Mining PDFs to obtain better text from Decisions

This post is part of a series on my Data Science journey with PDPC Decisions. Check it out for more posts on visualisations, natural language processing, data extraction and processing!

This post is the latest one dealing with creating a corpus out of the decisions of the Personal Data Protection Commission of Singapore. However, this time I believe I got it right. If I don’t turn out to be an ardent perfectionist, I might have a working corpus.

Problem Statement

I must have written this a dozen of times here already. Law reports in Singapore unfortunately are generally available in PDF format. There is a web format accessible from LawNet, but it is neither free as in beer nor free as in libre. You have to work with PDFs to create a solution that is probably not burdened with copyrights.

However, text extracted from PDFs can look like crap. It’s not the PDF’s fault. PDFs are designed to look the same on any computer. Thus a PDF comprises of a bunch of text boxes and containers rather than paragraphs and headers. If the text extractor is merely reading the text boxes, the results will not look pretty. See an example below:

The operator, in the mistaken belief that the three statements belonged

to the same individual, removed the envelope from the reject bin and

moved it to the main bin. Further, the operator completed the QC form

in a way that showed that the number of “successful” and rejected

Page 3 of 7

B.

(i)

(ii)

9.

(iii)

envelopes tallied with the expected total from the run. As the envelope

was no longer in the reject bin, the second and third layers of checks

were by-passed, and the envelope was sent out without anyone realising

that it contained two extra statements. The manual completion of the QC

form by the operator to show that the number of successful and rejected

envelopes tallied allowed this to go undetected.

Those lines are broken up with new lines by the way. So the computer reads the line in a way that showed that the number of “successful” and rejected, and then wonders “rejected” what?! The rest of the story continues about seven lines away. None of this makes sense to a human, let alone a computer.

Previous workarounds were... unimpressive

Most beginning data science books advise programmers to using regular expressions as a way to clean the text. This allowed me to choose what to keep and reject in the text. I then joined up the lines to form a paragraph. This was the subject of Get rid of the muff: pre-processing PDPC Decisions.

As mentioned in that post, I was very bothered with removing useful content such as paragraph numbers. Furthermore, it was very tiring playing whack a-mole figuring out which regular expression to use to remove a line. The results were not good enough for me, as several errors continued to persist in the text.

Not wanting to play whack-a-mole, I decided to train a model to read lines and make a guess as to what lines to keep or remove. This was the subject of First forays into natural language processing — get rid of a line or keep it? The model was surprisingly accurate and managed to capture most of what I thought should be removed.

However, the model was quite big, and the processing was also slow. While using natural language processing was certainly less manual, I was just getting results I would have obtained if I had worked harder at regular expressions. This method was still not satisfactory for me.

I needed a new approach.

A breakthrough — focus on the layout rather than the content

I was browsing Github issues on PDFMiner when it hit me like a brick. The issue author had asked how to get the font data of a text on PDFMiner.

I then realised that I had another option other than removing text more effectively or efficiently.

Readers don’t read documents by reading lines and deciding whether to ignore them or not. The layout — the way the text is arranged and the way it looks visually — informs the reader about the structure of the document.

Therefore, if I knew how the document was laid out, I could determine its structure based on observing its rules.

