Revisiting Dan Dare

Partly to get inspiration for Foolish Earth Creatures, but mostly because everything is terrible and life is too short not to unashamedly indulge in things that bring you joy, I’ve been reading through my collected editions Dan Dare: Pilot of the Future. This is one of my main inspirations for my WIP and also one of my favourite works generally, so I thought I’d write a personal reflection on it, like I did a while ago with the Foundation series.

This is going to be a personal blog post about a thing that I like. It doesn’t contain much concrete information about my next game, so feel free to skip it if that’s what you’re here for. I’ll release a normal dev diary towards the end of the month.

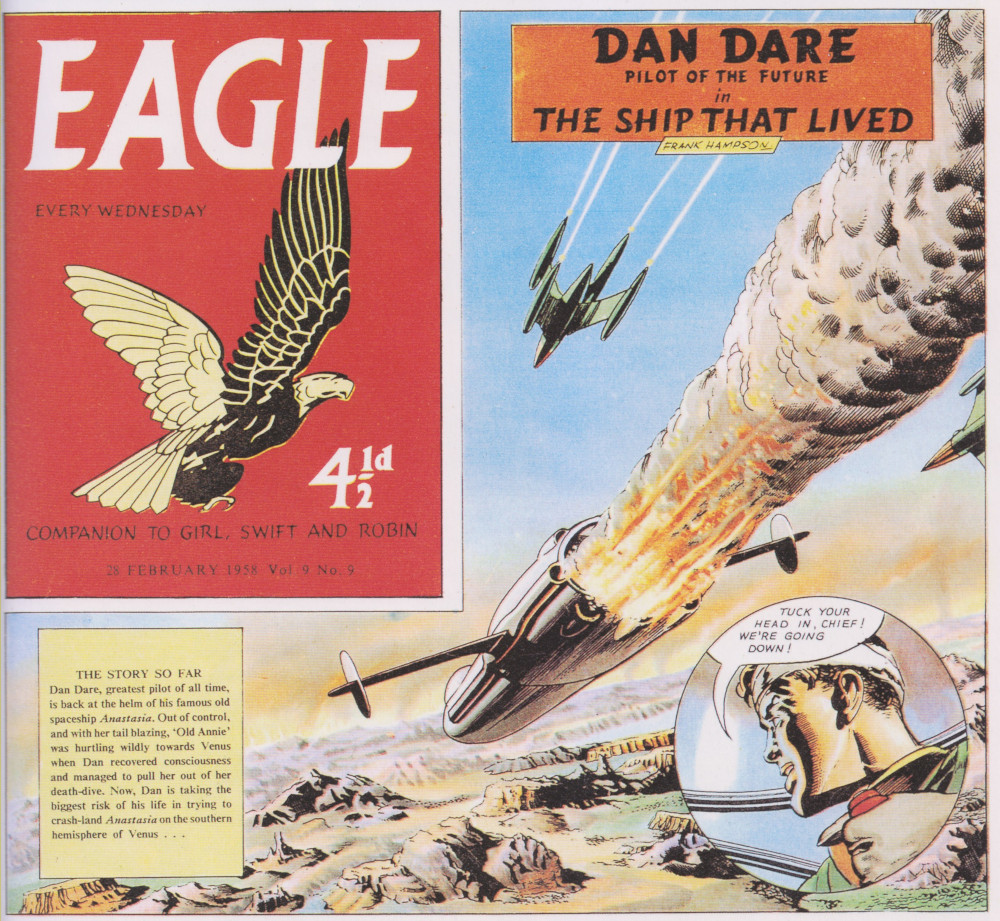

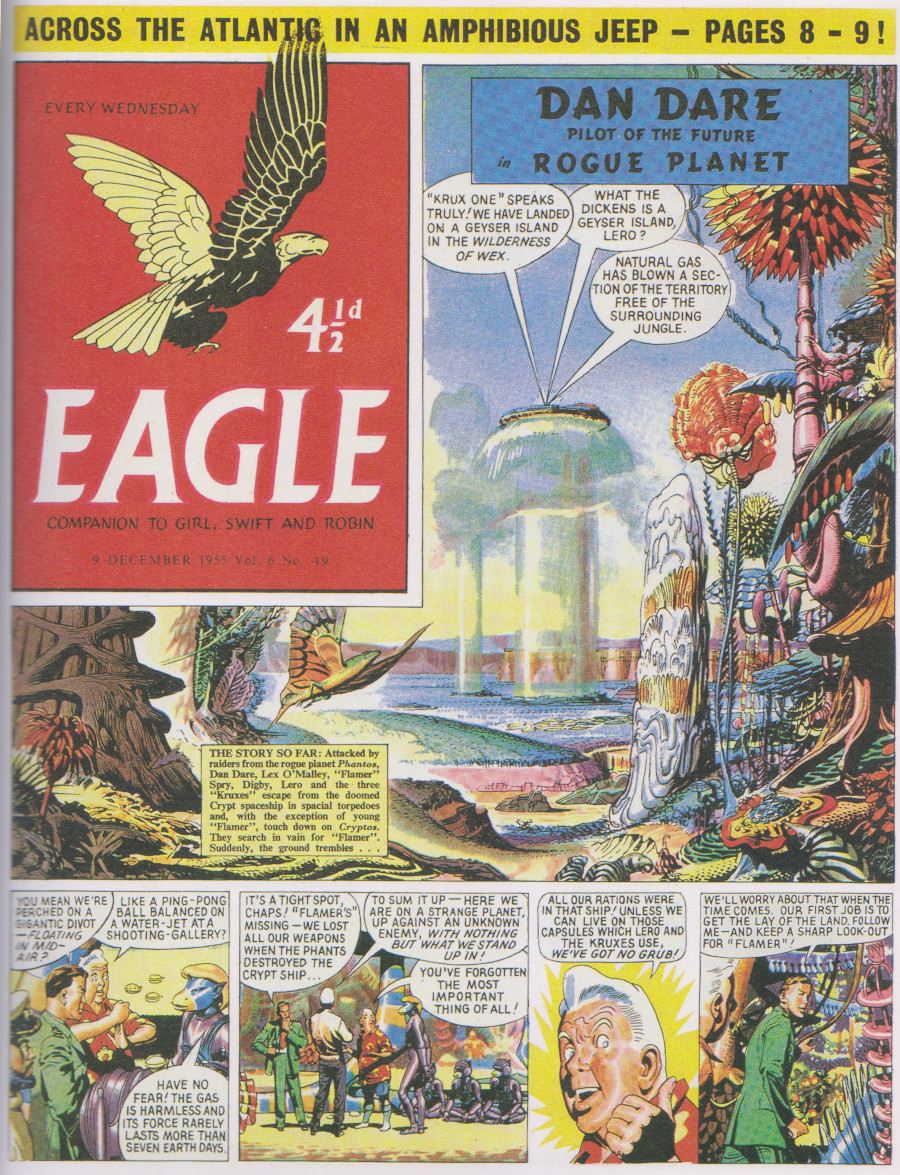

Dan Dare was a comic strip that ran in the British Eagle comic from 1950 to 1967, about a space pilot who explores the solar system and defends its peoples from various threats, in particular his arch-nemesis the Mekon. I’m not quite old enough to have read it when it first came out, but I was exactly the right age for it around 1990 when my dad brought home some big hardback volumes reprinting some of the original strips. I became obsessed with the exciting, colourful stories, and they had a big impact on my developing imagination.

So, does Dan Dare hold up, 75 years after it was first published? And does it hold up for me, 35 years after I first read it?

Absolutely yes, on both counts.

The artwork is beautiful, well ahead of its time and easily standing up alongside modern comics. Not only was its creator, Frank Hampson, a talented artist, but he also had a ‘studio system’ where he worked with a team of assistants and used photographic and model references. That combination of talent and resources is rare, and the love and effort that went into the artwork shows through on every page.

Hampson said that he drew the strips with the assumption that readers would read them twice: once quickly to take in the story, and then again more slowly to enjoy the artwork. (That may not be how kids these days read comics, but remember this was 1950s Britain and there was very little else to do.) When I first read the stories at age 8 I was too impatient not to read straight through, but this time I forced myself to slow down, and it really is a joy to examine the art and drink in the details.

