Ghost in the scan — 3D scans of casts in the SMK’s collections

“What kind of ghost continues to haunt the scanned 3D model of the sculpture?” — paraphrased from a conversation with the artist-hacktivists Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, who scanned and released a 3D model of the Nefertiti bust at Neues Museum in Berlin in December 2015

View of the digital inside of the Discobulus made with the digital cast. Screenshot by artist Honza Hoeck, courtesy of the artist.

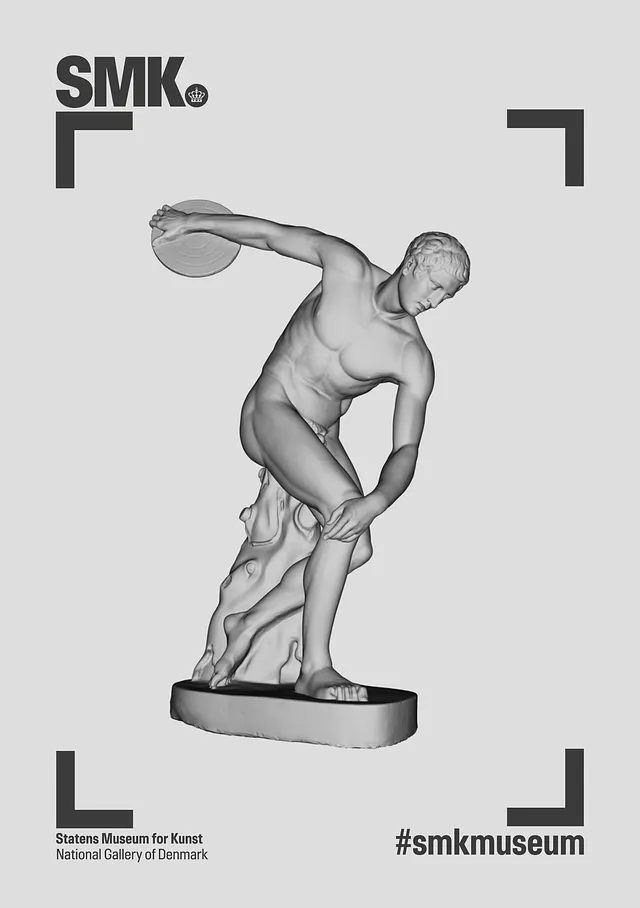

For sixteen months now I have had a 1:10 scale 3D plaster print of the Discobolus (approximately 450 BCE) posing on my desk. Being printed in plaster, it feels cool and heavy when handled. Close inspection reveals the layers and pixels of the printing process. It is simultaneously obviously digital and an attractive physical object.

Discobolus (approximately 450 BCE) scanned and printed in plaster in scale 1:10 .

A former colleague had invited the Danish company 3D Printhuset to demonstrate their 3D scanning and printing technology after having noticed them at a tech fair. It took us a long time to decide how to test the potential of 3D technology in the museum context. The technology has a range of potential applications within the realms of research, conservation and interpretation & learning. We chose to begin by focusing on the latter field: How our users engage with the art.

The result was the pilot project Digital Casts, funded by the Bikuben Foundation as part of the SMK² series. SMK² is the common heading used for a range to experiments where SMK invites artists, writers and other professions to engage with the museum collections in new ways in order to give museum users new and surprising art experiences — and this project certainly offered great scope for new and surprising art experiences.

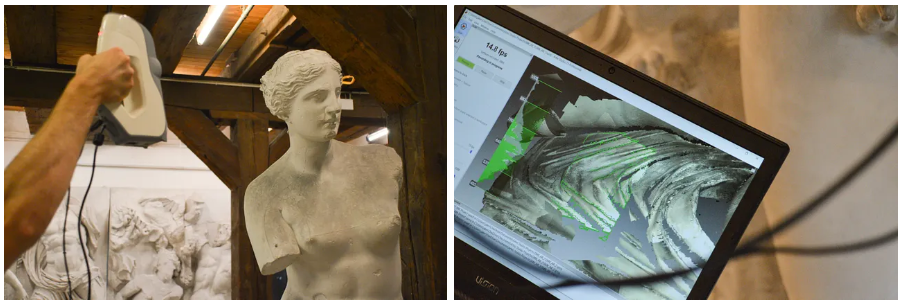

From the scanning proces at the Royal Cast Collection. Photos by Magnus Kaslov

From the scanning proces at the Royal Cast Collection. Photos by Magnus Kaslov

Stepping from 2D to 3D

Digital Casts explores how the museum can take the next step in terms of what it makes available to the public: from two-dimensional reproductions in the form of digital image files of paintings, drawings and prints to three-dimensional reproductions in the form of 3D models of sculptures.

In recent years SMK has made great headway in its efforts to release the rights to images of works from the SMK collections, and the museum has also begun making high-resolution images available in the public domain. The pace and scope of this work will accelerate in the years to come under the auspices of the SMK Open project, which is funded by the Nordea Foundation.

Six masterpieces — and an unknown head

Scanning sculptures from The Royal Cast Collection was a natural choice: partly because there are no copyright issues associated with these sculptures, meaning that the museum is free to release reproductions without first obtaining consent from the artists or their estates/heirs. But also partly because the fame and already extensive history of reproduction means that these iconic casts have taken on a life of their own, one that is not as closely associated with specific authorship as more recent works would be. In other words, it was easier to scan these casts without feeling that we moved in on the rights or legacy of a specific artist. There was also a simple logic behind the decision to scan and digitally reproduce casts that were in fact reproductions to begin with. With casts you are already in the realm of copies.

We eventually scanned seven plaster casts from The Royal Cast Collection, making them available as digital high-resolution 3D models. The 3D models of the seven sculptures have been released under Public Domain licences, meaning that anyone is free to share them, use them, reshape them, animate them, 3D print them — anything at all. Six of the casts were selected by curator Henrik Holm in order to reflect, as far as this was possible, the breadth of the cast collection and the canon and art historical narrative it represents.

In addition to six iconic sculptures from classical European art history the project also features a seventh 3D model. In co-operation with Living Archives Research Project at Institutionen för Konst, Kultur och Kommunikation at the University of Malmö, SMK also released a 3D model of the bust Memnon of Ethiopia, which shows the head of an unknown man of African descent who sat for this portrayal of the mythological king. The Living Archives contribution means that the project includes a non-iconic, relatively unknown sculpture, thereby pointing to some of the problems inherent in the Eurocentric art canon that the Royal Collection of Plaster Cast is modelled on — and which the other six 3D models reflect.

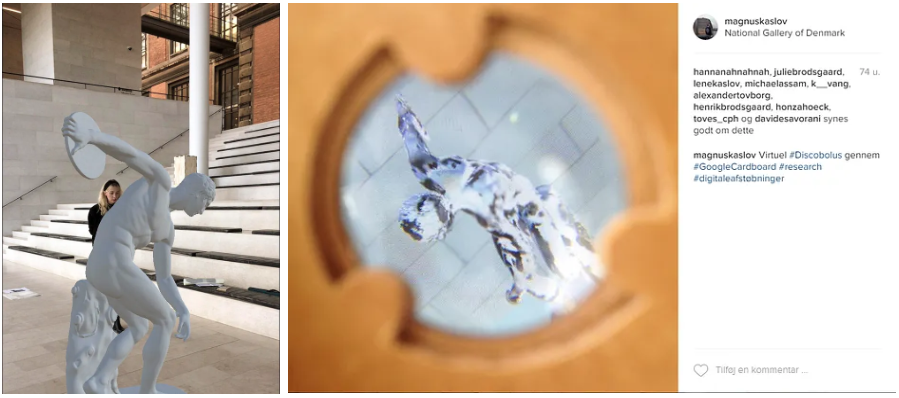

Testing the digital casts in augmented reality. On the left an test at the SMK with digital producer at SMK Rine Rodin and on the right a screenshot from Instagram of an early test with virtuality and Google Cardboard. Photos by Magnus

