ARRIVEDERCI PAOLO

14th century map of Villa Zileri in Monteviale Italy

Meaning “farewell’ in English. Paolo was my best friend as a child, and that single word was the last thing I said to him. Early the next morning, my mother and I were driven to a plane, having just learned the night before of my grandfather’s death. We left the Alps on a military flight bound for Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama — a departure from which I would never return.

Except for the past five years, my adult life has been spent in the mountains and wilderness of places like Alberta, British Columbia, Wyoming, and Colorado. I was drawn there because my childhood was at the edge of one of the world’s most beautiful ranges — the Dolomites of northern Italy. In my own American way, I was trying to return home to the mountains as best I could.

All through the years after college I kept a day job. Practicing architecture and planning was simply a way to pay the rent and feed the dog. The real hustle was doing whatever it took to be where I wanted to be — spending every free moment in wilderness. For me, wilderness was medicine for an abusive childhood; long weekends and nights under the stars were an antidote to the poison of trauma.

Months of camping, traveling by canoe through every kind of weather, listening to wolves howl, and living out of a sleeping bag reshaped the way I thought about life. At thirty-four, I realized I had re-kindled the essence of my childhood at the foot of the Alps: the peace of wild places, a wonder at the landscape around me, and the deep belonging that comes from being part of something infinitely larger.

My family had lived in a small community called Monteviale in northern Italy. From our home, you could see a glacier year-round on the edge of the Dolomites, where the Ortles-Cevedale rose 3,905 meters (12,811 feet). I spent endless hours on alpine trails and meadows with childhood friends. The ecology of those mountains and valleys was unlike anywhere else.

Across the street from our home stood a forested hill, encircled by vineyards and a a Renaissance-era villa. Villa Zileri, filled with frescoes and paintings by Giambattista Tiepolo, was a world apart. Within its massive stone walls lay an ancient forest where my friends and I spent countless hours. We played beneath oaks several meters around and sycamores as wide as ten feet — trees that had stood for centuries. This was one of the famed Berici Hills, where the villa, dating back to 1436, rose at the point where vineyards stretched twenty miles toward Vicenza. At its summit stood the chapel of San Francesco, its ceilings adorned with seashells.

It was a world steeped in history, culture, and beauty — which made returning as a teenager to rural Barbour County, Alabama all the more strange. There were no art classes, no mountains, no festivals. Life revolved around Friday night football games, deer hunting, and cruising the town square. I bagged groceries at the Piggly Wiggly, made good friends, but the contrast was stark: instead of concerts, wine fairs, and a hundred days of skiing per year, there was beer in the courthouse parking lot.

I have spent most of the last four decades in this country, with only brief periods of work in the Ukraine and Canada. But now, at fifty-seven, I know rural Alabama is not where I belong. With no family ties left here, I am selling my farm to pursue documentary photography full time. Nearing sixty, I understand it is now or never. After years of saving, living frugally, and paying my entrepreneurial dues, I have earned the right to live my passion.

View from the southeast. Our home was in the right corner

View from the southwest

I credit living beside Villa Zileri with inspiring me to become an architect — a path that eventually led me to photography and later to graduate studies in landscape architecture. The Veneto region, especially northwest of Vicenza, is steeped in beauty, from its rolling hills to the works of Andrea Palladio. Yet the fourteenth-century villa next door to my childhood home was unlike anything else.