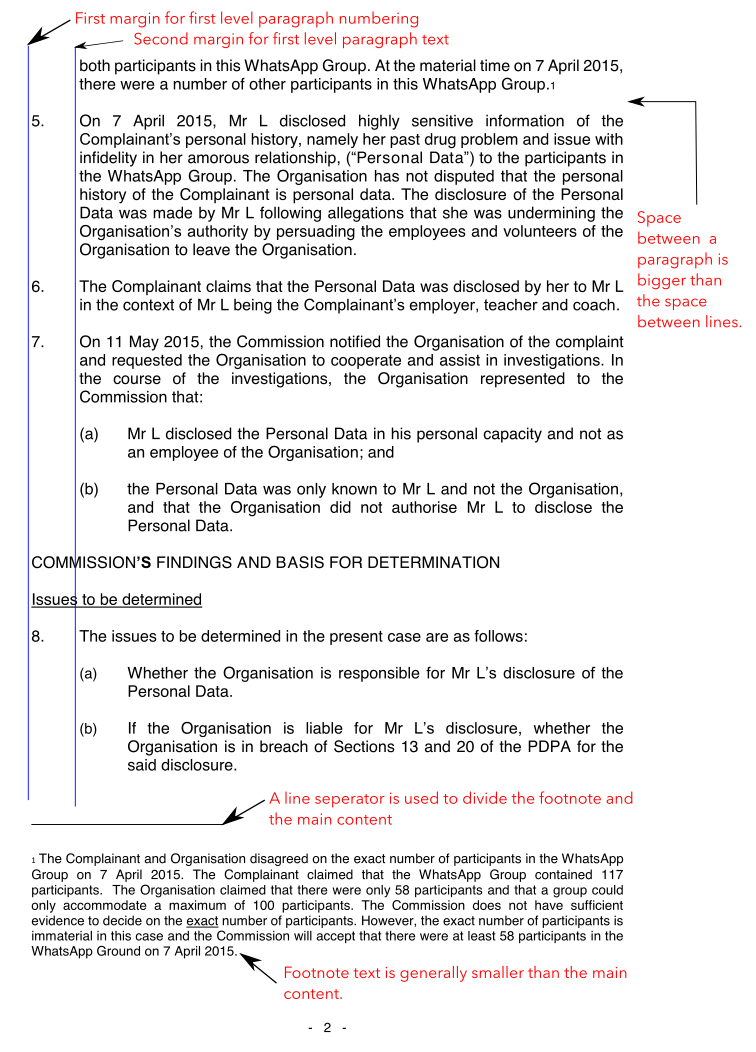

Useful layout information to analyse the structure of a PDF.

Useful layout information to analyse the structure of a PDF.

Rather than relying only on the content of the text to decide whether to keep or remove text, you now also have access to information about what it looks like to the reader. The document’s structure is now available to you!

Information on the structure also allows you to improve the meaning of the text. For example, I replaced the footnote of a text with its actual text so that the proximity of the footnote is closer to where it was supposed to be read rather than finding it at the bottom of page. This makes the text more meaningful to a computer.

Using PDFMiner to access layout information

To access the layout information of the text in a PDF, unfortunately, you need to understand the inner workings of a PDF document. Fortunately, PDFMiner simplifies this and provides it in a Python-friendly manner.

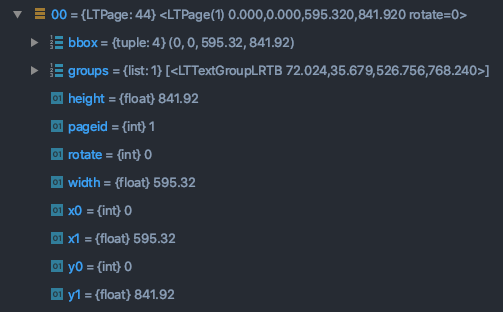

Your first port of call is to extract the page of the PDF as an LTPage. You can use the high level function extract_pages for this.

Once you extract the page, you will be able to access the text objects as a list of containers. That’s right — using list comprehension and generators will allow you to access the containers themselves.

Once you have access to each container in PDFMiner, the metadata can be found in its properties.

The properties of a LTPage reveal its layout information.

The properties of a LTPage reveal its layout information.

It is not apparent from the documentation, so studying the source code itself can be very useful.

Code Highlights

Here are some highlights and tips from my experience so far implementing this method using PDFMiner.

Consider adjusting LAParams first

Before trying to rummage through your text boxes in the PDF, pay attention to the layout parameters which PDFMiner uses to extract text. Parameters like line, word, and char margin determine how PDFMiner groups texts together. Effectively setting these parameters can help you to just extract the text.

Notwithstanding, I did not use LAParams as much for this project. This is because the PDFs in my collection can be very arbitrary in terms of layout. Asking PDFMiner to generalise in this situation did not lead to satisfactory results. For example, PDFMiner would try to join lines together in some instances and not be able to in others. As such, processing the text boxes line by line was safer.

Retrieving text margin information as a list

As mentioned in the diagram above, margin information can be used to separate the paragraph numbers from their text. The original method of using a regular expression to detect paragraph numbers had the risk of raising false positives.

