in 1000xRESIST, you're not choosing

OK, so: gamers demand agency, even though they should know full well that they’re at best getting a limited simulacrum of such. games of all types are therefore prone to promising meaningful choices they cannot offer, because a game world is not a world but an interface layer for a sequence of hard-coded rules. (why yes I did just finish reading gameworld interfaces why do you ask)

there are lots of insipid ways this manifests in games (“moral” choices and good-or-bad endings) but I want to focus on dialogue trees.

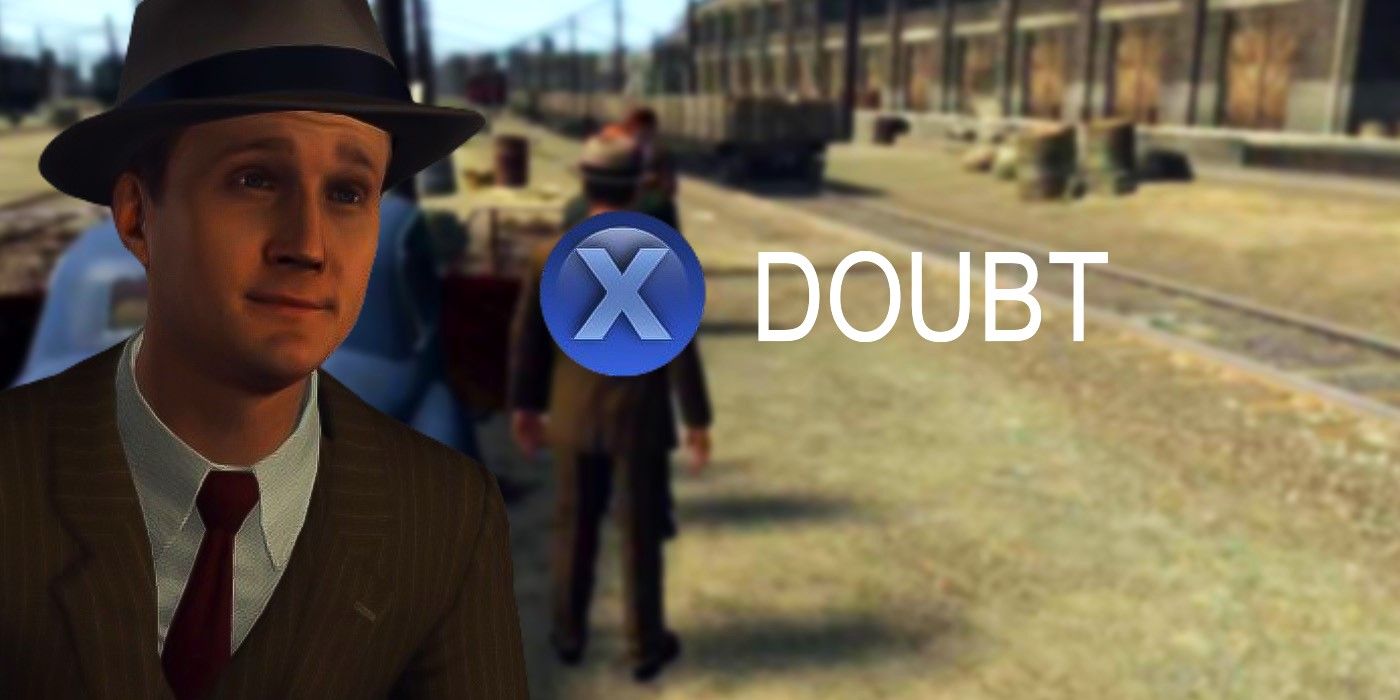

here I’m defining a “dialogue tree” as that part in a conversation between two fictional characters (usually, one of these is your avatar) where everything stops so you can pick from a set of sentences or, like, abstract representations of sentences, the most famous of these spawning the “X to doubt” meme:

dialogue trees can vary from being a core mechanic to a necessary evil to an immense distraction depending on the game genre, but I don’t love them. in RPGs, they are among your best opportunities to express individuality within pre-written systems, but in my experience much more often than not reveal the shallowness of those systems by reducing dialogue to its resultant math. the sense of you-ness is damaged every time a pre-rendered, voice-acted cutscene starts up to remind you that the railroad tracks were placed and routed well before you came along.

