In case you haven't noticed America still makes stuff

For decades conventional wisdom has been that the US is bereft of manufacturing, Loads of folks claim “We no longer make things,” but is that really the case?

You’ve probably heard the call: “Bring back American manufacturing!” It’s become chapter and verse in the American political hymnal—sung in harmony by everyone across the political spectrum.

In fact, restoring US manufacturing has become the the pretext for the Trump administration’s Caligulaic drive to weaken the dollar—via a stagflationary spiral and a tariffs über alles approach.

Inciting a recession is strong medicine—the economic equivalent of chemotherapy. But before we commit to poisoning consumer spending, excising key parts of the federal government, freezing our export sector, and irradiating the dollar into oblivion… shouldn’t we first diagnose the patient?

Is US manufacturing really stage four, in need of heroic intervention?

So let’s ask, when, exactly, did American manufacturing go away?

The truth is, manufacturing never left.

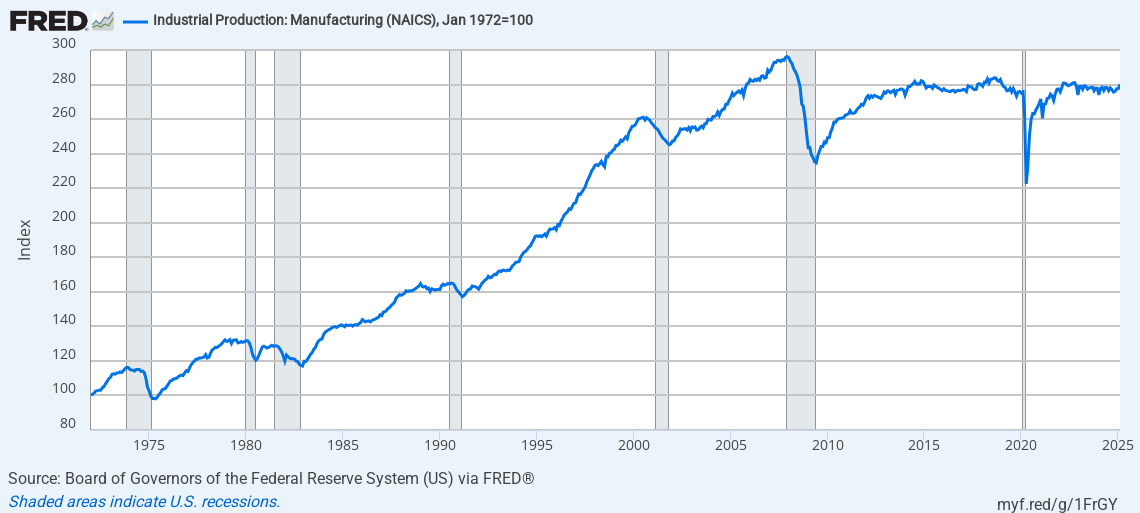

For the time being the Federal Reserve publishes a monthly index of industrial production which measures real output for manufacturing, mining, and electric and gas utilities. From this series, we can isolate the Manufacturing component—and what we find is striking. Since January 1972, US manufacturing output has grown nearly 2.8 times in real, or inflation adjusted terms.

But all that aside, what does it really mean that US manufacturing output has nearly tripled since the 1970s?

It’s means we’re still an industrial giant.

Pre-pandemic, West and Lansang over at Brookings pointed out that the US was the 2nd largest manufacturing economy in the world. Post-pandemic, according to the most recent World Bank data, the US is still firmly holding the number two spot behind China. That recovery, which you can see in the graph above, was due in no small part to the $4 trillion and $1.9 trillion in stimulus provided by the Trump and Biden administrations during the pandemic—stimulus that helped businesses weather supply chain disruptions and kept workers from leaving the industry altogether.

Just how big is being number two?

Well, Grabow over at Cato Foundation noted that with ~16% of global output, the US has a greater share of manufacturing than Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined.

The National Association of Manufacturers puts it more bluntly. If the US manufacturing sector was its own country, it would be the seventh-largest economy in the world.

Or—we never stopped making things, we just make fewer than China.

Output got swole. Jobs got skinny.

But then why does the phrase “manufacturing is dead” resonate so strongly with the body politic?

The biggest reason is that there are far fewer people that work in manufacturing today than in 1972. In fact, employment has steadily declined over the past forty years. As Harris wrote in a 2019 overview from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics:

In June 1979, manufacturing employment reached an all-time peak of 19.6 million. In June 2019, employment was at 12.8 million, down 6.7 million or 35 percent from the all-time peak.

But it's also worth keeping in mind that manufacturing employment doesn't exist in a vacuum. While manufacturing employment has been falling, the US population and labor force has been growing . The result is, as a share of total private employment, manufacturing now makes up less than 10% of total private employment—down from nearly 25% in the late 1970s

In the chart above, the blue line is manufacturing employment, which is plotted against the left axis. The red line is manufacturing employment as a percentage of total private sector employment, it’s plotted against the right axis.

How we made more

There are many reasons for the long decline in manufacturing employment—among them, shifts in what the US manufactures. But perhaps the most important reason is automation. It’s how we’ve managed to produce more with fewer people. In fact, since the 1970s, output per manufacturing worker has more than doubled.

Automation at this scale is possible because the United States has the deepest financial markets in the world. That access to capital enables US manufacturers to invest in new machinery, tools, and technologies that boost output while reducing the number of workers required on the factory floor.

For most of the period since 1970, capital investment and automation were the engines of productivity growth. That productivity engine began to sputter in the 2010s—likely a lagging consequence of the weak, austerity-choked recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. And in my view, that’s a key reason why productivity gains have flattened since.

And automation isn’t just possible—it’s necessary—because US employees tend to be well-educated, skilled, and comparatively expensive.

How much more expensive?

- In the US, the average hourly wage of a non-supervisory manufacturing employee is about $27.35.

- In China, it's roughly $7.00 an hour—assuming an annual wage of 97,500 CNY, a 2,080-hour work year, and an exchange rate of 7.25 CNY/USD.

- In Mexico, it’s lower still—roughly $4.00 an hour.

- In Bangladesh, it’s closer to $0.70 an hour—assuming $113 a month, and 160 hour work month.

Automation is how we continue to be the second largest manufacturing economy. It's why our manufacturing footprint continues to grow. But it’s also why so many manufacturing jobs disappeared.

No Sledgehammer Needed

Given the facts, US manufacturing is in great shape. Employment may be down, but output is up—and before the recent Trump admin shenanigans, it was still growing.

The sector has seen a wave of investment, much of it driven by the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021), and the CHIPS and Science Act. New factories are going up. Supply chains are being rethought—not out of desperation, but out of opportunity.

Let’s be plain: There is no need for the toxic cocktail of economic chemotherapy being prescribed by the Trump administration—mass tariffs, industrial autarky, and a deliberate recession. That prescription simply doesn’t match the facts on the ground.

Okay, fine, you might say—I agree. We don’t need that kind of medicine.

But shouldn’t we make more?

I’d say yes, and you and I wouldn’t be alone. There’s growing support from all kinds of people who think that we should be expanding manufacturing. The motivations vary, but they often include:

- Public health types who still remember the pandemic-era shortages of masks, PPE, swabs, ventilator parts, and essential drugs.

- Defense planners and policymakers worry about critical dependencies on geopolitical rivals—especially China—for everything from rare earths and semiconductors to antibiotics and drone motors.

- Unions—especially in legacy manufacturing states—see a resurgence in domestic production as a path to high-wage, high-skill, middle-class jobs.

So the will is there. The question isn’t can we make more—it’s whether we’ll do it wisely.

But that’s a question for another post.