AI Concepts Learning Tool

This exercise grew out of some thoughts about where I’m going with my fascination with artificial intelligence – an interest that, while still relatively new for me, has settled quickly into something serious and absorbing.

Working in a library, there’s a strong argument that I should be in a position to make AI literacy part of my work, even if I can’t explore it all day. Libraries are, at their core, about access to information and the ability to make sense of it, and AI feels like a natural extension of that remit. If I’m genuinely interested and reasonably knowledgeable, I’m likely to be more effective at it than someone approaching it as a box-ticking exercise.

But there’s also a quieter tension underneath that justification: I’m envious of people who get to do this full-time. That raises a more interesting question than professional relevance. If I did have unlimited time, what would I want to do with AI? Learn and experiment for its own sake? Build things? Teach others? Or something else entirely?

Which leads to a more practical problem: what is the next thing I want to learn, or get better at? I’m still deeply interested in prompt engineering, but I’ve started to feel its limits as a learning focus. I don’t want to abandon it so much as move beyond it and understand more clearly what else sits around it.

The answer lies somewhere between building things and stepping back to understand what’s happening underneath. Making things – as with the prompt engineering exercise – teaches how these systems behave in a visceral way that reading about them doesn’t. But on its own, that kind of learning risks staying shallow.

What I was looking for was a way to pair hands-on experimentation with a clearer grasp of the underlying ideas: how AI systems are structured, what they’re doing conceptually, and where their limitations lie. The appeal was in letting practical experimentation and conceptual understanding inform each other, so that experiments would sharpen my understanding and, in turn, influence my approach to future experimentation.

Turning my attention to building things, the question became: what would be small and functional enough to be manageable, but still useful, instructive, or simply enjoyable to make?

My AI assistant for this exercise, Anthropic’s Claude, suggested a range of possibilities: a mood tracker, a decision-making tool, a simple game, an interactive story, a learning quiz on a topic I cared about, or a tool for organising my AI learning notes.

The proposed process was straightforward. I would describe what I wanted, Claude would build it, I would use it and see what was missing or not working, and we would iterate from there. In doing so, I’d start to learn how to think in terms of features and user flow, what was technically possible, and how to debug things when they didn’t behave as expected.

Concepts could be explained as they arose naturally during the build, or we could pause for more focused deep dives on specific topics, giving concrete context to ideas that might otherwise remain abstract.

When I talk about Claude building something for me to use, I’m referring to what Anthropic calls an artifact. These are interactive elements that live alongside the conversation in a separate panel, or can be viewed in full-screen mode. Artifacts aren’t standalone applications that can be distributed or installed elsewhere. They exist entirely within the interface itself, persisting inside the conversation in which they were created, but can be reopened and used directly from the artifacts section in Claude’s sidebar.

The most natural artifact for me to try to build was a learning tool focused on understanding AI concepts. I settled on a quiz or revision-style tool, on the assumption that it could help me learn in two distinct ways. First, through the act of designing it: deciding which topics and concepts to include, how to structure questions, and what makes for a clear and useful explanation. And second, through using it in practice, by quizzing myself and revisiting ideas that needed reinforcing.

