Making sense of the latest PDPA amendments to the Consent Obligation

This post is part of a series relating to the amendments to the Personal Data Protection Act in Singapore in 2020. Check out the main post for more articles!

Introduction

The history of data protection legislation, in my view, comprises three generations:

- The earliest generation focuses on common law and sectoral self-regulation. It’s a bit of the wild west, with various ideas and strands all over the place.

- The EU’s Data Protection Directive, way back in 1995, represents the next generation. Its key innovation is comprehensive national legislation. Its foundations are based on OECD recommendations and revolve around consent, notification, purpose limitation, etc.

- The third and latest generation, of course, belongs to the GDPR in 2018. Its key innovations are lawful purposes, protection of children, the right to be forgotten, the right to object to automated processing, etc.

Singapore’s PDPA was enacted in 2012. It sits between the EU’s Data Protection Directive and the GDPR. As such, it retains many well-established and familiar features but very few of the innovations used in the GDPR.

One of these artefacts concerns what the PDPA calls the “consent obligation”. The consent obligation requires the consent of a data object before an organisation can process personal data. Unfortunately, reality does not work out like that. As is consistent with experience, data subjects in Singapore don’t “consent” much substantively, and the exception swallows the rule. Other laws, the exceptions in the schedules of the PDPA and the “reasonable” requirement all qualify the consent obligation.

Instead of looking to the GDPR, the latest amendments to the PDPA “double down” on the consent obligation. Sure, the schedules will undergo some housekeeping and streamlining. Deemed consent is expanded. Two new exceptions are introduced — legitimate interests and business improvement. (Curiously “legitimate interests”; sounds like one of the legal bases in the GDPR.)

Given the Law Reform Committee’s view that the PDPA is sound, the consent obligation will be with us for a long time.

A flow chart to understand the Consent Obligation

As I showed above, I am not a big fan of this convoluted consent obligation. I like the legal bases of the GDPR more. They are easier to explain, and the exceptions don’t control the rule. By conceding that consent is unable to explain user rights fully, the GDPR accords better to reality.

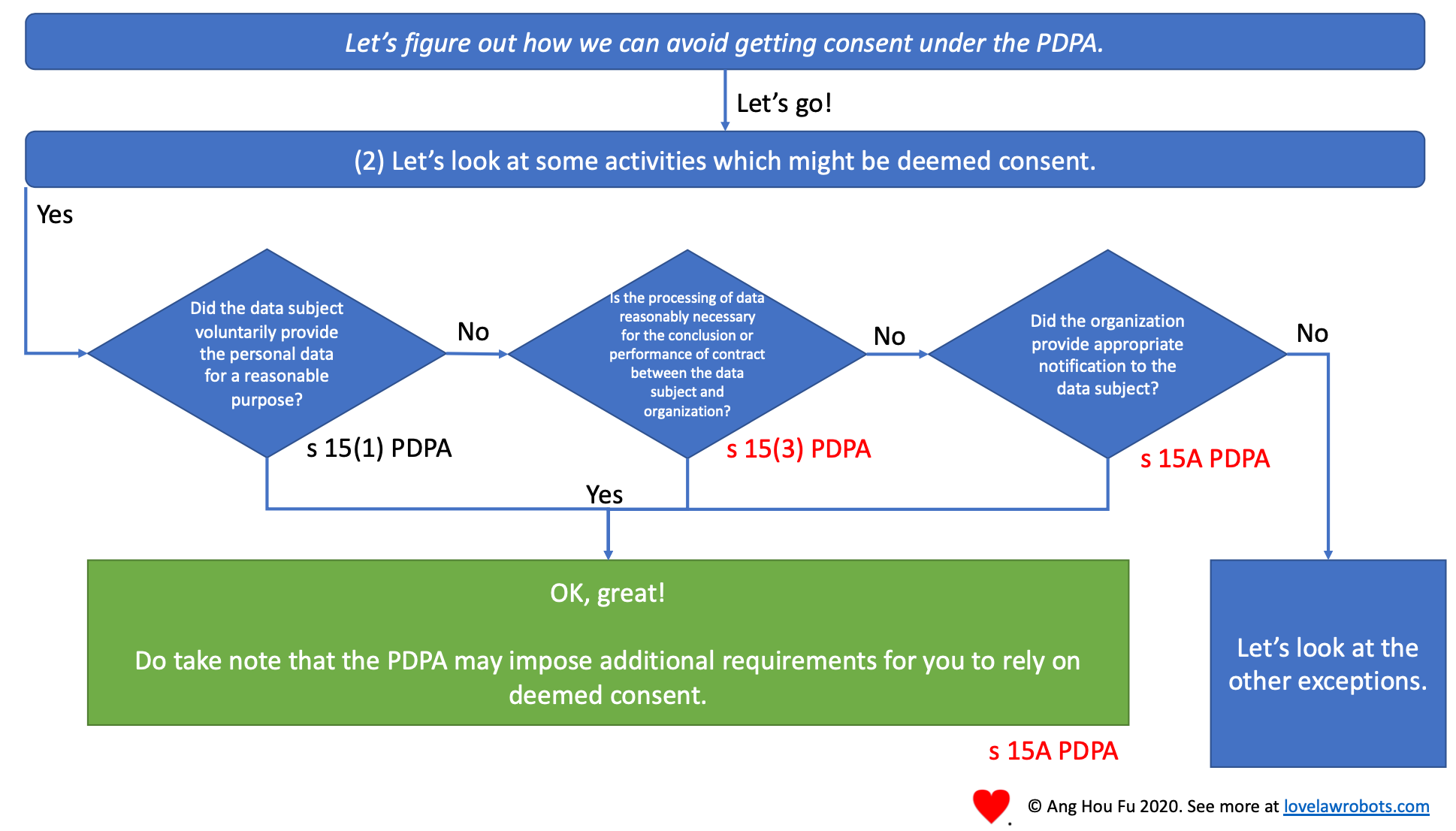

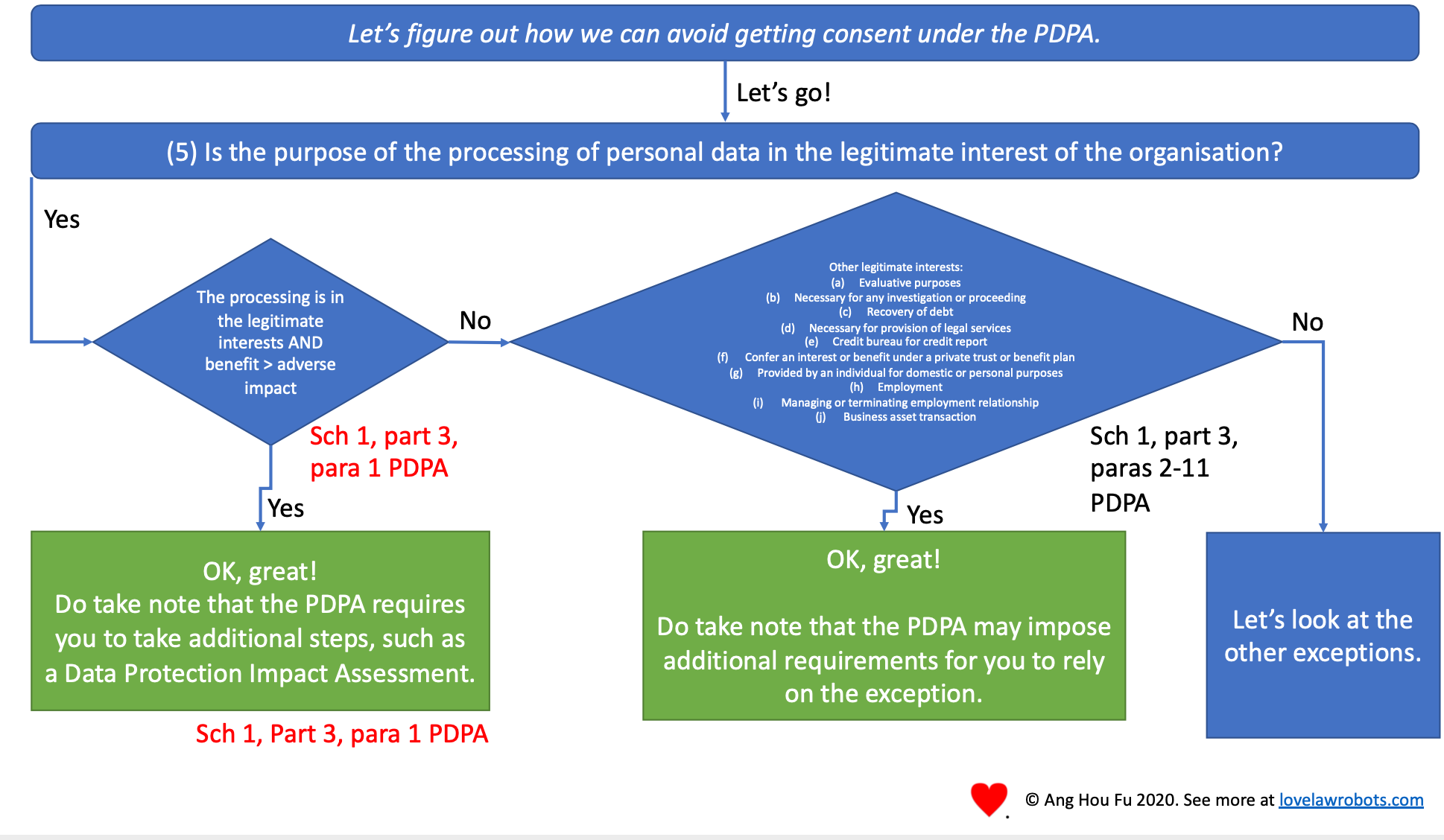

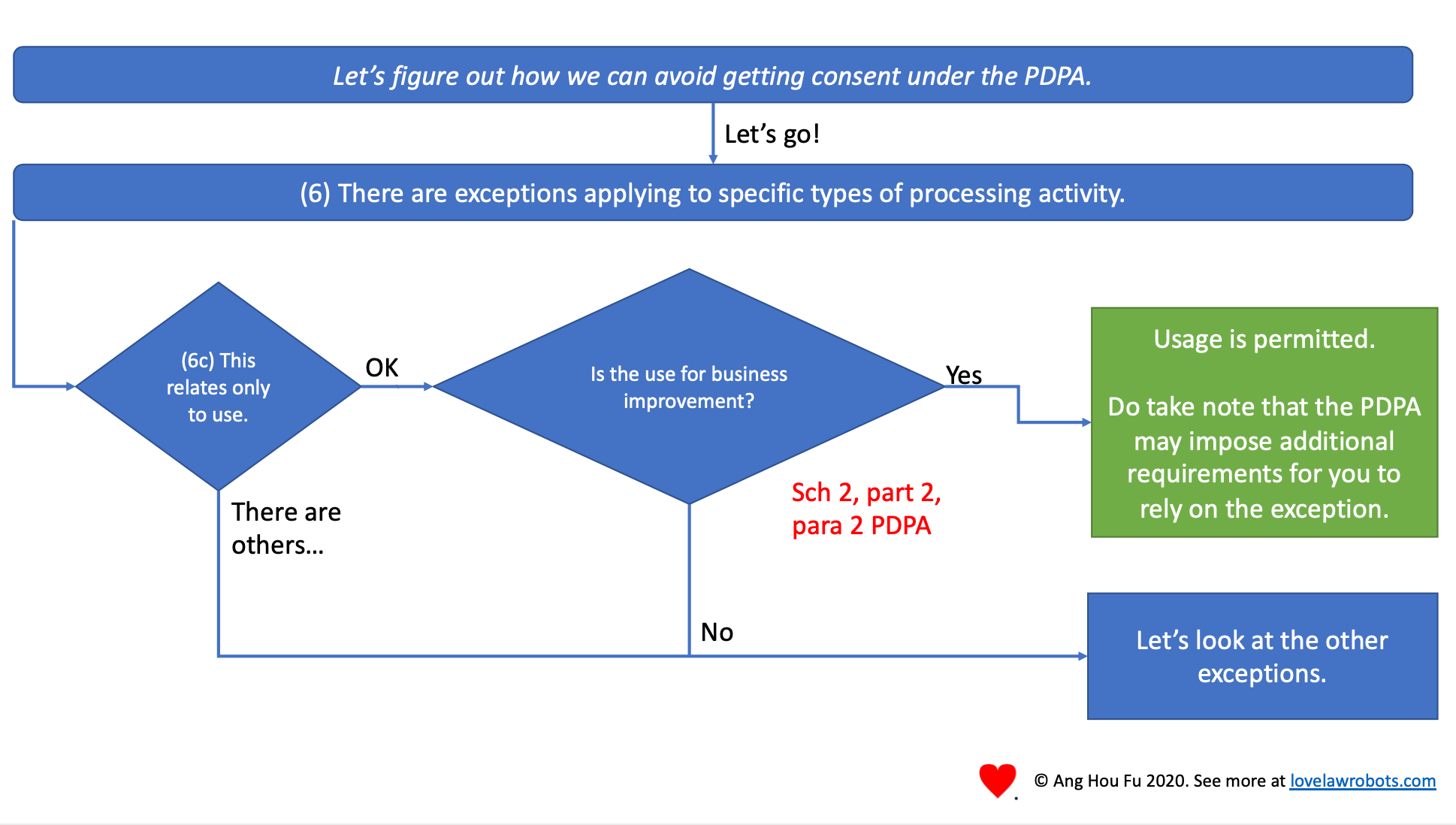

Nevertheless, I am going to try to explain the Consent Obligation, including the new amendments. So, we are going to play a game! Let’s play “ so you want to collect personal data in Singapore “.

Highlights of changes

As I summarized above, there are several new exceptions to the consent obligation. Here are some highlights.

Deemed consent has expanded.

Deemed consent has expanded.

Deemed consent has grown with two new situations. They are expansive and encompass many cases where it’s evident that organisations should have sought consent. The appropriate notification situation also enables organisations to use another method of obtaining consent, which may be considered less confrontational.

A new legitimate interests exception.

A new legitimate interests exception.

The PDPA will also feature a new general exception for legitimate interests. The one in the PDPA looks similar to the one in the GDPR. It also requires organisations to do a cost-benefit analysis in the form of a data protection impact analysis.

Here is another one: using personal data for business improvement. As this only applies to use, you must have collected the personal data through other means. This applies very much to data and customer analytics. You might have already collected data from your customers or operations, and this allows you to make more use of it without worrying about the PDPA.

Conclusion

The changes to the consent obligation are very business-friendly. Should an organisation be excited to employ these exceptions?

If you have been very much at the top of your privacy game, you probably would not need any of these exceptions. Your privacy policy would already have included using personal data for data analytics or business improvement. You would not be needing any “deemed consent” because, in line with best practices, you would have already been upfront and direct with your data subject.

Given the hit or miss nature of PDPC decisions when exceptions are considered, if you can plan for it, you wouldn’t rely on any of these exceptions.

So while it’s heartening to see the movement from openness to accountability, these new changes represent a step back. Hopefully, I wouldn’t need to add several more pages to the next version of my flow chart.

#Privacy #Singapore ##PDPAAmendment2020 #ConsentObligation #GDPR

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow [this blog on the Fediverse]()

- Contact me: