Canadian Sovereign Threat Exercise: Windows 11 (further options)

Scenario Overview

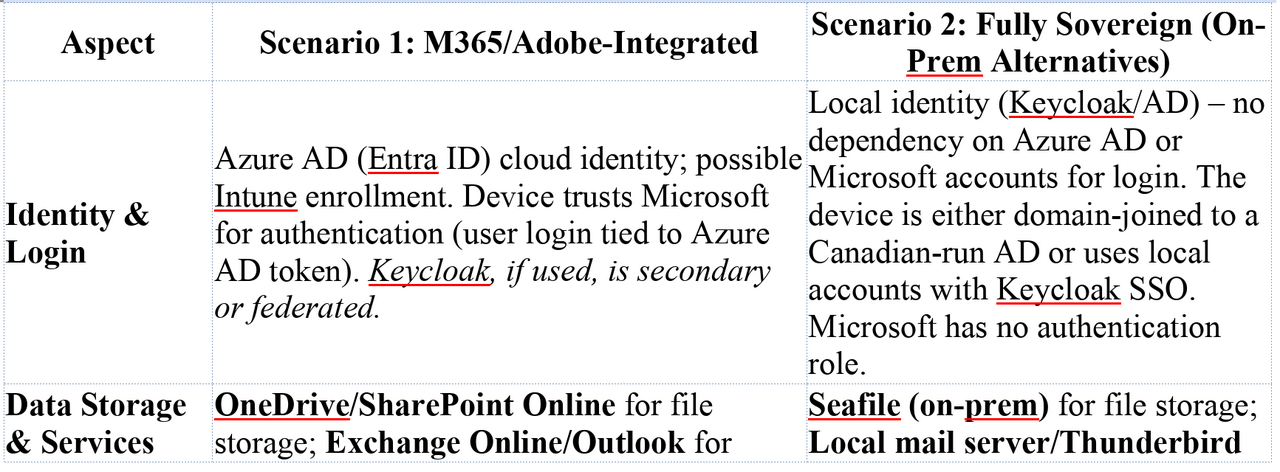

Microsoft 365-Integrated Workstation (Scenario 1): A Windows 11 Enterprise device fully integrated with Microsoft’s cloud ecosystem. The machine is joined to Microsoft Entra ID (formerly Azure AD) for identity and possibly enrolled in Microsoft Intune for device management. The user leverages Office 365 services extensively: their files reside in OneDrive and SharePoint Online, email is through Exchange Online (Outlook), and collaboration via Teams is assumed. They also use Adobe Acrobat with an Adobe cloud account for PDF services. The device’s telemetry settings are largely default – perhaps nominally curtailed via Group Policy or a tool like O&O ShutUp10++, but Windows still maintains some level of background diagnostic reporting. System updates are retrieved directly from Windows Update (Microsoft’s servers), and Office/Adobe apps update via their respective cloud services. BitLocker full-disk encryption is enabled; since the device is Entra ID-joined, the recovery key is automatically escrowed to Azure AD unless proactively disabled, meaning Microsoft holds a copy of the decryption keyblog.elcomsoft.com. All in all, in Scenario 1 the user’s identity, data, and device management are entwined with U.S.-based providers (Microsoft and Adobe). This provides convenience and seamless integration, but also means those providers have a trusted foothold in the environment.

Fully Sovereign Workstation (Scenario 2): A Windows 11 Enterprise device configured for data sovereignty on Canadian soil, minimizing reliance on foreign services. There is no Azure AD/AAD usage – instead, user authentication is through a local Keycloak Identity and Access Management system (e.g. the user logs into Windows via Keycloak or an on-prem AD federated with Keycloak), ensuring credentials and identity data stay internal. Cloud services are replaced with self-hosted equivalents: Seafile (hosted in a Canadian datacenter) provides file syncing in lieu of OneDrive/SharePoint, OnlyOffice (self-hosted) or similar enables web-based document editing internally, and Xodo or another PDF tool is used locally without any Adobe cloud connection. Email is handled by an on-prem mail server (e.g. a Linux-based Postfix/Dovecot with webmail) or via a client like Thunderbird, rather than Exchange Online. The device is managed using open-source, self-hosted tools: for example, Tactical RMM (remote monitoring & management) and Wazuh (security monitoring/EDR) are deployed on Canadian servers under the organization’s control. All Windows telemetry is disabled via group policies and firewall/DNS blocks – diagnostic data, Windows Error Reporting, Bing search integration, etc., are turned off, and known telemetry endpoints are blackholed. The workstation does not automatically reach out to Microsoft for updates; instead, updates are delivered manually or via an internal WSUS/update repository after being vetted. BitLocker disk encryption is used but recovery keys are stored only on local servers (e.g. in an on-prem Active Directory or Keycloak vault), never sent to Microsoft. In short, Scenario 2 retains the base OS (Windows) but wraps it in a bubble of sovereign infrastructure – Microsoft’s cloud is kept at arm’s length, and the device does not trust or rely on any U.S.-controlled cloud services for its regular operation.