(I mean, look at the level of detail in this alien jungle. In particular note the stripey elephant-like creatures in the bottom right: there are some of these hidden on every page, until the characters eventually adopt one as a team pet.)

The stories expertly balance weekly cliffhangers with satisfying long-term story arcs, some of which ran for over a year of weekly two-page episodes. They’re children’s adventure stories with all the ridiculousness that that implies, but within that genre they’re well-constructed, plausible, and sometimes surprisingly mature. There are a few cracks that become visible if you read them all in one go rather than week by week (contrived coincidences, mysteries that end up never getting explained), but not many.

An Anti-Fascist Hero

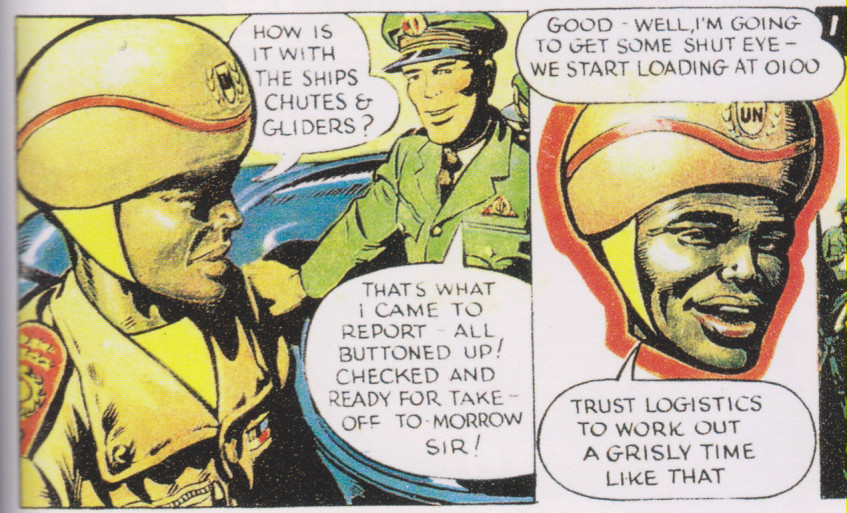

Dan Dare was created a few years after the Second World War, by people who served in that war. The Spacefleet uniforms are based on British Army uniforms, and some of the spaceships resemble WW2 bombers. The villains aren’t as visually Nazi-coded as, say, the Empire from Star Wars, but they’re usually authoritarian overlords who see their people as a superior race and who want to enslave or destroy lesser races. So it’s easy to read these stories as re-enacting the Second World War in space.