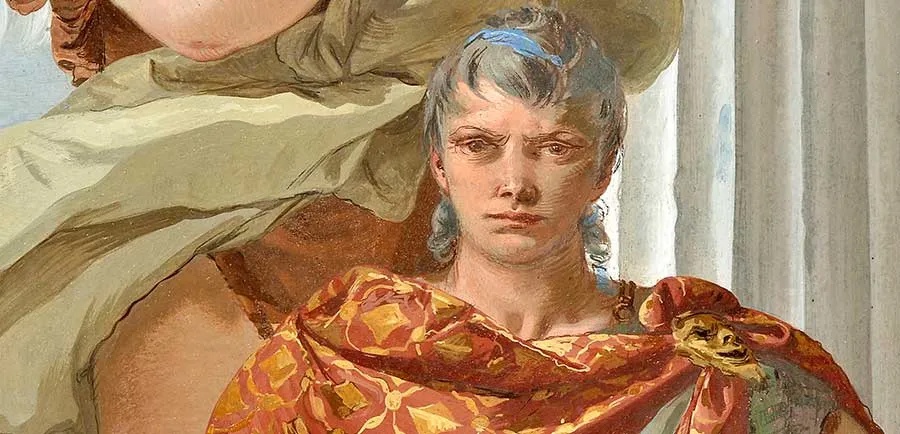

Unlike Palladio’s formal order, the Loschi family chose architects Francesco Muttoni and later Giuseppe Marchi, who designed with a remarkable sensitivity to the land. They allowed the contours of the hills and forests to dictate the placement and proportions of the buildings and interior spaces. After construction, Gianbattista Tiepolo was commissioned to adorn the walls and ceilings with frescoes. The result is nothing short of spectacular.

Interior of Villa Zileri with Tiepolo's frescoes painted on the ceiling and walls

Close-up views of Tiepolo's paintings

In America, architecture too often means strip malls, interstates, and walls that separate the haves from the have-nots. There are no Villa Zileris here — except perhaps behind the gates of enclaves like Palm Beach. To imagine architecture as art is, for most architects, a compromise between passion and the need to pay the bills.

Yet Villa Zileri is not unique in Italy. Across the Veneto region, there is a deep sensitivity to land and craft that shows up even in the smallest side streets. These places have been rich in character for generations. Streets were public spaces where young and old mingled, where retired men gathered to talk. In America, by contrast, such spaces are reserved largely for the wealthy. Why this is so, I cannot fully say. But I know from childhood how deeply the efforts of people like Tiepolo, Muttoni, and Palladio still shape culture centuries later. America certainly has places of beauty, but too often they exist only because wealth allows them — not for the public good. And that privatization of beauty has become a divisive cancer in the culture of the United States.

At Auburn University, where I studied architecture, the late professor Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee often reminded students: “Architecture is not art; its only product is a decaying toxic material you ‘design’ that contaminates soil, killing most microorganisms on the site — erasing whatever habitat was present for countless living beings. You’re a biodiversity serial killer, not an artist. The challenge is to become an artist.” His words stayed with me, though tragically he died before I could complete my thesis.

When the time came, I proposed a year-long study of Villa Zileri and the architectural movement in the Veneto region that shaped it. My assigned thesis advisor dismissed the idea outright: “No one is interested in Italian villas. Everything about that has already been written.” It was my first real taste of a certain kind of arrogance — the belief that America sits atop some evolutionary peak of design, rendering earlier traditions irrelevant. To suggest that a group of fifteenth-century architects, who sought to unite nature and form in ways that inspired Venetian merchants for generations, were unworthy of study was not just short-sighted; it was heart wrenching in the level of ignorance it exposed.

I told her so — in words best left unprinted. That defiance ultimately led me to Jack Williams, who became my thesis advisor. He opened my eyes to the rural South’s urban form and to the role racism played in shaping architecture and planning. It was a perspective I might never have discovered otherwise.

It was one of the rare times in my life where I had to go along to get along — but in the end trusting former Harvard professor Jack Williams, it proved to be in my best interest. That experience taught me never to stop asking questions about the Southern landscape, nor to stop documenting it.

Yet I have never stopped wondering about Muttoni and Marchi’s ideas, or about the little chapel on the hill I once climbed in northern Italy.

One day, I will return to Villa Zileri — this time with camera and sketchbook in hand. And as I begin the next chapter of life, I will look up my old friend Paolo, and finally pursue the thesis I should have written in the first place.

POSTED BY JON B CARROLL