Telemetry, Update Channels, and Vendor Control

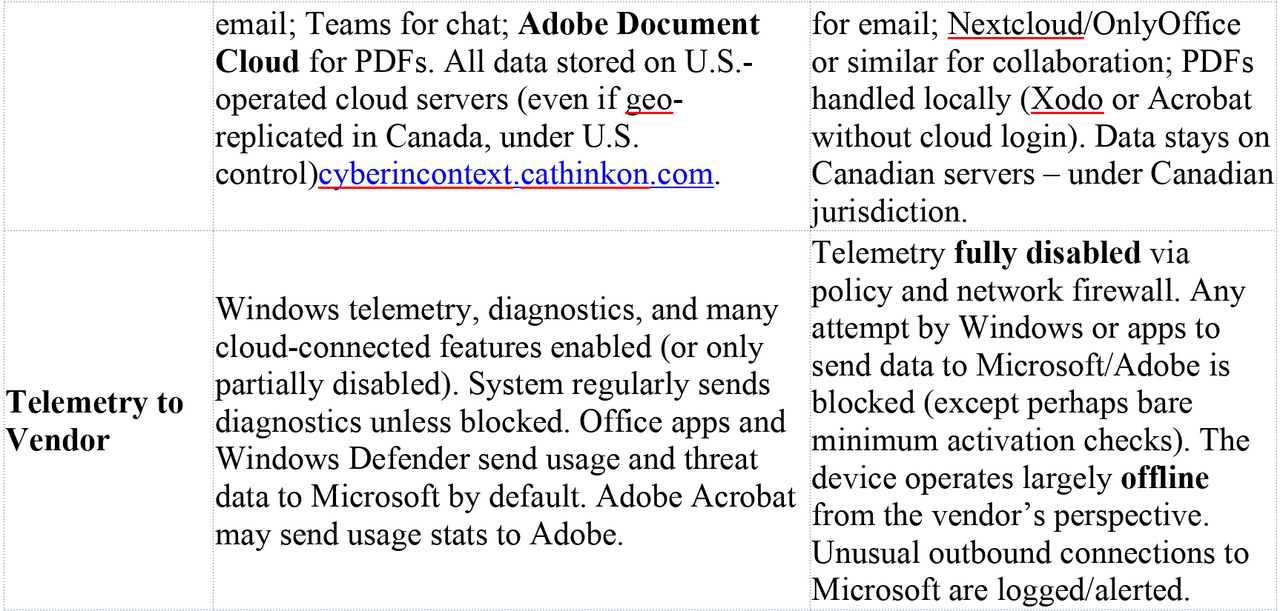

Microsoft-Facing Telemetry & Cloud Services (Scenario 1): By default, a Windows 11 Enterprise machine in this scenario will communicate regularly with Microsoft and other third-party clouds. Unless aggressively curtailed, Windows telemetry sends diagnostic and usage data to Microsoft’s servers. This can include device hardware info, performance metrics, app usage data, reliability and crash reports, and more. Even if an admin uses Group Policy or tools like O&O ShutUp10 to reduce telemetry (for instance, setting it to “Security” level), the OS sometimes re-enables certain diagnostic components after updatesborncity.comborncity.com. Built-in features like Windows Error Reporting (WER) may upload crash dumps to Microsoft when applications crash. Many Windows components also reach out to cloud services by design – for example, Windows Search might query Bing, the Start Menu may fetch online content, and SmartScreen filters (and Windows Defender cloud protection) check URLs and file signatures against Microsoft’s cloud. In an Office 365-integrated setup, Office applications and services add another layer of telemetry. Office apps often send usage data and telemetry to Microsoft (unless an organization explicitly disables “connected experiences”). The user’s OneDrive client runs in the background, continuously syncing files to Microsoft’s cloud. Outlook is in constant contact with Exchange Online. If the user is logged into the Adobe Acrobat DC app with an Adobe ID, Acrobat may synchronize documents to Adobe’s Document Cloud and send Adobe usage analytics. Furthermore, because the device is Entra ID-joined and possibly Intune-managed, it maintains an Entra ID/Intune heartbeat: it will periodically check in with Intune’s cloud endpoint for policy updates or app deployments, and listen for push notifications (on Windows, Intune typically uses the Windows Notification Services for alerts to sync). Windows Update and Microsoft Store are another significant channel – the system frequently contacts Microsoft’s update servers to download OS patches, driver updates, and application updates (for any Store apps or Edge browser updates). All of these sanctioned communications mean the device has numerous background connections to vendor servers, any of which could serve as an access vector if leveraged maliciously by those vendors. In short, Microsoft (and Adobe) have ample “touchpoints” into the system: telemetry pipelines, cloud storage sync, update delivery, and device management channels are all potential conduits for data exfiltration or command execution in Scenario 1 if those vendors cooperated under legal pressure.

Key surfaces in Scenario 1 that are theoretically exploitable by Microsoft/Adobe or their partners (with lawful authority) include:

- Diagnostic Data & Crash Reports: If not fully disabled, Windows and Office will send crash dumps and telemetry to Microsoft. These could reveal running software, versions, and even snippets of content in memory. A crash dump of, say, a document editor might inadvertently contain portions of a document. Microsoft’s policies state that diagnostic data can include device configuration, app usage, and in some cases snippets of content for crash analysis – all uploaded to Microsoft’s servers. Even with telemetry toned down, critical events (like a Blue Screen) often still phone home. These channels are intended for support and improvement, but in a red-team scenario, a state actor could use them to glean environment details or even attempt to trigger a crash in a sensitive app to generate a report for collection (this is speculative, but exemplifies the potential of vendor diagnostics as an intel channel). Notably, antivirus telemetry is another avenue: Windows Defender by default will automatically submit suspicious files to Microsoft for analysis. Under coercion, Microsoft could flag specific documents or data on the disk as “suspicious” so that Defender uploads them quietly (more on this later).