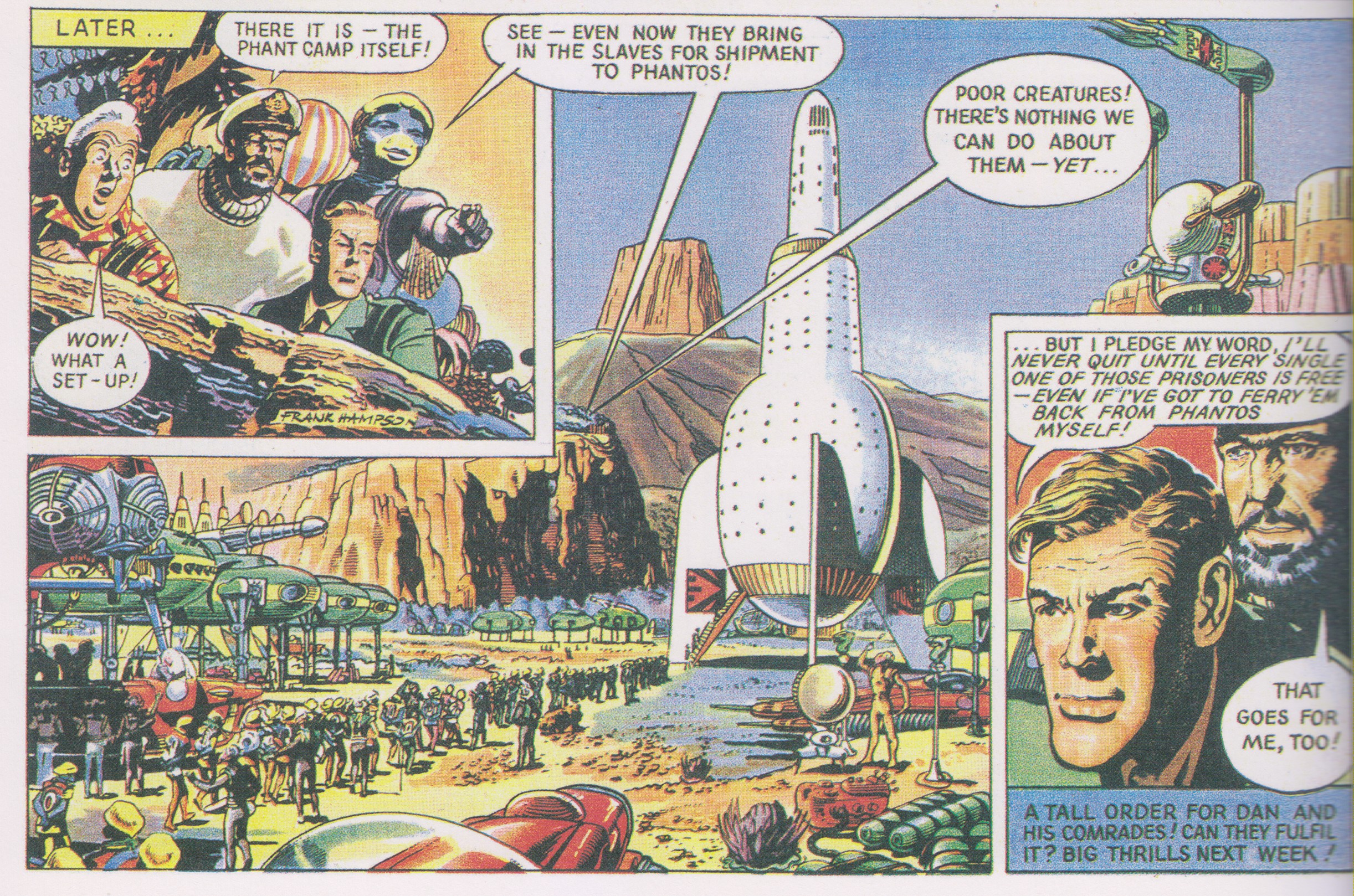

But if this is WW2 in space, the emphasis is very much on ‘liberating the world from fascism’, not ‘defending our shores from foreigners.’ These are never xenophobic stories about Dan Dare defending Earth from inherently evil aliens. Usually they feature one group of aliens being oppressed by another, and Dan will fight to free these unfamiliar aliens from oppression, often by joining up with some kind of local resistance movement. The bad aliens may also have some plan to conquer the Earth, but this almost feels like it’s beside the point to Dan Dare. Even the ‘bad guy’ aliens aren’t presented as inherently evil, but as victims of their villainous overlords, and they are usually able to live peacefully with their neighbours once that overlord is removed.

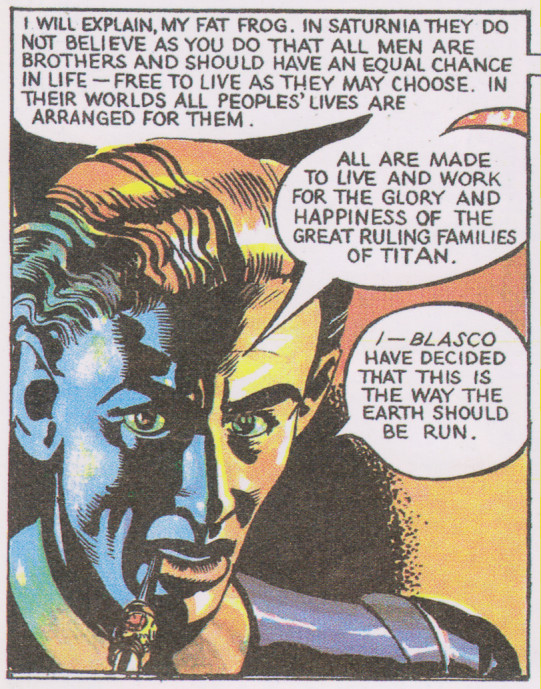

An Optimistic Future

When Dan Dare is defending the Earth, the Earth he’s defending is peaceful, multicultural, and prosperous, with a unified government that’s explicitly descended from the United Nations. (The UN branding is everywhere; when Dan gives an inspiring speech at the end of the first story, it’s not in front of a Union Jack or some made-up future Earth flag, but in front of the real blue-and-white UN flag.) The UN was only a few years old when Dan Dare appeared, and the story imagines a world in which all the most utopian dreams around its founding came true. “We get a world government that ends wars, the doctors have nearly every disease taped, and nobody’s really poor any more,” one character explains in an early issue. The first story is set in the relatively near future of 1995 (within the readers’ expected lifetimes), and there are enough hints about the history of the intervening years to make its world seem, if not likely, at least possible.

“In Saturnia they do not believe as you do that all men are brothers and should have an equal chance in life,” complains Doctor Blasco, the secondary villain of Operation Saturn, a frustrated aristocrat who thinks it’s his birthright to rule over lesser people. Everyone besides Blasco’s tiny cabal of henchmen finds his views to be abhorrent, which is why he has to go all the way to Saturn to find allies to support his goals.

“In Saturnia they do not believe as you do that all men are brothers and should have an equal chance in life,” complains Doctor Blasco, the secondary villain of Operation Saturn, a frustrated aristocrat who thinks it’s his birthright to rule over lesser people. Everyone besides Blasco’s tiny cabal of henchmen finds his views to be abhorrent, which is why he has to go all the way to Saturn to find allies to support his goals.

But this was a story by British writers for a British audience, so this multicultural united Earth is viewed through a British lens. The World Government is politically descended from the UN, but it sometimes seems to be culturally descended from the British Empire. Four of the six main cast members of the first story are British, the other two being American and French. The impression I get is that it’s trying to balance depicting a united world with making most of the cast British in order to appeal to the British audience. You could say a similar thing about e.g. Star Trek, with its theoretically multicultural future that actually looks predominantly American.

Also, despite the professed values of universal brotherhood, the 1950s British class system is alive and well. Dan Dare’s sidekick Digby is his batman (i.e. a serviceman assigned to an officer as a personal servant), and their dynamic is ‘gentleman and his valet’ rather than ‘pilot and co-pilot,’ which for me is one of the things that makes the story feel most uncomfortably dated.

Progressive for its day (but that day was 1950)

There’s only one major female character in the whole run, space scientist Professor Jocelyn Peabody. But she's a critical member of the team, every bit as brave and competent the men, and is not anyone’s love interest. Science fiction of the 1940s and 50s rarely had female characters who weren’t someone’s wife or girlfriend, so even having one was notable for the time. In fact the first story was self-consciously anti-sexist, with a sub-plot about another character underestimating Peabody because of her sex but getting over it after she proved herself calm in a crisis.

Unsurprisingly, everyone in the main cast is white, although the first story does have a person of colour in the small but important role of commander of the UN army, one of the few people Dan defers to as a superior. And whereas there’s a sub-plot about an old-fashioned man having trouble working with a woman, no one in the UN army seems to be bothered about taking orders from a Black man.

Maybe this is me projecting my own values back onto my favourite stories, but my impression is that Frank Hampson was being as progressive as he could get away with in his time. (Apparently he wanted to include a Russian character in addition to the American and the Frenchman, but this was nixed by the publisher; I can only imagine that having a non-white person or more than one woman on the main cast would have been a non-starter.) But if he was trying to be progressive in the first story, he seems to stop trying after that, as there are no new women or POC characters for the whole rest of the run.

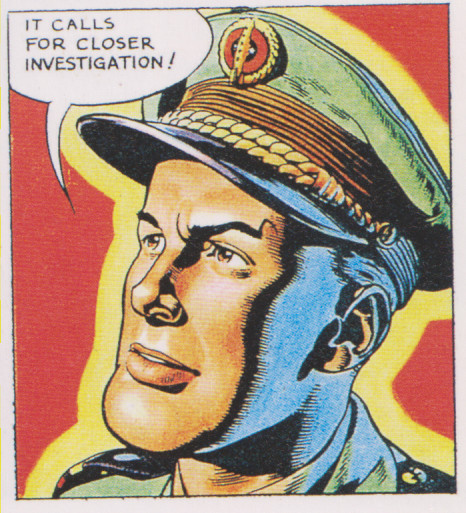

The Ideal Space Hero

The Eagle was created by an Anglican vicar who wanted to make a wholesome alternative to what he saw as the overly violent ‘horror comics’ being imported from America. One of the early concepts for Dan Dare had him as a military chaplain in space, before they settled on him being a pilot.