plenty of games have value-neutral dialogue trees, too, that don’t have an impact on the game but let you “participate” in a joke or an emotional beat. they’re a reason to pick the controller back up during what would otherwise be “non-play”. (some of the mario games do cute stuff with this. I believe it’s galaxy 2 that has some dialogue trees where your only options are “OK!” and “yep!”)

visual novels can fall into a catch-22 where their entire mode of interaction is dialogue trees, but those options have to all feel like a coherent part of a story that’s being told ostensibly as the accumulation of those branches but which tends to re-converge along pre-written lines, simply because it has no other choice. fledgling manor lets you choose a romance from some of the other contestants, but what you’re really doing is gently steering protagonist rocky in one direction or another. the writing for his character retrofits to your choices, so that they make sense as his; there’s no sense your agency is involved at a level beyond flipping to a given page of a choose-your-own-adventure. (I really liked fledgling manor, by the way! go play it.)

one could say much more about dialogue in video games generally, but I’m going to drill down on one nice counter-example: 1000xRESIST.

(I’m not going to spoil much or get into story, which is going to make this frustratingly vague, but oh well.)

1000xRESIST does not give you “choices” in its trees; instead it splays out the character’s headspace. true variance amongst the offered options is illustratively limited or nonexistent. you’re not allowed to pick a joke response while a character is responding to trauma; you cannot say “no” when your character knows she is going to say yes. sometimes your character is unable to respond, and therefore all you can pick is a line of ellipsis-filled silence.

dialogue trees in 1000xRESIST fall into two camps:

- “ask me questions” lists; it’s usually possible that a particular option will skip your ability to pick the others, but this isn’t always the final option, and otherwise your choices here are as arbitrary as they ever are with this sort of mechanic

- mid-conversational responses

the latter is what I’m interested in, because unlike games that give you “yes” or “no” choices that it has to then retrofit to the story (and usually ignore, long-term, if you pick the path of most resistance to the story being told), the game rarely pretends you’re even choosing anything. instead you’ll get, for example, three options where each option is just “???”, or three fragments in a sequence of the same thought, or two different ways to say “no”.

there are two other variations I can recall where the game inches closer to “choice”, but they’re both illustrative.

one: a couple of times in the late game, as you’re delivering a message to a character, you’re able to choose between “knife” or “no knife” — blunt or tactful, basically. the crucial part is that in each of these moments, choosing either feels valid for the character you’re piloting. the options presented are the kaleidoscope of thoughts running through your POV character’s mind at the moment the dialogue has paused; your selection merely represents the firing of a particular neuron instead of another.

two: there is a puzzle sequence of sorts where you’re meant to match obtuse statements to snippets and sentences you’ve pulled from memories. (that’s going to read weird if you don’t have context; sorry.) here again the game isn’t really letting you “choose” so much as it’s giving you a mechanical demonstration of something it’s about to reveal viz. the way that communication and memory work. your character in these scenes has all this in her mind, which is why she/you are able to choose amongst them; the valid choice only happens when you choose correctly, reflecting both your and the character’s growing understanding. (so, you are at best running alongside the character as portrayed; you are not guiding them.)

this use of interface marries nicely to a lot of the game’s themes — loss of choice or recognition that choice never existed, the fractal variances within infinite repetition, the spirals of internal isolation, the pursuit of truth within the fragmented memory space of human experience. for most of 1000xRESIST’s characters, “choice” is something they’ve never had, born into generational traumas and contexts that shape their ability to perceive the truth at all, much less respond to it with agency.

(OK I lied there will be a mechanical spoiler below)

the final moments of the game have you making an enormous choice about how the world will continue on, but crucially even here the designers put their thumb on the scale. certain choices give you an obvious “bad ending” and crucially don’t run the end credits but just rewind you back to that final moment of choice — suggesting they’re not valid endings at all. you as a player can choose to do a lot of things here, but the character you’re piloting has agency and motivation, and the game understands her well enough to know where her ambivalence lies and thus where the “valid” endings can arise. thus there are only two “good” endings, and their differences are subtle and meaningful (one could even imagine them both taking place in the same thread of reality, to some extent).

really all of 1000xRESIST’s mechanical moves — the linear flight sections, the memory navigation — work along similar lines to this, emphasizing character and drawing out threads of story rather than providing a player with anything even superficially resembling choice or agency. the game understands itself as an interface for its storytelling and leverages this in ways most games don’t or can’t when they struggle with how to pretend to “empower” the player.

better this than games that claim that procgen means you get to make your own story, I think, because 1000xRESIST is a fuckin’ masterpiece.