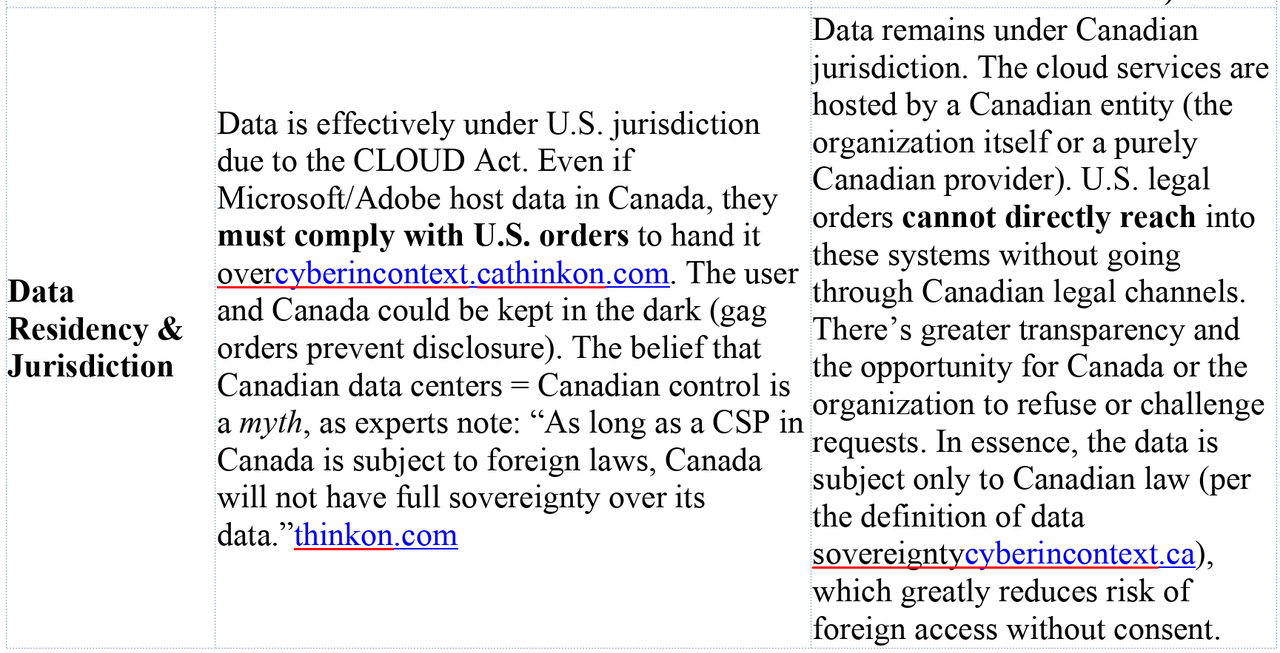

- Cloud File Services (OneDrive/SharePoint): In Scenario 1, most of the user’s files reside on OneDrive/SharePoint (which are part of Microsoft’s cloud) by design. For example, Windows 11 encourages storing Desktop/Documents in OneDrive. This means Microsoft already possesses copies of the user’s data on their servers, accessible to them with proper authorization. Similarly, the user’s emails in Exchange Online, calendar, contacts, Teams chats, and any content in the O365 ecosystem are on Microsoft’s infrastructure. The integration of the device with these cloud services creates a rich server-side target (discussed in the exfiltration section). Adobe content, if the user saves PDFs to Adobe’s cloud or uses Adobe Sign, is also stored on Adobe’s U.S.-based servers. Both Microsoft and Adobe, as U.S. companies, are subject to the CLOUD Act – under which they can be compelled to provide data in their possession to U.S. authorities, regardless of where that data is physically storedmicrosoft.comcyberincontext.ca. In essence, by using these services, the user’s data is readily accessible to the vendor (and thus to law enforcement with a warrant) without needing to touch the endpoint at all.

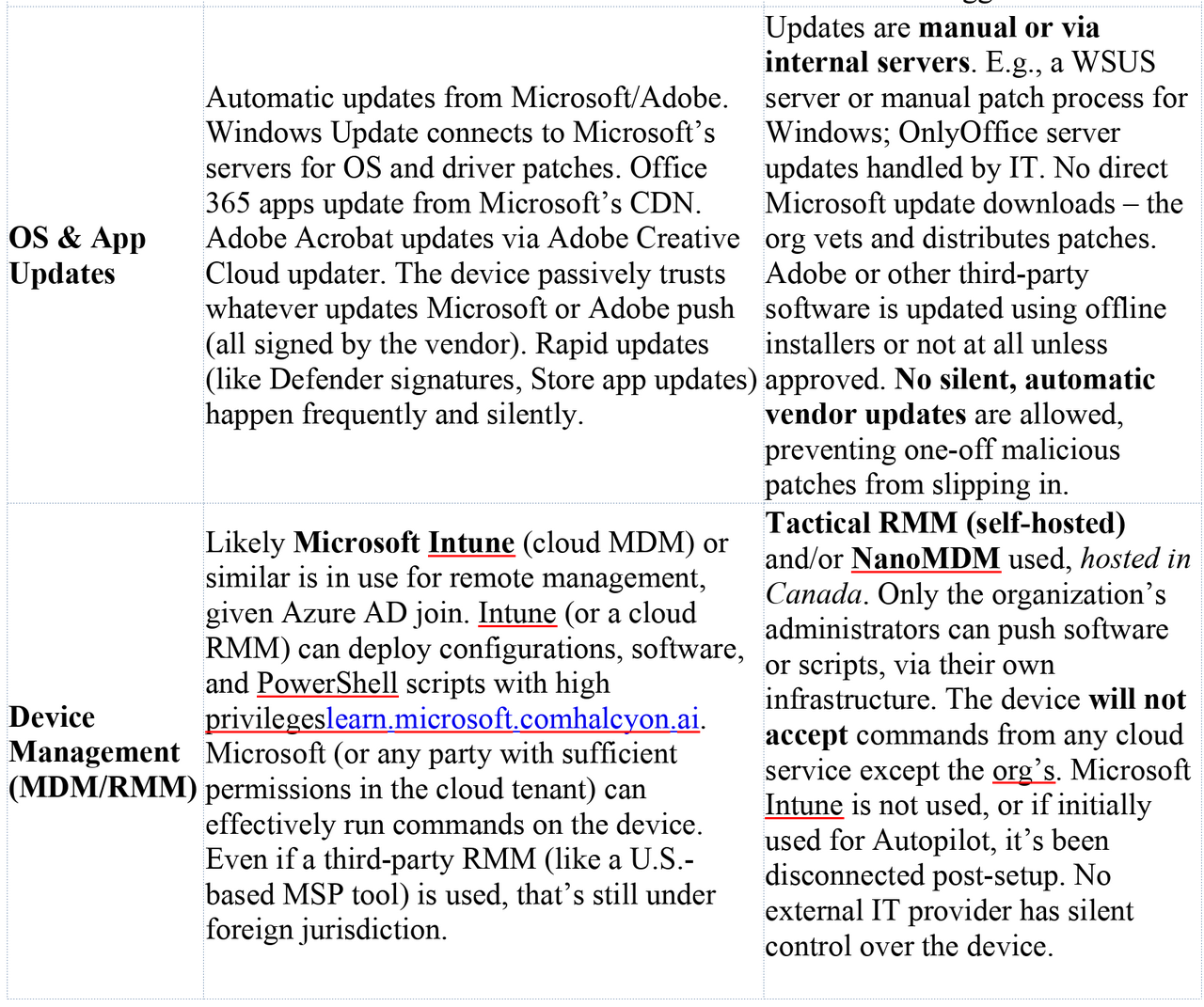

- Device Management & Trusted Execution: If the device is managed by Microsoft Intune (or a similar MDM), Microsoft or any party with control of the Intune tenant can remotely execute code or configuration on the endpoint. Intune allows admins to deploy PowerShell scripts and software packages to enrolled Windows devices silentlylearn.microsoft.comhalcyon.ai. These scripts can run as SYSTEM (with full privileges) if configured as such, and they do not require the user to be logged in or consentlearn.microsoft.com. In a normal enterprise, only authorized IT admins can create Intune deployments – but in a scenario of secret vendor cooperation, Microsoft itself (at the behest of a FISA order, for example) could potentially inject a script or policy into the Intune pipeline targeting this device. Because Intune is a cloud service, such an action might be done without the organization’s awareness (for instance, a malicious Intune policy could be created and later removed by someone with back-end access at Microsoft). The Intune management extension on the device would then execute the payload, which could harvest files, keystrokes, or other data. This would all appear as normal device management activity. In fact, attackers in the wild have used stolen admin credentials to push malware through Intune, masquerading as IT taskshalcyon.ai. Under state direction, the same could be done via Microsoft’s cooperation – the device trusts Intune and will run whatever it’s told, with the user none the wiser (no pop-up, nothing visible aside from maybe a transient process).

- Software Update / Supply Chain: Windows 11 trusts Microsoft-signed code updates implicitly. Microsoft could, under extreme circumstances, ship a targeted malicious update to this one device or a small set of devices. For example, a malicious Windows Defender signature update or a fake “security patch” could be crafted to include an implant. Normally, Windows Update deployments go to broad audiences, but Microsoft does have the ability to do device-specific targeting in certain cases (e.g., an Intune-managed device receiving a custom compliance policy, or hypothetically using the device’s unique ID in the update API). Even if true one-off targeting is difficult via Windows Update, Microsoft could exploit the Windows Defender cloud: as noted, by updating Defender’s cloud-delivered signatures, they might classify a particular internal tool or document as malware, which would cause Defender on the endpoint to quarantine or even upload it. There’s precedent for security tools being used this way – essentially turning the AV into an exfiltration agent by design (it’s supposed to send suspicious files to the cloud). Additionally, Microsoft Office and Edge browser periodically fetch updates from Microsoft’s CDN. A coerced update (e.g., a malicious Office add-in pushed via Office 365 central deployment) is conceivable, running with the user’s privileges when Office launches. Adobe similarly distributes updates for Acrobat/Creative Cloud apps. A state actor could pressure Adobe to issue a tampered update for Acrobat that only executes a payload for a specific user or org (perhaps triggered by an Adobe ID). Such a supply-chain attack is highly sophisticated and risky, and there’s no public evidence of Microsoft or Adobe ever doing one-off malicious updates. But from a purely technical standpoint, the channels exist and are trusted by the device – making them potential vectors if the vendor is forced to comply secretly. At the very least, Microsoft’s cloud control of the software environment (via updates, Store, and cloud configuration) means the attack surface is much broader compared to an isolated machine.

In summary, Scenario 1’s design means the vendor’s infrastructure has tentacles into the device for legitimate reasons (updates, sync, telemetry, management). Those same tentacles can be repurposed for covert access. The device frequently “calls home” to Microsoft and Adobe, providing an attacker with opportunities to piggyback on those connections or data stores.

Sovereign Controls (Scenario 2): In the sovereign configuration, the organization has deliberately shut off or internalized all those channels to block vendor access and eliminate quiet data leaks:

- No Cloud Data Storage: The user does not use OneDrive, SharePoint, Exchange Online, or Adobe Cloud. Therefore, there is no trove of files or emails sitting on Microsoft/Adobe servers to be subpoenaed. The data that would normally be in OneDrive is instead on Seafile servers physically in Canada. Emails are on a Canadian mail server. These servers are under the organization’s control, protected by Canadian law. Apple’s iCloud was a concern in the Mac scenario; here, Office 365 is the parallel – and it’s gone. Microsoft cannot hand over what it does not have. A U.S. agency cannot quietly fetch the user’s files from Microsoft’s cloud, because those files live only on the user’s PC and a Canadian server. (In the event they try legal means, they’d have to go through Canadian authorities and ultimately the org itself, which is not covert.) By removing U.S.-based cloud services, Scenario 2 closes the gaping vendor-mediated backdoor present in Scenario 1thinkon.comthinkon.com.