Testing the digital casts in augmented reality. On the left an test at the SMK with digital producer at SMK Rine Rodin and on the right a screenshot from Instagram of an early test with virtuality and Google Cardboard. Photos by Magnus

Free to use for Augmented Reality — and anything at all

Our collaboration with Living Archives arose out of the idea to present the digital casts as Augmented Reality features at the launch. This was done partly in order to anchor the experience of the digital 3D models in a physical reality, and partly to point to some of the many ways in which the models can be used. The public domain licence means that they can be used for anything at all: 3D printing at home, commercial computer games, raw materials for new works of art — absolutely anything.

We ended up creating our AR experience in collaboration with a local software developer, Michael Hansen, but nevertheless we met with Living Archives, and our conversation with professor Susan Kozel and PhD Temitope Odumosu gave rise to the idea of challenging the selection criteria behind the six sculptures we intended to scan. The addition of a seventh sculpture is a simple, yet powerful approach that points towards the more or less hidden issues of power and exchange that are embedded in the Cast Collection, and which the Digital Casts project will inevitably reproduce.

Guests looking at the digital casts in augmented reality at the launch of the project at the event SMK Fridays on november 11 2016. Photos by Jonas Heide Smith.

Guests looking at the digital casts in augmented reality at the launch of the project at the event SMK Fridays on november 11 2016. Photos by Jonas Heide Smith.

Making art findable

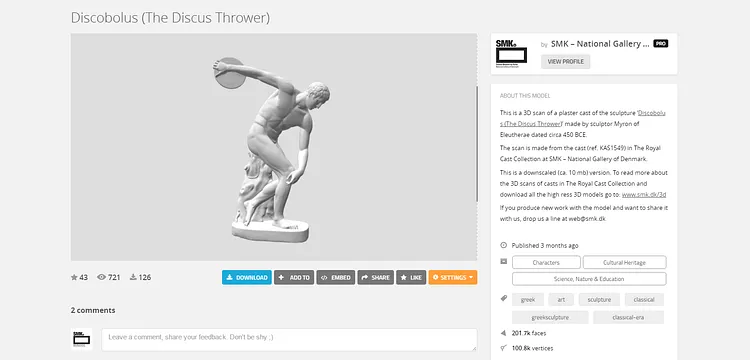

The key objective of the Digital Casts project is to make the 3D models available to everybody. Of course, this involves more than simply putting a download link up at smk.dk. We have to make them visible and easy to find — thereby facilitating use in various private, artistic and commercial contexts. As yet, we have presented the project to the world in a range of ways: partly via our own media and at the launch event, and partly by pushing the 3D models away from our own platforms, uploading them to platforms where animators, home printers and 3D professionals usually use. As yet, the sculptures are available for download and unrestricted use at Sketchfab, Thingiverse and TurboSquid.

After the launch we also held two workshops in co-operation with the artist Fredrik Tydén. Here, participants could work with the 3D models on the basis of input from the SMK team and from Tydén. The two workshops proved overwhelmingly popular, attracting art academy students, animators, graphic designers and hobby enthusiasts.

Workshop at the Royal Cast Collection. Art academy students, animators, graphic designers and hobby enthusiasts joined curator of the Cast Collection Henrik Holm, digital producer Rine Rodin and myself for two half day workshops. Photos by Magnus Kaslov

Workshop at the Royal Cast Collection. Art academy students, animators, graphic designers and hobby enthusiasts joined curator of the Cast Collection Henrik Holm, digital producer Rine Rodin and myself for two half day workshops. Photos by Magnus Kaslov

New engagement in the art works

First and foremost, the project makes high-quality data easily accessible to all. Compared to the fifteen other versions of the Venus de Milo available on Turbosquid at prices of up to USD 150, the SMK scan offers far better detailing and realism. This clearly points to the need for careful quality assurance measures, for the SMK scans will be perceived as authoritative versions that bear the museum’s stamp of approval — which, of course, they are.