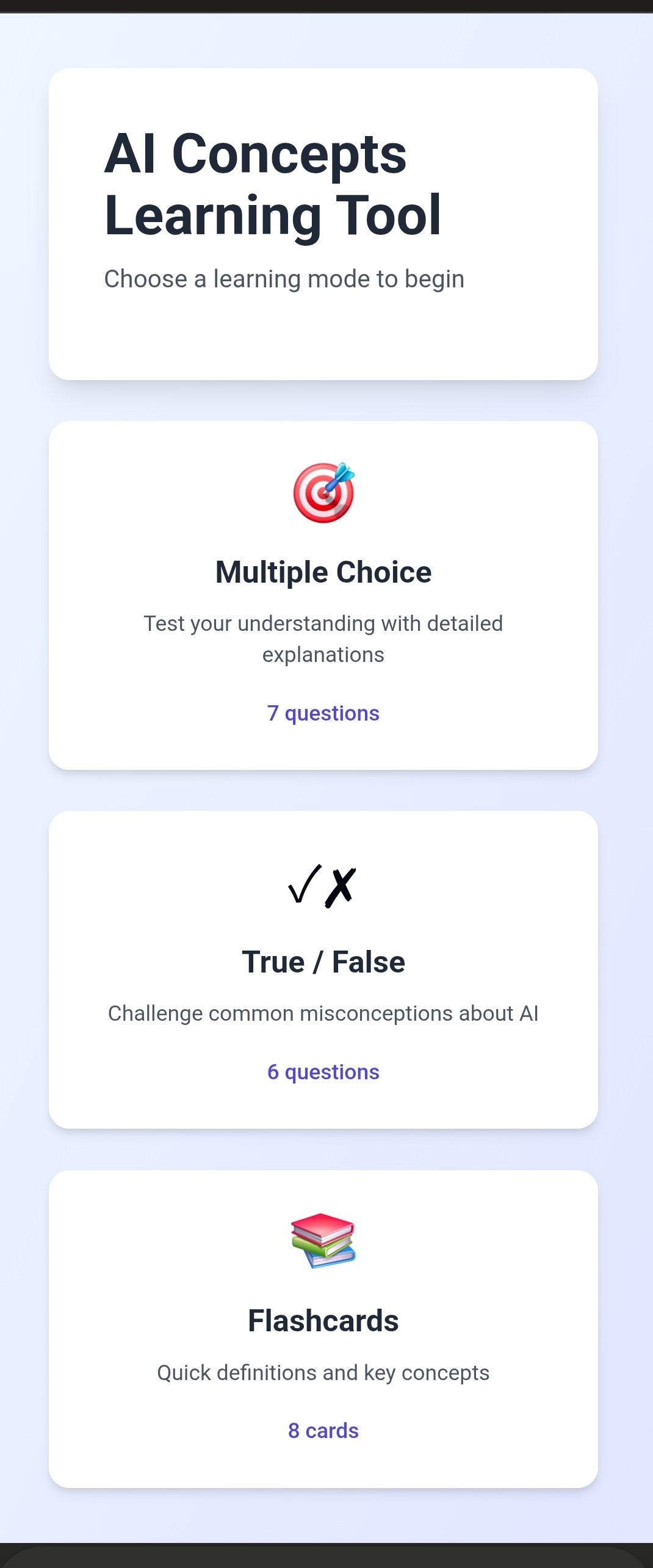

The intention was to begin simply and build the project up over time, adding new topics as my knowledge develops. The format itself could be refined as I learned what best supported my own learning. We started with a blend of three quiz formats: multiple-choice questions with explanations, flashcards with a concept on one side and its explanation on the other, and true-or-false questions accompanied by more detailed breakdowns.

I suggested a few topics I wanted to understand more clearly, and Claude proposed others designed to provide a solid foundation, covering both how models work and how to use them effectively. We chose to build the tool so that I could select which format to practise, track which questions I’d already seen, view explanations after answering, and mark specific concepts for further review.

When Claude created the learning tool, a panel opened alongside our conversation showing the code being written in real time. Claude told me it was built in React, with Tailwind CSS handling the visual design. What emerged was a complete, functional application that ran directly in my browser. I could interact with it immediately, without needing to install anything or understand the code itself.

The artifact demonstrated how AI can translate a conversational description of intent into working software. I described what I wanted in plain English, which Claude converted into functional code. The whole process took minutes, and the result was immediately usable. I didn’t need to understand the code for the tool to work, but it was there to inspect if I wanted to learn from it or modify it.

In practice, the move from idea to functional thing didn’t unfold as iteratively as I’d imagined. After a brief discussion, Claude produced a working version of the tool more or less immediately. There was no prolonged back-and-forth, no slow refinement, no debugging phase to wrestle with. Instead, I found myself holding a finished thing far sooner than expected.

That speed was surprising. What appeared almost instantly was not a sketch or a rough prototype, but a concrete tool that already served a real purpose: a learning resource capable of helping me retain and revisit key concepts. The usual sense of working towards something was largely absent.

This made something else clearer by contrast. The real work had happened earlier, in the act of describing what I wanted with enough clarity for the tool to exist at all. The process of specifying intent – thinking through purpose, structure, and use – did more work than I had anticipated, while the effort of construction itself was almost entirely abstracted away.

In this, working with AI became a very direct experience of leverage. In the classical sense, a lever doesn’t remove the weight of an object; it changes where and how effort is applied. The force still has to come from somewhere, but it’s redirected to a point where a smaller input produces a larger effect.

The object didn’t get lighter: a functional learning tool still had to exist. But the effort didn’t vanish – it moved upstream. The point of leverage became specification, intent, and judgement, rather than construction. What surprised me wasn’t just the speed, but the absence of resistance where I expected it. I anticipated struggle during building; instead, any strain appeared earlier, in deciding what the thing should be and articulating it clearly enough to exist.

When the work of execution becomes almost effortless, the moment of ‘making’ stops feeling like a journey and starts feeling like a switch being thrown. It can feel both exhilarating and oddly final.