- Identity and Login: The machine is not Azure AD joined; it likely uses a local Active Directory or is standalone with a Keycloak-based login workflow. This means the device isn’t constantly checking in with Azure AD for token refresh or device compliance. Keycloak being on-premises ensures authentication (Kerberos/SAML/OIDC tickets, etc.) stay within the org. Microsoft’s identity control (so powerful in Scenario 1) is absent – no Azure AD Conditional Access, no Microsoft account tokens. Thus, there’s no avenue for Microsoft to, say, disable the account or alter conditional access policies to facilitate an attack. Moreover, BitLocker keys are only stored internally (like in AD or a secure vault). In Scenario 1, BitLocker recovery could be obtained from Azure AD by law enforcement (indeed, Windows 11 automatically uploads keys to Azure AD/Microsoft Account by defaultblog.elcomsoft.com). In Scenario 2, the keys are on Canadian infrastructure – a subpoena to Microsoft for them would turn up empty. Accessing them would require involving the organization or obtaining a Canadian warrant, again defeating covert action.

- Telemetry Disabled and Blocked: The organization in Scenario 2 uses both policy and technical controls to ensure Windows isn’t talking to Microsoft behind the scenes. Using Windows Enterprise features, admins set the diagnostic data level to “Security” (the minimal level, essentially off) and disable Windows Error Reporting, feedback hubs, etc. They deploy tools like O&O ShutUp10++ or scripted regedits to turn off even the consumer experience features that might leak data. Importantly, they likely implement network-level blocking for known telemetry endpoints (e.g. vortex.data.microsoft.com, settings-win.data.microsoft.com, and dozens of others). This is crucial because even with settings off, some background traffic can occur (license activation, time sync, etc.). The firewall might whitelist only a small set of necessary Microsoft endpoints (perhaps Windows Update if they don’t have WSUS, and even that might be routed through a caching server). In many lockdown guides, tools like Windows Defender’s cloud lookup, Bing search integration, and even the online certificate revocation checks can be proxied or blocked to avoid information leak. The result is that any unexpected communication to Microsoft’s servers would be anomalous. If, for instance, the workstation suddenly tried to contact an Azure AD or OneDrive endpoint, the local SOC would treat that as a red flag, since the device normally has no reason to do so. In effect, the background noise of vendor telemetry is dialed down to near-zero, so it’s hard for an attacker to hide in it – there is no benign “chatter” with Microsoft to blend withthinkon.comborncity.com. Microsoft loses visibility into the device’s state; Windows isn’t dutifully uploading crash dumps or usage data that could be mined. Adobe as well has no footprint – Acrobat isn’t logging into Adobe’s cloud, and any update checks are disabled (the org might update Acrobat manually or use an offline installer for Xodo/other PDF readers to avoid Adobe Updater service).

- Internal Update and Patching: Rather than letting each PC independently pull updates from Microsoft, Scenario 2 uses a controlled update process. This could be an on-premises WSUS (Windows Server Update Services) or a script-driven manual update where IT downloads patches, tests them, and then deploys to endpoints (possibly via Tactical RMM or Group Policy). By doing this, the org ensures that no unvetted code runs on the workstation. Microsoft cannot silently push a patch to this machine without the IT team noticing, because the machine isn’t automatically asking Microsoft for updates – it’s asking the internal server, or nothing at all until an admin intervenes. The same goes for application software: instead of Microsoft Office 365 (with its monthly cloud-driven updates), they likely use OnlyOffice which the org updates on their own schedule. Any software that does auto-update (maybe a browser) would be configured to use an internal update repository or simply be managed by IT. This air-gap of the update supply chain means even if Microsoft created a special update, the machine wouldn’t receive it unless the org’s IT approves. Compare this to Scenario 1, where something like a Windows Defender signature update arrives quietly every few hours from Microsoft – in Scenario 2, even Defender’s cloud features might be turned off or constrained to offline mode. Overall, the software trust boundary is kept local: the workstation isn’t blindly trusting the Microsoft cloud to tell it what to install.

- Self-Hosted Device Management (MDM/RMM): Rather than Intune (cloud MDM) or other third-party SaaS management, Scenario 2 employs Tactical RMM and potentially NanoMDM (if they needed an MDM protocol for certain Apple-like enrollment, though for Windows, likely traditional AD + RMM suffices). These tools are hosted on servers in Canada, under the org’s direct control. No outside entity can initiate a management action on the device because the management servers aren’t accessible to Microsoft or any third party. Intune uses Microsoft’s push notification service and lives in Azure – not the case here. Tactical RMM agent communicates only with the org’s server, over secure channels. While it’s true that Microsoft’s push notification (WNS) is used by some apps, Tactical RMM likely uses its own agent-check in mechanism (or could use SignalR/websockets, etc., pointed to the self-hosted server). There is also no “vendor backdoor” account; whereas Jamf or Intune are operated by companies that could be served legal orders, Tactical RMM is operated by the organization itself. For an outside agency to leverage it, they would need to either compromise the RMM server (a direct hack, not just legal compulsion) or go through legal Canadian channels to ask the org to use it – which of course ruins the secrecy. Furthermore, because the device is still Windows, one might consider Microsoft’s own services like the Windows Push Notification Services (WNS) or Autopilot. However, if this device was initially provisioned via Windows Autopilot, it would have been registered in Azure AD – Scenario 2 likely avoids Autopilot altogether or used it only in a minimal capacity then severed the link. Thereafter, no persistent Azure AD/Autopilot ties remain. And while Windows does have WNS for notifications, unless a Microsoft Store app is listening (which in this setup, probably not much is – no Teams, no Outlook in this scenario), there’s little WNS traffic. Crucially, WNS by itself cannot force the device to execute code; it delivers notifications for apps, which are user-facing. So unlike Apple’s APNs+MDM combo, Windows has nothing similar that Microsoft can silently exploit when the device isn’t enrolled in their cloud.

Putting it together, Scenario 2’s philosophy is “disable, replace, or closely monitor” any mechanism where the OS or apps would communicate with or receive code from an external vendor. The attack surface for vendor-assisted intrusion is dramatically reduced. Microsoft’s role is now mostly limited to being the OS provider – and Windows, while still ultimately Microsoft’s product, is being treated here as if it were an offline piece of software. The organization is asserting control over how that software behaves in the field, rather than deferring to cloud-based automation from Microsoft.

Summary of Vendor-Controlled Surfaces: The table below highlights key differences in control and telemetry between the Microsoft-integrated Scenario 1 and the sovereign Scenario 2:

Feasible Exfiltration Strategies Under Lawful Vendor Cooperation

Given the above surfaces, a red team (or state actor with legal authority) aiming to covertly extract sensitive data would have very different options in Scenario 1 vs Scenario 2. The goal of such an actor is to obtain specific files, communications, or intelligence from the target workstation without the user or organization detecting the breach, and ideally without deploying obvious “malware” that could be forensically found later. We examine potential strategies in each scenario:

Scenario 1 (Microsoft/Adobe-Integrated) – Potential Exfiltration Paths:

- Server-Side Cloud Data Dump (No Endpoint Touch): The path of least resistance is to go after the data sitting in Microsoft’s and Adobe’s clouds, entirely outside the endpoint. Microsoft can be compelled under a sealed warrant or FISA order to provide all data associated with the user’s Office 365 account – and do so quietlymicrosoft.comcyberincontext.ca. This would include the user’s entire Exchange Online mailbox (emails, attachments), their OneDrive files, any SharePoint/Teams files or chat history, and detailed account metadata. For example, if the user’s Documents folder is in OneDrive (common in enterprise setups), every file in “Documents” is already on Microsoft’s servers. Microsoft’s compliance and eDiscovery tools make it trivial to collect a user’s cloud data (administrators do this for legal holds regularly – here we assume Microsoft acts as the admin under court order). The key point: this method requires no action on the endpoint itself. It’s entirely a cloud-to-cloud transfer between Microsoft and the requesting agency. It would be invisible to the user and to the organization’s IT monitoring. Microsoft’s policy is to notify enterprise customers of legal demands only if legally allowed and to redirect requests to the customer where possiblemicrosoft.com. But in national security cases with gag orders, they are prohibited from notifying. Historically, cloud providers have handed over data without users knowing when ordered by FISA courts or via National Security Letters. As one Canadian sovereignty expert summarized, if data is in U.S. providers’ hands, it can be given to U.S. authorities “without the explicit authorization” or even knowledge of the foreign governmentcyberincontext.cacyberincontext.ca. Apple’s scenario had iCloud; here, Office 365 is no different. Microsoft’s own transparency report confirms they do turn over enterprise customer content in a (small) percentage of casesmicrosoft.com. Adobe, likewise, can be served a legal demand for any documents or data the user stored in Adobe’s cloud (for instance, PDF files synced via Acrobat’s cloud or any records in Adobe Sign or Creative Cloud storage). In short, for a large portion of the user’s digital footprint, the fastest way to get it is straight from the source – the cloud backend – with zero traces on the endpoint.

- Intune or Cloud RMM-Orchestrated Endpoint Exfiltration: For any data that isn’t in the cloud (say, files the user intentionally kept only on the local machine or on a network drive not covered above), the adversary can use the device management channel to pull it. If the workstation is Intune-managed, a covert operator with influence over Microsoft could push a malicious script or payload via Intune. Microsoft Intune allows delivery of PowerShell scripts that run with admin privileges and no user interactionlearn.microsoft.com. A script could be crafted to, for example, compress targeted directories (like C:\Users\\Documents\ or perhaps the entire user profile) and then exfiltrate them. Exfiltration could be done by uploading to an external server over HTTPS, or even by reusing a trusted channel – e.g., the script might quietly drop the archive into the user’s OneDrive folder (which would sync it to cloud storage that Microsoft can then directly grab, blending with normal OneDrive traffic). Alternatively, Intune could deploy a small agent (packaged as a Win32 app deployment) that opens a secure connection out to a collection server and streams data. Because Intune actions are fully trusted by the device (they’re signed by Microsoft and executed by the Intune Management Extension which runs as SYSTEM), traditional security software would likely not flag this as malware. It appears as “IT administration.” From a detection standpoint, such an exfiltration might leave some logs on the device (script execution events, etc.), but these could be hard to catch in real time. Many organizations do not closely monitor every Intune action, since Intune is expected to be doing things. A sophisticated attacker could even time the data collection during off-hours and possibly remove or hide any local logs (Intune itself doesn’t log script contents to a readily visible location – results are reported to the Intune cloud, which the attacker could scrub). If the organization instead uses a third-party cloud RMM (e.g., an American MSP platform) to manage PCs, a similar tactic applies: the provider could silently deploy a tool or run a remote session to grab files, all under the guise of routine remote management. It’s worth noting that criminal attackers have exploited exactly this vector by compromising MSPs – using management tools to deploy ransomware or steal data from client machines. In our lawful scenario, it’s the vendor doing it to their client. The risk of detection here is moderate: If the organization has endpoint detection (EDR) with heuristics, it might notice an unusual PowerShell process or an archive utility running in an uncommon context. Network monitoring might catch a large upload. But an intelligent exfiltration could throttle and mimic normal traffic (e.g., use OneDrive sync or an HTTPS POST to a domain that looks benign). Because the device is expected to communicate with Microsoft, and the script can leverage that (OneDrive or Azure blob storage as a drop point), the SOC might not see anything alarming. And crucially, the organization’s administrators would likely have no idea that Intune was weaponized against them; they would assume all Intune actions are their own. Microsoft, as the Intune service provider, holds the keys in this scenario.

