Jim Morrison, Accidental Icon

After sixty years, Jim Morrison remains rock music’s most problematic and puzzling icon.

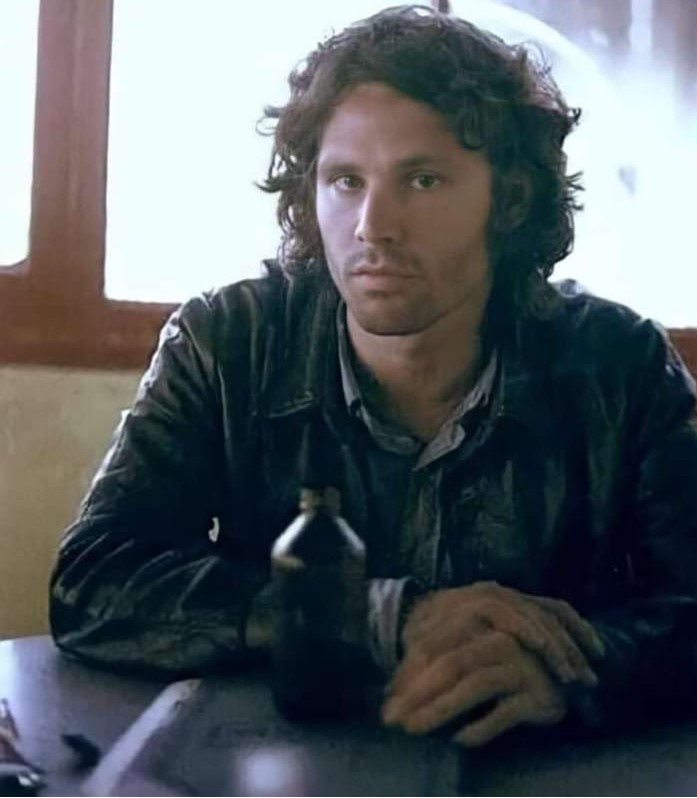

The Doors made spectacular singles in their prime, but that prime was short and they recorded some regrettable songs, too. The best of their music defines the late 1960s in America, but Jim as icon functions visually more than musically. He created the template for the American front man and that sneering attitude of his filters down through every rock-obsessed teenager who has picked up a microphone since.

The infamous 1981 Rolling Stone cover that announced that Morrison was hot, sexy, and dead launched his second life as a GenX myth. That poster of Jim adorning the candlelit wall of the vampire cave in The Lost Boys also reminded everyone that if ever there was a face made for MTV, it was his. Yet we know almost nothing reliable about Morrison and what we do know maps so perfectly onto the cliches of rock stardom that any notion of a real person inside all that hype evaporates.

Thousands of pages of critical analysis have been devoted to Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Bruce Springsteen, Dylan, Led Zeppelin, and The Rolling Stones. For a brief moment, it seemed obvious that Jim Morrison would be included in this rarefied circle. Yet that moment passed in an instant, and now Morrison’s shade dances on the thin wire that separates high and low culture, meaning and nonsense.

By the Way, Which One’s Jim?

Morrison got effusive press reviews at the start of his fame, though within three years he became the butt of the joke, pilloried by hipster journalists for everything from pretentiousness to weight gain. Something about Jim Morrison just tended to piss people off, and his story does not hang together in a coherent way.

Something or someone—and none of the biographers have ever been able to pin this down—seems to have corrupted him at an early age. We still do not know when and why he went so resolutely off-the-rails—was it at 15, in college, or after fame and substance abuse congealed his creative arteries? Most biographical accounts of Morrison focus on alcoholism as a contributing factor to a nervous breakdown that began in 1969. Yet plenty of rock stars were alcoholics; none of them seemed to disintegrate quite so quickly and spectacularly as Jim.

In the otherwise insane book Marilyn: A Biography (1975), Norman Mailer asks an astute question: “Why not assume that Marilyn Monroe opens the entire problem of biography?” The same thing could be asked of Jim Morrison who left virtually nothing tangible behind upon which to construct a convincing account of his life. If you still care about classic rock, which I do, Morrison is always there to be reckoned with, but then again, he isn’t.

He was usually photographed alone, coming across more like a silent-era movie star than a rock star. We never see him being matey with other musicians and rarely see him clubbing. Despite the fact that Morrison apparently hung out at The Factory, and Andy Warhol was a connoisseur of male beauty, the pop artist somehow never got a screen test of Morrison. This is the same Warhol who managed to get Bob Dylan to sit still in front of a camera in 1965 for approximately three whole minutes.

You’re Gonna Fly High

By 1967, Morrison is very famous, with a number one hit on the charts during the Summer of Love and tons of ink being spilled in the mainstream press about his sex appeal. Yet he is curiously absent from the party that every other musician seemed to be attending. The Doors will have no group trips to meet the Maharishi in India, no exile to a French basement to record a masterpiece, no undocumented motorcycle accidents, no rock operas, Altamonts, or Woodstocks.