Now that a few months have gone by after we first released the 3D models, we can look back on a time of considerable attention from traditional media such as TV and online art media, but also of extensive interaction with individual users and artists who use the models. For example, I have corresponded with an American user on Thingiverse, Jerry Fisher, concerning the unadulterated, unmodified appearance typical of our scan of the Venus de Milo. He greatly appreciated the fact that to his mind, the scan was more faithful to how the sculpture looked when it was originally found (in several pieces) than the original sculpture now displayed at the Louvre in Paris.

Jerry Fisher says: “I’ve devoured everything I could find about the Aphrodite of Milos. I read much about particular details and features of the original. It was difficult to completely understand the importance of features like the wear patterns on parts of the surface which gave clues about the conditions the statue probably was displayed in. Now with your scan, I can actually see the features that were considered important to artists, historians and archaeologists in the past.”

Get a closer look at the Discobolus’ digital cast here in Sketchfab by turning and zooming the virtual model.

What ghost lingers on in the 3D model?

To return to the quote presented in my introduction, it should be noted that Digital Casts offers a new perspective of one of the key subjects of art and art history: the power of attraction that images exert. The fact that reproductions almost magically retain some of the aura — or ghost, or value, or meaning, or whatever you wish to call it — of what they represent. What the art historian David Freedberg calls ”the power of images” in his by now classic book bearing the same title.

Images speak to us, and we want to speak to them. This also holds true of three-dimensional images. We like to surround ourselves with them and to possess them. 3D scans retain some of the traits that fascinate us about the original sculptures. I cannot say exactly what that is, but something very clearly lingers. This trait is not only useful for those who present art — it also adds poignancy to the subsequent existence of these 3D models as they are put to various uses.

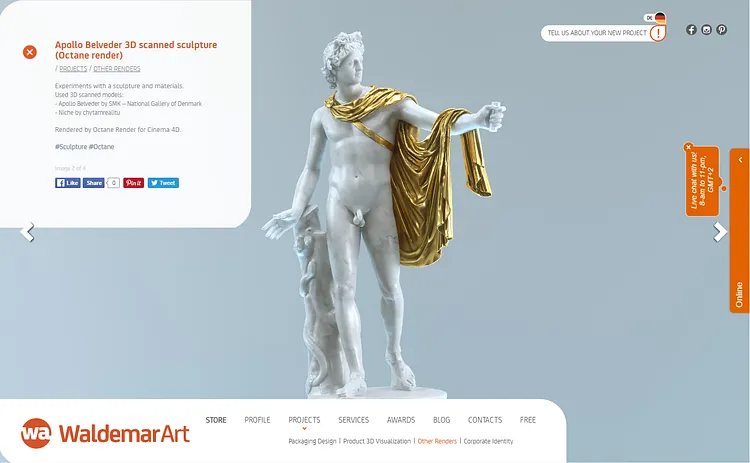

A screenshot of the user Waldemar Art‘s creation using one of the digital casts.

Plaster casts and spiritual meaning

In 1872 Julius Lange, who later became the first director of the Royal Cast Collection, argued in favor of arranging a cast collection at the Royal Art Academy in at art historically scientific manner: “a complete collection of paster casts covering sculptural works from the classical epochs, arranged by an understandable and educational scientific principle, is of far more use in search for knowledge in art than a collection of precious masterpieces.” He didn’t contest that the originals also had their merits which he called sentimental value, the same as the relic had ahead of the cast, but that did not bear on the artistic value. Marble and bronze were beautiful materials, yet the plaster in full reproduced the plastic shape: “from where the work of art gets its spiritual meaning”. (translated from danish in Villads Villadsens book on the National Gallery: Statens Museum for Kunst 1827–1952, my emphases)

— — —

To find and download all the 3D models and metadata go to smk.dk/3d or find them on Sketchfab, Thingiverse or TurboSquid.