- OS/Software Update or Defender Exploit: Another covert option is for Microsoft to use the software update mechanisms to deliver a one-time payload. For example, Microsoft could push a targeted Windows Defender AV signature update that flags a specific sensitive document or database on the system as malware, causing Defender to automatically upload it to the Microsoft cloud for “analysis.” This is a clever indirect exfiltration – the document ends up in Microsoft’s hands disguised as a malware sample. By policy, Defender is not supposed to upload files likely to contain personal data without user confirmationsecurity.stackexchange.com, but Microsoft has latitude in what the engine considers “suspicious.” A tailor-made signature could trigger on content that only the target has (like a classified report), and mark it in a way that bypasses the prompt (for executables, Defender doesn’t prompt – it just uploads). The user might at most see a brief notification that “malware was detected and removed” – possibly something they’d ignore or that an attacker could suppress via registry settings. Beyond AV, Microsoft could issue a special Windows Update (e.g., a cumulative update or a driver update) with a hidden payload. Since updates are signed by Microsoft, the device will install them trusting they’re legitimate. A targeted update could, for instance, activate the laptop’s camera/microphone briefly or create a hidden user account for later remote access. The challenge with Windows Update is delivering it only to the target device: Microsoft would have to either craft a unique hardware ID match (if the device has a unique driver or firmware that no one else has) or use Intune’s device targeting (blurring lines with the previous method). However, consider Microsoft Office macro or add-in updates: If the user runs Office, an update to Office could include a macro or plugin that runs once to collect data then self-delete. Microsoft could also abuse the Office 365 cloud management – Office has a feature where admins can auto-install an Add-in for users (for example, a compliance plugin). A rogue Add-in (signed by Microsoft or a Microsoft partner) could run whenever the user opens Word/Excel, and quietly copy contents to the cloud. Since it originates from Office 365’s trusted app distribution, the system and user again trust it. Adobe could do something analogous if the user frequently opens Acrobat: push an update that, say, logs all PDF text opened and sends to Adobe analytics. These supply-chain style attacks are complex and risk collateral impact if not extremely narrowly scoped. But under a lawful secret order, the vendor might deploy it only to the specific user’s device or account. Importantly, all such approaches leverage the fact that Microsoft or Adobe code executing on the machine is trusted and likely unmonitored. An implant hidden in a genuine update is far less likely to be caught by antivirus (it is the antivirus, in the Defender case, or it’s a signed vendor binary).

- Leveraging Cloud Credentials & Sessions: In addition to direct data grabbing, an actor could exploit the integration of devices with cloud identity. For instance, with cooperation from Microsoft, they might obtain a token or cookie for the user’s account (or use a backdoor into the cloud service) to access data as if they were the user. This isn’t exactly “exfiltration” because it’s more about impersonating the user in the cloud (which overlaps with server-side data access already discussed). Another angle: using Microsoft Graph API or eDiscovery via the organization’s tenant. If law enforcement can compel Microsoft, they might prefer not to break into the device at all but rather use Microsoft’s access to the Office 365 tenant data. However, Microsoft’s policy for enterprise is usually to refer such requests to the enterprise IT (they said they try to redirect law enforcement to the customer for enterprise data)microsoft.com. Under FISA, they might not have that luxury and might be forced to pull data themselves.

- Adobe-Specific Vectors: If the user’s workflow involves Adobe cloud (e.g., scanning documents to Adobe Scan, saving PDFs in Acrobat Reader’s cloud, or using Adobe Creative Cloud libraries), Adobe can be asked to hand over that content. Adobe’s Law Enforcement guidelines (not provided here, but in principle) would allow disclosure of user files stored on their servers with a warrant. Adobe doesn’t have the same device management reach as Microsoft, but consider that many PDF readers (including Adobe’s) have had web connectivity – for license checks, updates, or even analytics. A cooperation could involve Adobe turning a benign process (like the Acrobat update service) into an information collector just for this user. This is more speculative, but worth noting that any software that auto-updates from a vendor is a potential carrier.

In practice, a real-world adversary operating under U.S. legal authority would likely choose the least noisy path: first grab everything from the cloud, since that’s easiest and stealthiest (the user’s OneDrive/Email likely contain the bulk of interesting data). If additional info on the endpoint is needed (say there are files the user never synced or an application database on the PC), the next step would be to use Intune or Defender to snatch those with minimal footprint. Direct exploitation (hacking the machine with malware) might be a last resort because it’s riskier to get caught and not necessary given the “insider” access the vendors provide. As noted by observers of the CLOUD Act, “Microsoft will listen to the U.S. government regardless of … other country’s laws”, and they can do so without the customer ever knowingcyberincontext.cacyberincontext.ca. Scenario 1 basically hands the keys to the kingdom to the cloud providers – and by extension to any government that can legally compel those providers.

Scenario 2 (Sovereign Setup) – Potential Exfiltration Paths:

In Scenario 2, the easy buttons are gone. There is no large cache of target data sitting in a U.S. company’s cloud, and no remote management portal accessible by a third-party where code can be pushed. A red team or state actor facing this setup has far fewer covert options:

- Server-Side Request to Sovereign Systems: The direct approach would be to serve a legal demand to the organization or its Canadian hosting providers for the data (through Canadian authorities). But this is no longer covert – it would alert the organization that their data is wanted, defeating the stealth objective. The question we’re asking is about silent exfiltration under U.S. legal process, so this straightforward method (MLAT – Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty – or CLOUD Act agreements via Canada) is outside scope because it’s not a red-team stealth action, it’s an official process that the org would see. The whole point of the sovereign model is to require overt legal process, thereby preventing secret data access. So assuming the adversary wants to avoid tipping off the Canadians, they need to find a way in without help from the target or Canadian courts.