The x0 property of an LTTextBoxContainer represents its left co-ordinate, which is its left margin. Assuming you had a list of LTTextBoxContainers (perhaps extracted from a page), a simple list comprehension will get you all the left margins of the text.

from collections import Counter

from pdfminer.high_level import extract_pages

from pdfminer.layout import LTTextContainer, LAParams

limit = 1 # Set a limit if you want to remove uncommon margins

first_page = extract_pages(pdf, page_numbers=[0], laparams=LAParams(line_margin=0.1, char_margin=3.5))

containers = [container for container in first_page if isinstance(container, LTTextContainer)]

text_margins = [round(container.x0) for container in containers]

c = Counter(text_margins)

sorted_text_margins = sorted([margin for margin, count in c.most_common() if count > limit])</code></pre>

Counting the number of times a text margin occurs is also useful to eliminate elements that do not belong to the main text, such as titles and sometimes headers and footers.

You also get a hierarchy by sorting the margins from left to right. This is useful for separating first-level text from the second-level, and so on.

Using the gaps between lines to determine if there is a paragraph break

As mentioned in the diagram above, the gap between lines can be used to determine if the next line is a new paragraph.

In PDFMiner as well as PDF, the x/y coordinate system of a page starts from its lower-left corner (0,0). The gap between the current container and the one immediately before it is between the current container’s y1 (the current container’s top) and the previous container’s y0 (the previous container’s base). Conversely, the gap between the current container and the one immediately after is the current container’s y0 (the current container’s base) and the next container’s y1 (the next container’s top)

Therefore, if we have a list of LTTextBoxContainers, we can write a function to determine if there is a bigger gap.

def check_gap_before_after_container(containers: List[LTTextContainer], index: int) -> bool:

index_before = index - 1

index_after = index + 1

gap_before = round(containers[index_before].y1 - containers[index].y0)

gap_after = round(containers[index].y1 - containers[index_after].y0)

return gap_after >= gap_before

Therefore if the function returns true, we know that the current container is the last line of the paragraph. As I would then save the paragraph and start a new one, keeping the paragraph content as close to the original as possible.

Retrieve footnotes with the help of the footnote separator

As mentioned in the diagram, footnotes are generally smaller than the main text, so you could get footnotes by comparing the height of the main text with that of the footnotes. However, this method is not so reliable because some small text may not be footnotes (figure captions?).

For this document, the footnotes are contained below a separator, which looks like a line. As such, our first task is to locate this line on the page. In my PDF file, another layout object, LTRect, describes lines. An LTRect with a height of less than 1 point appears not as a rectangle, but as a line!

if footnote_line_container := [container for container in page if all([

isinstance(container, LTRect),

container.height < 1,

container.y0 < 350,

container.width < 150,

round(container.x0) == text_margins[0]

])]:

footnote_line_container = sorted(footnote_line_container, key=lambda container: container.y0)

footnote_line = footnote_line_container[0].y0

Once we have obtained the y0 coordinate of the LTRect, we know that any text box under this line is a footnote. This accords with the intention of the maker of the document, which is sometimes Microsoft Word!

You might notice that I have placed several other conditions to determine whether a line is indeed a footnote marker. It turns out that LTRects are also used to mark underlined text. The extra conditions I added are the length of the line (container.width < 150), whether the line is at the top or bottom half of the page (container.y0 < 350), and that it is in line with the leftmost margin of the text (round(container.x0) == text_margins[0]).

For Python programming, I also found using the built-in all() and any() to be useful in improving the readability of the code if I have several conditions.

I also liked using a new feature in the latest 3.8 version of Python: the walrus operator! The code above might not work for you if you are on a different version.

Conclusion

Note that we are reverse-engineering the PDF document. This means that getting perfect results is very difficult, and you would probably need to try several times to deal with the side effects of your rules and conditions. The code which I developed for pdpc-decisions can look quite complicated and it is still under development!

Given a choice, I would prefer using documents where the document’s structure is apparent (like web pages). However, such an option may not be available depending on your sources. For complicated materials like court judgements, studying the structure of a PDF can pay dividends. Hopefully, some of the ideas in this post will get you thinking about how to exploit such information more effectively.

#PDPC-Decisions #NaturalLanguageProcessing #PDFMiner #Python #Programming

Love.Law.Robots. – A blog by Ang Hou Fu

- Discuss... this Post

- If you found this post useful, or like my work, a tip is always appreciated:

- Follow [this blog on the Fediverse]()

- Contact me: