Erm, Does the White House understand their policies amplify inflation?

Reviewing exit polling from the 2024 election, it’s clear that one reason Trump was elected was to address inflation. Unfortunately for all those voters, most of the current administration’s policies will raise inflation. Let’s explore how.

Historically, Americans have hired savvy people to manage the nation’s fiscal policy. Why? Because many of us believe that free enterprise and “business” are central to the American character. I’m not alone in that view, as top public servant #30, Calvin Coolidge, once put it:

“The business of America is business.”

But without a stable economic environment, rule of law, and transparency, businesses don’t get built. So, where do we find ourselves on the last day of April 2025?

Well... the current administration is enacting fiscal policies that aren’t just inflationary in the near term. Some of the changes are hard to reverse, and as such, they risk embedding higher inflation expectations permanently into the US economy.

Let me explain.

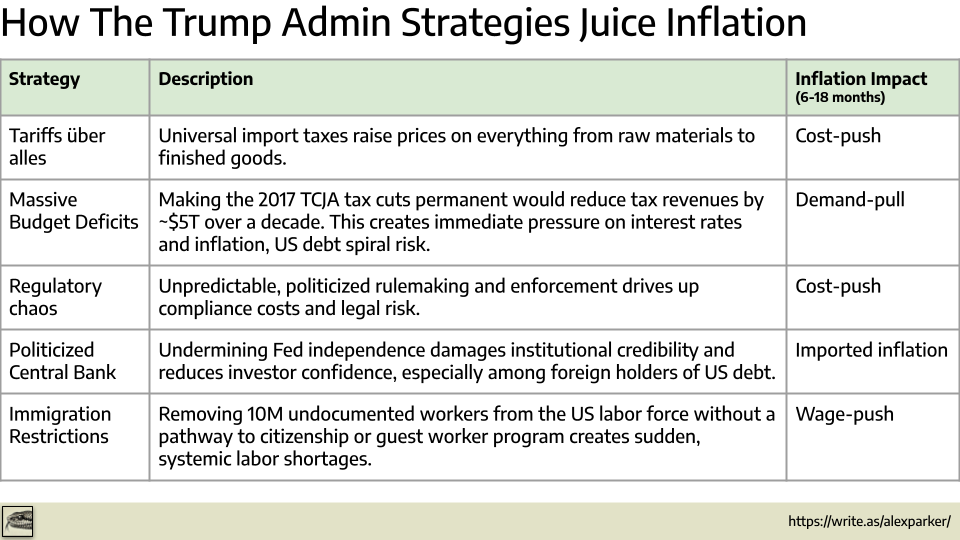

How Trump 2.0 policies are creating structural inflation

Rather than enumerating all fiscal policies, let’s focus on the top strategies and consider their shorter-term impact (6-18 months). And, to be fair, let’s entertain some counterarguments.

Tariffs Über Alles (cost-push ↑)

The immediate and obvious effect of the tariffs is cost-push inflation: higher import costs drive up prices across the board. US importers won’t absorb (or, in the case of Chinese goods, can’t absorb) the full burden of the import taxes imposed by the administration. That means these costs are passed directly to consumers and businesses in the form of higher prices.

It’s also worth pointing out that a significant share of US trade involves intermediate goods—products and parts of products cross borders multiple times during production. American assembled passenger cars are a classic example: components move back and forth across the Canadian and Mexican borders as the vehicle is gradually assembled.

What that means in practice is that some goods are hit by tariffs multiple times (and in unexpected ways). So while the White House may cite a 10% tariff, the effective burden in sectors like auto manufacturing can be far higher, as each crossing triggers another round of import taxes.

Counterpoint: One could argue that higher prices from tariffs will reduce consumption, and that drop in demand would be disinflationary. But this overlooks two critical facts:

Many imported goods have no viable domestic substitutes, e.g., refined rare earths, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and advanced semiconductors. These things aren't manufactured at scale in the US. So consumers and businesses have no choice but to pay more. Second, even when domestic alternatives exist, supply chains and production capacity can’t pivot overnight. Higher tariffs in the short run don’t eliminate demand—they just make goods more expensive, which pushes inflation up before any long-term substitution can occur.

Massive Budget Deficits, Part 1 (demand-pull ↑)

Congressional Republicans have passed a framework to make the 2017 Trump tax cuts permanent, an action projected to reduce tax revenues by roughly $4.5 to $5 trillion over ten years, growing the total debt pile by ~15%. Fiscal injections of this magnitude are classically seen as stoking demand-pull inflation.

The reason is that large tax cuts increase disposable income without a corresponding increase in the economy’s productive capacity (i.e., the supply side). So that excess demand chases limited goods and services. In fact, for the wealthier set who are the recipients of the biggest tax cuts, it would probably look a lot like the “Revenge Spending” of the post-COVID years. Lots of consumer spending with a bit of a debt hangover after the money runs out.

While simply giving more money to consumers isn’t necessarily bad, one could argue that directing such fiscal firepower toward expanding long-term productive capacity would yield more durable benefits. For what it's worth, this is the logic underpinning initiatives like the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and much of the industrial policy pursued by other countries, such as China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. While I’ve tended to shy away from industrial policy, I think it’s a bit undeniable that the investments in science and engineering in many of these countries have proven to be worthwhile.

Counterpoint: Honestly, I’m not sure there is one. Untargeted, pro-cyclical fiscal stimulus in a tight labor and supply environment is inflationary. That’s just textbook macroeconomics. That said, because the US economy is showing signs of weakness, this round of stimulus might moderate a recession or help stave one off, offsetting some of the disinflationary effects that typically accompany downturns. The more realistic outcome, however, is one of lower growth and inflation (stagflation).

Massive Budget Deficits, Part 2 (cost-push ↑)

There’s also an indirect consequence to producing this much debt so quickly: higher rates. And that translates into cost-push inflation.

Historically, a mix of domestic and foreign investors absorbed US issuance, trusting in the country’s stability, institutional sanity, and ironclad contract law. (Those same foreign capital inflows, incidentally, help drive our trade deficits.) But the current administration’s actions have undermined all three of those pillars. Meaning that investors, both foreign and domestic, are questioning the US's creditworthiness, competence, and continuity. It’s a reason why we see rising 10-year yields.

Higher yields mean higher borrowing costs across the economy, as mortgages, corporate bonds, and consumer loans are priced off Treasuries. This drag on fuels a form of cost-push inflation, as businesses raise prices to offset more expensive credit.

Counterpoint: One could argue that higher rates are a healthy market response—a sign of confidence in future growth. But that’s not what we’re seeing. These rising yields aren’t coming from optimism—they’re driven by fear: of fiscal recklessness, political instability, and eroding institutional credibility. When bond investors demand a premium to hold Treasuries, that’s a vote of no confidence.

Regulatory Chaos (cost-push ↑)

While regulation is often dismissed as pure deadweight loss, it’s worth remembering that it can protect the regulated as much as the consumer. Absent corruption, clear regulations delineate the “rules of the game,” helping level the field for smaller, more entrepreneurial challengers competing against entrenched incumbents. Moreover, firms that fully comply with regulatory standards face lower litigation risk and cost. It’s harder to argue negligence and malice when an organization has followed all the rules.

By contrast, the chaotic, corrupt approach to “regulatory reform” the administration is pursuing doesn’t just fuel cost-push inflation—it normalizes bribery as a business expense. Firms inevitably pass along the cost of million dollar Mar-a-lago Dinners and favors paid to administration friends and family. Worse, regulatory uncertainty forces every company, even the politically connected, into a state of permanent siege, never knowing when a shifting political whim will turn them from insider to scapegoat. When “uncertainty about the future” is on the rise, it tends to reduce corporate investment, hiring, and innovation.

Counterpoint: Honestly, it’s challenging to think of any way that increasing government corruption would lead to lower inflation. In principle, reducing the size of the federal workforce could help cut the budget deficit. But here, too, on closer examination, reality intrudes. Eliminating 100% of the civilian federal workforce would only save about $300 billion annually, barely 5% of projected federal spending, and nowhere near enough to offset the massive structural deficits.

Politicized Central Banking (Imported Inflation ↑)

For Americans, one of the most remarkable features of the past eighty years has been the rise of the US dollar to numéraire status globally.

Nearly everything of significance traded across borders is priced in USD, making it the default medium of exchange for much of global trade. As of April 28, 2025, the Atlantic Council’s Dollar Dominance Monitor reported that 57% of global foreign exchange reserves, 54% of export invoicing, and 88% of FX transactions involved the US dollar.

That, in a nutshell, is the inflation-busting “exorbitant privilege” d'Estaing (n.b. not DeGaulle!) and others once warned about.

- From a macro perspective, that outsized utilization of dollars creates foreign demand for USD, driving US financial account surpluses, which sustains persistent fiscal and trade deficits (explainer).

- From a practical perspective, persistent global demand for dollars strengthens it, meaning individual American consumers pay less for imported goods, and businesses pay less for parts, raw materials, and intermediate goods.

