Looking (Again) at Linda Lovelace

Linda Lovelace (nee Boreman) cycled through so many personas in her short life that it is difficult to place her in the pop culture landscape.

Is she the effervescent star of the adult movie Deep Throat (1972), ushering in a new era of sexual liberation and porn chic? Or is she the damaged and abused woman who narrates Ordeal (1980), the third memoir published under her assumed name? Perhaps she is the human equivalent of the pet rock, a highly profitable (though not for her) spasm of pop silliness that worked for a nanosecond but is inexplicable now.

Something about this woman and her story does not track. She comes across as naïve, victimized, cynical, sincere, cloying, pathetic, and brave, often in the space of just a few short quotes. Testimony from colleagues who were with her on movie sets or who knew her husband, porn impresario Chuck Traynor, only further complicates things. Half of them seem to believe she was a victim of sustained abuse while others dismiss her as a practiced liar.

For all that—maybe because of that—I think she still matters. If I am asked to take Hugh Hefner seriously, as the documentary Secrets of the Playboy Mansion plausibly does, then Linda Lovelace merits attention, as well. Her once bright then strained smile flashes like a neon sign above the pornified world we live in today.

Deep Throat and Porn Chic

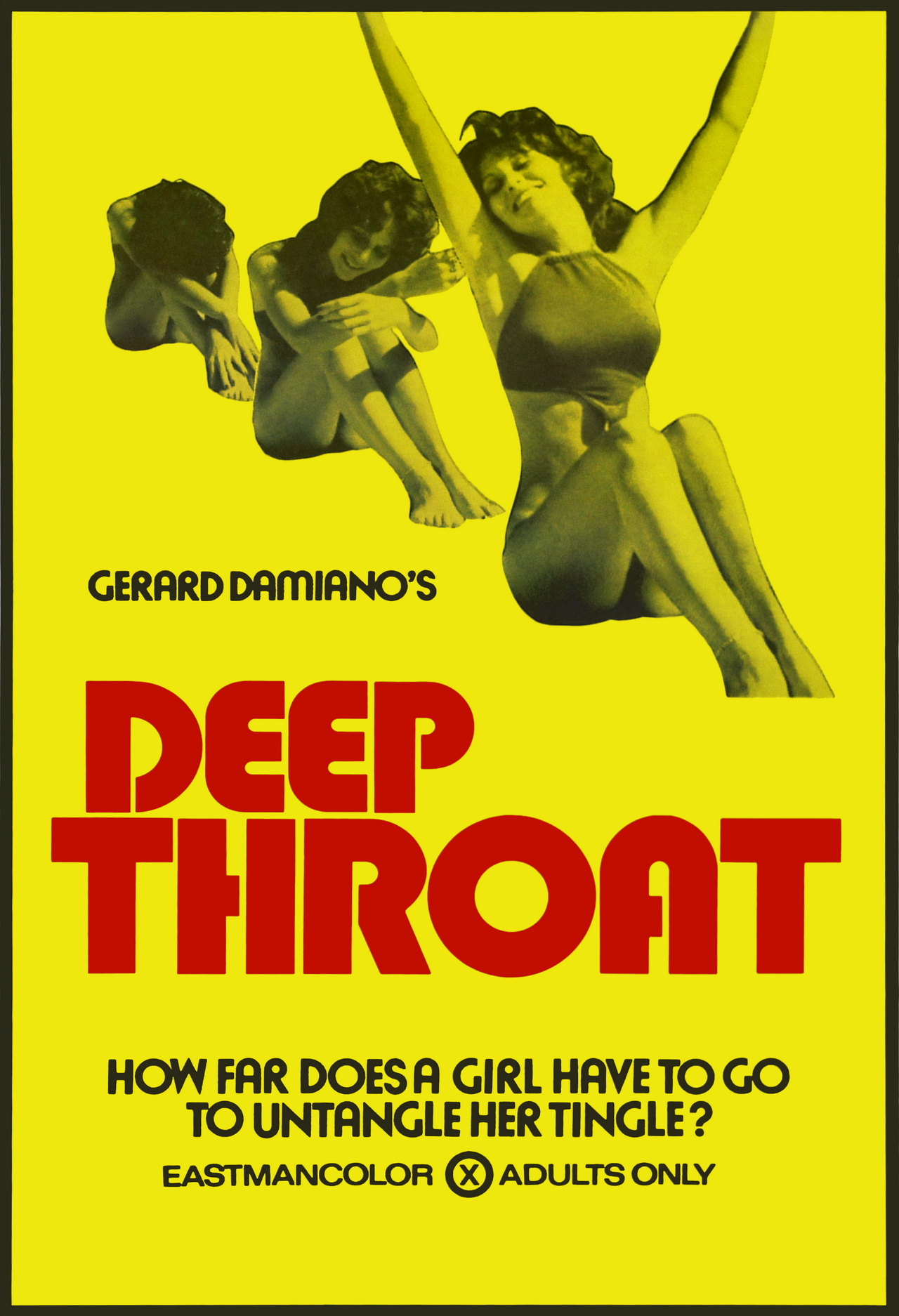

Premiering in Times Square on June 12, 1972, this silly and implausible movie bottled lightning by centering on a female character at the exact moment second-wave feminism broke through the cultural gates. The original poster zings with 1970s energy, from the “have a nice day” yellow background to the photo of Linda looking slim, happy, and satisfied. (It is a subject for another blog, but 1970s thin people were thin in a way that even thin people are not, anymore).