What little we know about Morrison’s upbringing is frustrating and odd. Perhaps the strangest thing is that Morrison’s father achieved the rank of Rear Admiral in the United States Navy and was purportedly involved in the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964, which galvanized President Johnson’s massive escalation of the Vietnam War. His son soon becomes one of the most famous faces of the so-called Youth Quake in America, yet almost no one comments on this incongruity.

If someone had found out in 1967 that any other rock star’s dad or uncle was a major player in the Gulf of Tonkin incident, this presumably would have rated at least a paragraph or two in the music press, possibly ejection from the circle of cool. Yet even as the Vietnam War boils over, Morrison lands in Los Angeles fully formed and exquisitely thin, prefabricated for stardom, sporting a fabulous Jay Sebring haircut and no problematic backstory.

From here, weird things start to accumulate. Check out the three-minute video for Light My Fire floating around on YouTube, not the one from the Ed Sullivan Show but an obscure clip that looks like it was pieced together by a drunken intern. As Robby, Ray, and John jam on a fire truck, we see footage of burning houses alternating with images of California girls with California smiles. It is loopy and very 1960s, like a carnival ride about to go off the rails.

What really ratchets up is the weirdness is that the man dancing with his back to the camera is obviously a stand-in and looks ridiculous weaving about madly with his feet planted firmly to the ground. When the real Morrison finally appears, he is not filmed with his bandmates but in close-up shots randomly dropped into the song. This artifact of a pre-MTV age looks like a publicity video that was assembled after the money men decided who passed the audition for a Doors lead singer. If so, that would put paid to the “I met Jim on a beach” myth that Manzarek peddled for years and put the band’s origins more in line with The Monkees.

Morrison and the people around him also seem like stick figures rather than real people. Comparing Jim Morrison to Janis Joplin brings his strangeness into relief. Despite her equally short life, Janis Joplin left behind a rich biography. The Janis Joplin timeline checks out, and her reactions and decisions follow plausibly from the events of her life. We see her surrounded by managers, bandmates, romantic partners, and family members. We know that she hated Port Arthur, Texas, where she grew up, and we watch as her bravado at her tenth high school reunion quickly dissolves into tears. Even at a distance, Janis Joplin seems like a real person. Jim Morrison does not.

You’re Too Cool to Fool

Jim Morrison always brings the critic or biographer to a cul-de-sac: either he was remarkably good at maintaining privacy despite his fame or he was as constructed a figure as the mythical Lee Harvey Oswald of Oliver Stone’s fever dreams. That doesn’t necessarily lessen his impact or the brilliance of the band’s best songs. But it does raise questions about the degree to which the myths of the 1960s were constructed in real-time and burnished to a high gloss as America slid into the 1980s.

Was Jim Morrison, as Stephen Davis contends, “the true avatar of his age,” which implies that if we understood Jim Morrison we would finally understand the 1960s. Or was he Lester Bangs’ “Bozo Prince,” a man with great cheekbones and middling talent who drowned whatever potential he may have had in a noxious stew of arrogance, chronic drug abuse, and willful psychopathology?

The key to making sense of Morrison is to give up on any attempt to weave these wayward fragments of biography into a plausible life. Despite the elusiveness of the real person, buried now under layers of media sediment, hype, and fabrications, Morrison made punk rock possible, just as he made the gender-bending antics of David Bowie, Iggy Pop and T-Rex possible. Rock Star wasn’t a cliché when he did it, because he did it first.

His persona was neither gay nor camp, and he didn’t live long enough for the “are they or aren’t they” posturing of glam rock. Yet the top-to-toe black leather uniform that Morrison wore on the Ed Sullivan show was not mainstream Beach Boys/fraternity house heterosexual either. The Warhol crowd liked to claim that Morrison stole the leather look from Gerard Malanga, but no matter. Even if that is true, taking the look above ground was a far riskier thing to do in 1967.

Elvis Presley dropped into our mass culture with such ferocious force that he had to be drafted and then spit back out of the Army to enact a sanitized version of himself for Hollywood and Las Vegas. Jim, who could have been Elvis’s middle-class cousin, the one with a dad in the professional military, a better education and nicer house, also got his moment on the Ed Sullivan Show. In his case it took less than five years in the American spotlight, compared to twenty for Elvis, for this strange young man to disintegrate.

Even in that short span of time, there were at least three Jims: Rock Star Jim, Poet Jim, and Jimbo the Alcoholic, and maybe even a fourth, Posthumous Jim, who flew out of the story as mysteriously as he had flown into it five years earlier. At this stage, we will probably never know who Jim Morrison really was. Nevertheless, the 1960s in America would be less interesting without him.

Indeed, had Jim Morrison not existed, we would have had to invent him.