One major reason the dollar achieved and has sustained its numéraire status is the United States’ long-standing reputation for stable, nonpartisan monetary policy and the consistent application of the rule of law.

Today, however, and perhaps for the first time in US history, we have a White House that seems intent on politicizing the central bank—and risking the status of the US dollar (and the adjacent status of the US Treasury as the global benchmark for risk-free rates).

Anything that drives countries off the dollar, lowers demand for dollars and weakens the US dollar relative to other currencies. That leads to higher costs on imported goods and inputs for businesses. The result is imported inflation, or rising prices driven by a falling currency.

Counterpoint: None. Politicizing the Fed and undermining the dollar’s global role is a straight shot to higher prices and lower trust. There’s no upside.

Immigration Restrictions (Wage Push ↑)

The strength of the US workforce has always been its ability to absorb and integrate talent from abroad. As of 2023, foreign-born workers made up 18.6% of the US labor force, or about 32.2 million people. Many countries have long complained that US policy was a bit too effective at attracting their top talent and triggering “brain drain” effects.

But this influx of entrepreneurial vigor has paid enormous dividends for the US. Despite being a smaller share of the labor force, foreign-born workers start nearly 25% of all new businesses and are deeply involved in new high-tech ventures, most notably in technical fields.

Within the group of foreign-born workers:

- 23.9 million (13.6% of the total workforce) are here with work authorization: naturalized citizens, H-1B visa holders, agricultural guest workers, and green card holders.

- Roughly half, 11.85 million, are naturalized US citizens with an unambiguous right to work.

- The other 11.85 million are non-citizens working legally under visa or other temporary arrangements.

- The remaining 8.3 million workers, or about 5% of the US workforce, are undocumented. These are the so-called “illegal aliens,” though most have lived and worked in the US for years.

Right now, the Trump administration is working to deport the undocumented while also shrinking or dismantling the programs that allow foreign nationals to work legally in the US (e.g., H-1B, Temporary Protected Status, DACA).

Just looking at the numbers, the practical effect of these policies would be to shrink the workforce by at least 8.3 million workers, or 5%, and potentially as much as 20.15 million, or 11.8%.

And here’s the economic math: the US currently has about 7.1 million unemployed workers. Even assuming perfect skill matching and perfect labor mobility (which does not exist)

- Deporting all undocumented workers would leave a net labor shortage of 1.2 million people, and

- If legal workers are also restricted, the gap could balloon to over 13 million unfilled jobs.

The result would be massive labor shortages and wage inflation. This shortage would probably also accelerate offshoring, not for cost savings, but because the domestic workforce simply isn’t large enough to get the work done.

Counterpoint: Unfortunately, from an economic perspective, even deporting a relatively small percentage of undocumented workers would result in significant wage-push inflation. There is no serious macroeconomic argument that mass deportation would reduce inflationary pressures in the labor market—it would amplify them.

Individually? It’s a Bad Policy. Combined? It’s Stagflation.

Each of the current policies amplifies inflation on its own. Combined, they create a layered, self-reinforcing structure that compounds inflationary pressures and makes it increasingly likely that sustained, high inflation expectations become embedded in the US economy.

Now, that’s not even the worst macroeconomic outcome imaginable. That would be a Japanese-style deflationary spiral: a liquidity trap with no pricing power, no growth, and no clear escape. But that’s not where the US is headed under the Trump administration’s current policy mix. Instead, the far more likely result is stagflation:

- Systemic inflation, driven by tariffs, deficits, and imported cost pressures.

- Weakened demand, as real wages fall and labor market disruptions (shortages+) mount.

- Lower investment, as firms hesitate to deploy capital in a legal environment marked by regulatory chaos, uncertainty, and political caprice.

In short, businesses don’t invest where the rule of law feels brittle and the customer base is under pressure.

If the experience of the 1970s and early 1980s is any guide, escape may require the hard way: a politically insulated Federal Reserve willing to impose real pain to restore price stability.

But there’s a big problem.

During Volcker’s era, US debt hovered around 30% of GDP. Today, it’s over 120%. That makes any future tightening cycle vastly more painful. The interest burden on federal debt will balloon, crowding out other spending and amplifying the contractionary effects of higher rates. It could also force broad-based, sudden tax hikes just to keep the lights on.

Fun, this will not be. ¯\(ツ)/¯

It’s ironic that over the past eighty years, the United States built the most powerful economy in world history on three pillars: rule of law, transparency, and stability. This administration is actively burning all three to the ground and calling it greatness.

Then again, I suppose there’s a certain grandeur in orchestrating economic collapse at scale.