Reading the stories while knowing this, I found it surprising that there’s very little explicit religion in them. Dan Dare may have been intended to embody Christian values, but the text never identifies them as Christian values. You can equally well read him as just being a good person.

And Dan Dare is about as morally upstanding as someone can get while still just about managing to be a believable character. He’s compassionate, honourable, and curious; he never gives up even against seemingly insurmountable odds, and faces apparently certain death with stoic acceptance. (“While there's life, there's hope,” as characters sometimes say to one another while sinking into boiling quicksand or facing down an alien ray gun.) He tries to understand his enemies and find peaceful solutions, but will use violence when he has to. I think what saves him from being a one-note boy scout type character is that the stories also depict how difficult it can sometimes be to stick to your principles in tough situations, and how his idealism and sense of honour can let enemies manipulate him, leading to characters with more flexible morals having to step in to save the day.

And Dan Dare is about as morally upstanding as someone can get while still just about managing to be a believable character. He’s compassionate, honourable, and curious; he never gives up even against seemingly insurmountable odds, and faces apparently certain death with stoic acceptance. (“While there's life, there's hope,” as characters sometimes say to one another while sinking into boiling quicksand or facing down an alien ray gun.) He tries to understand his enemies and find peaceful solutions, but will use violence when he has to. I think what saves him from being a one-note boy scout type character is that the stories also depict how difficult it can sometimes be to stick to your principles in tough situations, and how his idealism and sense of honour can let enemies manipulate him, leading to characters with more flexible morals having to step in to save the day.

He’s also a thrill-seeker who gets bored whenever he’s stuck behind a desk rather than going on space adventures. He’s brave but pragmatic, and his code of honour isn’t one that stops him from backing down from a fight he doesn’t think he can win. When he does fight, he tends to use ju-jitsu moves to use larger enemies’ momentum against them. Despite starring in a story that’s named after him, he’s very much a team player who both respects his colleagues’ skills and enjoys their company. He smokes a pipe, something that is strange seeing a young hero character do today, but was a common habit among RAF pilots back then. He’s devoted to Spacefleet, and something I noticed when re-reading is that he always wears full uniform whenever the plot allows it, even when other characters don’t. (Someone else might use being lost in an alien jungle as an excuse to take off their tie, but not Dan Dare.)

Vince Gilligan, creator of Breaking Bad, recently said that he thinks Hollywood has been glorifying villains too much and ought to feature more aspirational heroes. I humbly submit Dan Dare as the kind of character we could maybe see more of.

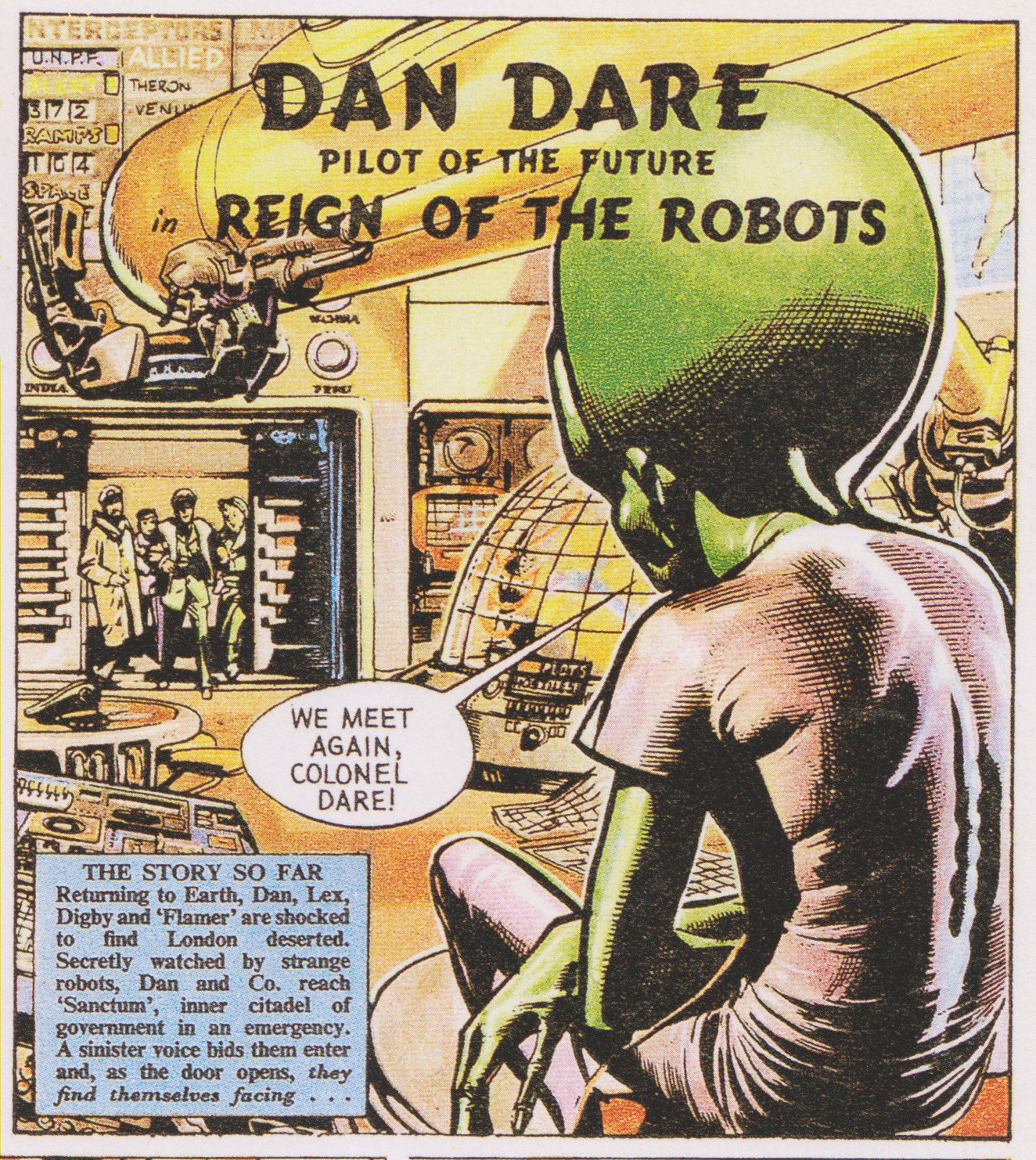

“We Meet Again, Colonel Dare!”

Perhaps more iconic than Dan Dare himself is his arch-enemy, the Mekon, an alien mastermind with a huge head and atrophied body who rides around on a flying chair. When we first encounter him he’s the ruler of the scientifically-minded Treens of northern Venus, and is working on a plan to invade the Earth. He’s deposed at the end of the first story, but returns in roughly every second story with a small band of loyalist Treens and a new plan to conquer the solar system.