Though the fantasies the movie prioritized were still decidedly heterosexual male, phrases such as the “girl next door” and “nice girls like sex, too” repeated on a loop as feminists, critics, comedians, and even The New York Times propelled the movie to a top 10 box-office hit. Most scholars today estimate that the film has grossed at least $600 million worldwide, on an initial budget of approximately $30,000. It is credited with bringing adult movies to the mainstream and scaffolding the Golden Era of Porn.

Linda Lovelace always admitted that she enjoyed her moment of fame. The movie launched her onto talk shows and to parties at the Playboy Mansion, placing her among a richer and seemingly more refined class of people (however ersatz) than those she had known on the stag film circuit. Her fluttery charm worked well on television, and she seemed to be in on the joke.

From Inside Linda Lovelace to Ordeal

The shift from the let-it-all-hang-out 1970s to the buttoned-down 1980s happened so fast that it is no wonder Linda Lovelace got whiplash. Everyone did. Part of this had to do with a resurgent conservative movement that loathed almost everything that happened after The Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan. When the first news article on the AIDs crisis appeared in The New York Times on July 3, 1981, you could almost hear the spinning mirrored disco balls grind to a halt overnight.

Yet the most important change for Lovelace may have been the way in which second wave feminism started to fragment into different strands, with sex-positive feminists like Camille Paglia pitted against anti-porn advocates such as Andrea Dworkin in the media. Much of America sat back and watched as feminism tore itself apart in the 1980s but Linda Lovelace stepped right into the fray.

I confess that when I first read Ordeal, my skepticism meter was running hot, even though I knew the publisher had required Lovelace to take a lie detector test before releasing the book. This wasn’t a Rashomon-style kaleidoscope of differing perspectives as it was a complete refutation of everything that had gone before. The Lovelace in these pages is victimized repeatedly and brutally, and is the brunt of the joke, never its author.

Lovelace ultimately testified before a Congressional committee investigating the porn industry in the 1980s that anyone who watched Deep Throat was watching her being raped. This statement, from the woman who embodied the sexual revolution, who had been bubbly and so much fun on the talk show circuit, caused the public to recoil. This was not a story that anyone really wanted to hear. Even Phil Donahue seemed to barely contain his contempt when she appeared on his show.

Looking at Linda Lovelace Today

I have no idea if Linda Lovelace was or was not telling the whole truth in Ordeal, whether she enjoyed any of her scenes in Deep Throat, or if Chuck Traynor’s second marriage to porn star Marilyn Chambers was a happy one (implying that it was Linda who was the problem all along). I can easily believe that both Gloria Steinem and Andrea Dworkin genuinely liked Lovelace but also knew a useful cautionary tale when they read one.

Cultural divides as fraught as the one between the 1970s and the 1980s arrange stories along neat grids: in this case, either Linda Lovelace lied about her razzle-dazzle heyday, or she lied about being a victim of abuse and sexual trafficking. The parallel tracks of her story in these decades do not converge at any point, so we never quite know where we stand with her.

Yet perhaps we can look at this story another way, focusing less on the truth-of-the-matter and more on the culture that this hapless woman was trying to negotiate. Linda Lovelace might seem naïve, victimized, cynical, sincere, cloying, pathetic, and brave, but mostly she seems damaged. Here we have a neglected child from the lowest rung of the midcentury middle class, who grew up in an atmosphere of abuse juxtaposed with dreams of marriage and white picket fences. The first legal case of a man prosecuted for raping his wife will not take place until 1978 (Oregon v. Rideout), a full ten years after Linda meets Chuck Traynor. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) will not be added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual until 1980.

Linda Lovelace grew up in a world where concepts we take for granted had not yet been thought. This does not mean everyone gets a free pass, but it does mean that putting a 2025 lens on the early 1970s should be done with care. In her early 20s, she appears in a movie that even the director predicted would flame-out in a few days like virtually every other “dirty movie” before it but instead catapults her to Hollywood and The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. The girl raised to please others above all other considerations is in the spotlight, is welcomed, is a star. In these strange circumstances, Linda Lovelace could have readily embraced the fact of starring in Deep Throat without having liked making it, at all.

Still Stuck in the 1970s

Millions of people enjoyed the sexual revolution when it happened. Linda Lovelace was among the unlucky who were saddled with an indelible record of every single good and bad choice they made in those few frothy years. She also went broke and slid right back down the class ladder. There was no one to protect her, not even Chuck Traynor.

Jack Nicholson, Roman Polanski, Frank Sinatra, and Sammy Davis, Jr., among many others who enthusiastically embraced the porn chic culture of the 1970s, got to live full lives for four more decades. They were far more talented, no doubt, but on a human level that is not really the point, especially in the post #MeToo era. The point is they got to leave the 1970s behind. Linda Lovelace never did.

This is probably the main reason I think she matters today. Deep Throat may have been one of the first professional porn films, but Linda Lovelace was the ultimate amateur. And according to Pornhub, which keeps meticulous track of data on the adult industry, searches for “real amateur homemade” porn in 2022 grew by 310 percent in the United States and 169 percent worldwide.

So, when I do think about Linda Lovelace, I can’t help but wonder how many of these 19-year-old women may find themselves looking at things differently in, say, 2045, while all those early choices continue to circulate on a loop in digital space.