debt levels, deficits, and government dysfunction, foreign investors continue to hold roughly one-third of all outstanding Treasury securities.

Reducing the deficit means issuing fewer Treasuries.

Fewer Treasuries means fewer parking spots for foreign capital.

Reduced foreign investment in US Treasuries shrinks the financial account surplus.

Shrinking the financial account surplus means shrinking the current account deficit.

(n.b. here’s how it all connects)

Even better, with lower supply, Treasury prices would likely rise. Since fixed-income prices move inversely to yields, this would mean lower yields—and a lower interest burden on issued debt.

Getting to a smaller deficit doesn't require the theatrical, nonsensical, chainsaw-wielding incompetence of the kind currently offered by the Department of Government Efficiency. (To be clear, there are plenty of thoughtful cuts worth considering.)

In fact, the most direct and impactful option is simple: repeal the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Undoing that legislation would restore a major source of federal revenue and sharply reduce new Treasury issuance—overnight. How much? Per the Congressional Budget Office, it's roughly $2 trillion over ten years.

Worse, the proposed extension of the Trump tax cuts—estimated to add nearly $5T more in debt—would require enormous inflows of foreign capital, strengthen the dollar and deepen current account deficits even further.

If you want to restore the trade balance, one place to start is simple. Repeal the Trump tax cuts.

How about … eliminating stock buybacks

As the US Treasury points out, foreign investors now own about 17% of all outstanding US equities. One reason US stocks are so attractive? Many firms routinely engage in debt-financed stock buybacks, which keep pushing prices ever higher. Many investors—especially foreign ones focused on price appreciation—love buybacks because they’re an easy way to prop up earnings per share without investing in anything real.

In fact, this “money for nothing” dynamic is exactly why buybacks are heavily restricted in most other markets. The US’s uniquely permissive rules make its equities even more appealing—especially to foreign investors looking for predictable capital gains with minimal friction.

These buybacks are, in part, enabled by foreign capital inflows into US debt markets—where foreign investors hold roughly 20% of all outstanding corporate debt. In other words, firms borrow cheaply (thanks to global demand for US bonds), use the proceeds to buy back their own shares, drive up stock prices, and attract even more foreign investment—both in equity and in debt.

And as we know from the tautology: increased capital inflows (financial account surplus) fuel larger current account deficits. The feedback loop is simple—borrow, buy back, boost prices, attract flows, widen the trade gap.

So, how do we reduce the financial account surplus by making US corporate debt and equity less attractive?

Well, why not ban or severely restrict stock buybacks? Buybacks aren’t investment—they’re shareholder distribution dressed up as strategy. If a company truly has excess capital, it can pay a dividend. If it doesn’t want to dilute, it can issue fewer shares.

And the benefits compound: reducing buybacks makes US equities less appealing to foreign capital. It also reduces the need for corporate borrowing, which lowers foreign inflows into US debt markets. Less capital inflow means a smaller financial account surplus—and that, in turn, gets us back to a balanced trade flows.

What about … a US infrastructure fund

This last idea is admittedly a bit half-baked—and probably deserves a full blog post of its own. But here’s the rough sketch:

Create a domestic infrastructure fund—something akin to Brookfield or Macquarie—that would invest in revenue-generating physical assets: ports, airports, transit, energy, water systems, and so on. But here’s the twist: it would be open only to US citizens, as equity investors, and it would pay dividends, not interest.

Why?

Right now, US citizens compete with foreign investors for the same pool of financial assets—Treasuries, corporate bonds, large-cap equities. That demand contributes to price inflation, keeps yields suppressed, and fuels the very capital inflows that strengthen the dollar and enable persistent trade deficits.

You reduce some of that pressure by giving domestic capital another place to go—a tax-advantaged, yield-bearing, real-asset-backed alternative. You slacken the demand for the more widely traded securities and, in doing so, reduce the feedback loop that currently attracts foreign capital into an overheated financial system.

It wouldn’t eliminate the financial account surplus. But it might shift its structure, which could help narrow the current account deficit over time without tariffs, taxes, or coercion. Plus, making it financial beneficial for citizens to invest broadly in shared infrastructure? It could be a capitalistic approach to chronic underinvestment.

Was Miran writing this age’s Modest Proposal?

If the goal is to reduce the trade deficit, we should start by addressing the financial structures that enable it. That doesn’t mean tariffs, capital controls, or political theatrics. It means reducing fiscal deficits, ending financial engineering disguised as strategy, and creating new places for domestic capital to go.

None of this is radical. It’s just basic macroeconomics. In fact, the answer is so obvious it makes you wonder—was Miran channeling Swift? Was A User’s Guide really a satirical polemic in disguise?

Seriously. Has anyone thought to ask?