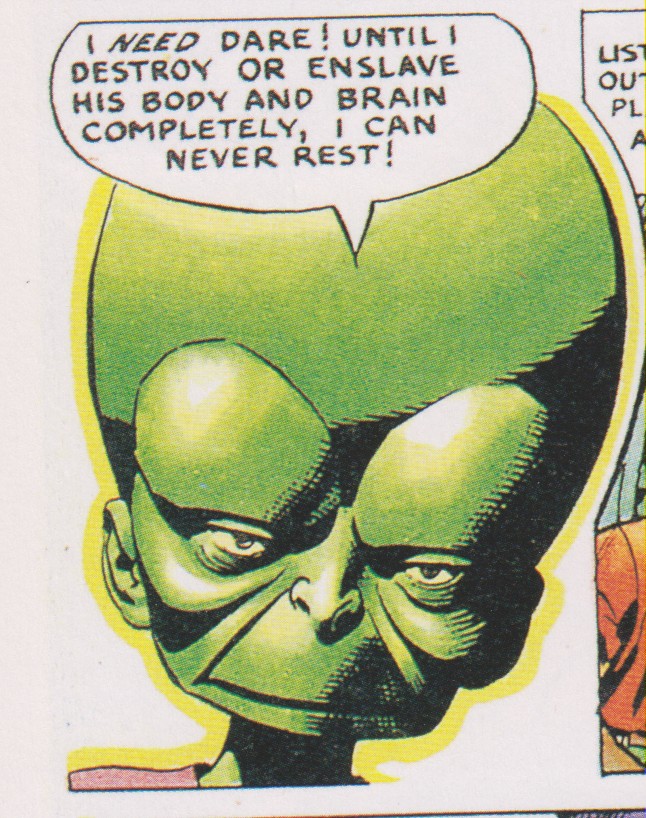

The theme of the Mekon and the Treens is about the dehumanizing effect of science and technology when they’re pursued at the expense of other things. The Mekon is scary because he’s without emotion, and therefore without pity or compassion. He’ll destroy anyone or anything that he doesn’t see as useful for his projects, including his own minions when they fail him.

A Mekon for the Modern Age

Reading the stories in today’s age of unhinged tech-bro billionaires, I can’t help but interpret the Mekon in a different way, one that may or may not have been intended. As the stories progress, the Mekon continues to believe himself to be above primitive human emotions, but he’s increasingly driven by anger, hatred, and a desire for revenge. The real danger represented by the Mekon, as I see it, is not that an overly scientific world-view will turn people into emotionless automatons, but that it will prevent them from understanding the emotions they do in fact still have, so they’ll end up being more driven by destructive emotions rather than less. (Some aliens will literally conquer the whole solar system rather than go to therapy.)

Reading the stories in today’s age of unhinged tech-bro billionaires, I can’t help but interpret the Mekon in a different way, one that may or may not have been intended. As the stories progress, the Mekon continues to believe himself to be above primitive human emotions, but he’s increasingly driven by anger, hatred, and a desire for revenge. The real danger represented by the Mekon, as I see it, is not that an overly scientific world-view will turn people into emotionless automatons, but that it will prevent them from understanding the emotions they do in fact still have, so they’ll end up being more driven by destructive emotions rather than less. (Some aliens will literally conquer the whole solar system rather than go to therapy.)

The villain of my current WIP, Vorak the Master Brain, is my own interpretation of the archetype that the Mekon helped to establish. With Vorak I’m going all-in on the idea of a villain who sees himself as cold and emotionless but is actually a seething pile of anger, ambition, and gleeful cruelty, and who is also not as super-intelligent as he thinks he is. Vorak isn’t the Mekon; Vorak wishes he was the Mekon.

Incidentally, I got the name Vorak by combining the names of two other Dan Dare villains: Vora, the alien dictator in Operation Saturn (who calls himself “The Last of the Great Ones who came from Outer Space,” an intriguing backstory about which nothing else is ever revealed); and Orak, the computer worshipped as a god by the warlike Phants in Rogue Planet.

An Enduring Inspiration

Before Foolish Earth Creatures, none of my own work as a writer and game developer was directly inspired by Dan Dare, but I think it might always have been there as a sort of background inspiration. My ideal heroes are clever, determined, compassionate, and fight for freedom and equality. My villains are entitled bullies—powerful people who want even more power, who believe that they are naturally superior and have a right to impose their will on others. The universe is exciting and colourful and worth learning about; aliens (and, by analogy, anyone who is ‘other’) are people like us and we can benefit from peaceful contact with them. A better world looks more distant than it did in the post-war optimism of the 1950s, but it’s still possible if we work and fight for it.

Maybe that’s weird? But actually, I’m sure a lot of people have some piece of media from their childhood that remains meaningful to them throughout their lives. I’m probably unusual in that mine is from 30 years before I was born, but perhaps that’s something that gives me a unique voice.

Anyway, thanks for sticking with me through this possibly self-indulgent fannish blog post. There’s more I could say about it, but if I do I’ll make some kind of separate Dan Dare fan blog rather than take up space here. If you want to read Dan Dare yourself, I recommend the recent Titan Books reprint series.

There should be a regular dev blog about my new game towards the end of the month.