- OS Vendor (Microsoft) Exploitation Attempts: Even though the device isn’t chatting with Microsoft, it does run Windows, which ultimately trusts certain Microsoft-signed code. A very determined attacker could try to use Microsoft’s influence at the OS level. One theoretical vector is Windows Update. If the org isn’t completely air-gapped, at some point they will apply Windows patches (maybe via an internal WSUS that itself syncs from Microsoft, or by downloading updates). Microsoft could create a poisoned update that only triggers malicious behavior on this specific machine or in this specific environment. This is extremely difficult to do without affecting others, but not impossible. For instance, the malicious payload could check for a particular computer name, domain, or even a particular hardware ID. Only if those match (i.e., it knows the target’s unique identifiers) does it execute the payload; otherwise it stays dormant to avoid detection elsewhere. Microsoft could slip this into a cumulative update or a driver update. However, because in Scenario 2 updates are manually vetted, the IT team might detect anomalous changes (they could compare the update files’ hashes with known-good or with another source). The risk of discovery is high – any administrator doing due diligence would find that the hash of the update or the behavior of the system after the update is not normal. Also, Windows updates are heavily signed and monitored; even Microsoft would fear doing this as it could be noticed by insiders or by regression testing (unless it’s truly a one-off patch outside the normal channels).

- Another attempt: targeted exploitation via remaining Microsoft connections. Perhaps the machine occasionally connects to Microsoft for license activation or time synchronization. Maybe the Windows time service or license service could be subverted to deliver an exploit payload (for instance, a man-in-the-middle if they know the machine will contact a Microsoft server – but if DNS is locked down, this is unlikely). If Windows Defender cloud features were on (they likely aren’t), Microsoft could try to mark a needed system file as malware to trick the system into deleting it (sabotage rather than exfiltration). But here we need exfiltration: One cunning idea would be if the device uses any cloud-based filtering (like SmartScreen for downloads or certificate revocation checks), an attacker could host a piece of bait data in a place that causes the workstation to reach out. Honestly, in this scenario, the organization has probably disabled or internalized even those (e.g., using an offline certificate revocation list and not relying on Microsoft’s online checks).

- Microsoft could also abuse the Windows hardware root of trust – for example, pushing a malicious firmware via Windows Update if the machine is a Surface managed by Microsoft. In 2025, some PC firmware updates come through Windows Update. A malicious firmware could implant a backdoor that collects data and transmits it later when network is available. But again, in Scenario 2 the machine isn’t supposed to automatically take those updates, and a custom firmware with backdoor is likely to get noticed eventually.

- All these OS-level attacks are highly speculative and risky. They border on active cyberwarfare by Microsoft against a customer, which is not something they’d do lightly even under legal orders (and they might legally challenge an order to do so as beyond the pale). The difference from Scenario 1 is that here covert access would require a compromise of security safeguards, not just leveraging normal features.

- Compromise of Self-Hosted Infrastructure (Supply Chain Attack): With no voluntary backdoor, an adversary might attempt to create one by compromising the very tools that make the system sovereign. For instance, Tactical RMM or Seafile or Keycloak could have vulnerabilities. A state actor could try to exploit those to gain entrance. If, say, the Tactical RMM server is Internet-facing (for remote access by admins), an undisclosed vulnerability or an admin credential leak could let the attacker in. Once inside the RMM, they could use it exactly as the org’s IT would – deploy a script or new agent to the workstation to collect data. Similarly, if Seafile or the mail server has an admin interface exposed, an attacker might exfiltrate data directly from those servers (bypassing the endpoint entirely). However, these approaches are no longer vendor cooperation via legal means; they are hacking. The U.S. government could hack a Canadian server (NSA style) but that moves out of the realm of legal compulsion into the realm of clandestine operation. It also carries political risk if discovered. From a red-team perspective, one might simulate an insider threat or malware that compromises the internal servers – but again, that likely wouldn’t be considered a “legal process” vector. Another supply chain angle: if the organization updates Tactical RMM or other software from the internet, an adversary could attempt to Trojanize an update for those tools (e.g., compromise the GitHub release of Tactical RMM to insert a backdoor which then the org unwittingly installs). This actually has historical precedent (attackers have compromised open-source project repositories to deliver malware). If the U.S. had an avenue to do that quietly, they might attempt it. But targeting a specific org via a public open-source project is iffy – it could affect others and get noticed.

- Physical Access & Key Escrow: A traditional law-enforcement approach to an encrypted device is to obtain the encryption key via the vendor. In Scenario 1, that was viable (BitLocker key from Azure AD). In Scenario 2, it’s not – the key isn’t with Microsoft. If U.S. agents somehow got physical possession of the laptop (say at a border or during travel), they couldn’t decrypt it unless the org provided the key. So physically seizing the device doesn’t grant access to data (the data is safe unless they can force the user or org to give up keys, which again would be overt). So they are compelled to remote tactics.

- Insider or Side-Channel Tricks: Outside the technology, the adversary might resort to good old human or side-channel methods. For instance, could they persuade an insider in the Canadian org to secretly use the RMM to extract data? That’s a human breach, not really vendor cooperation. Or might they attempt to capture data in transit at network chokepoints? In Scenario 2, most data is flowing within encrypted channels in Canada. Unless some of that traffic crosses U.S. infrastructure (which careful design would avoid), there’s little opportunity. One could imagine if the user emailed someone on Gmail from their sovereign system – that email lands on Google, a U.S. provider, where it could be collected. But that’s straying from targeting the workstation itself. It just highlights that even a sovereign setup can lose data if users interact with foreign services, but our assumption is the workflow keeps data within controlled bounds.

In essence, Scenario 2 forces an attacker into the realm of active compromise with a high risk of detection. There’s no silent “API” to request data; no friendly cloud admin to insert code for you. The attacker would have to either break in or trick someone, both of which typically leave more traces. Microsoft’s influence is reduced to the operating system updates, and if those are controlled, Microsoft cannot easily introduce malware without it being caught. This is why from a sovereignty perspective, experts say the only way to truly avoid CLOUD Act exposure is to not use U.S.-based products or keep them completely offlinecyberincontext.cacyberincontext.ca. Here we still use Windows (a U.S. product), but with heavy restrictions; one could go even further and use a non-U.S. OS (Linux) to remove Microsoft entirely from the equation, but that’s beyond our two scenarios.

To summarize scenario 2’s situation: a “red team” with legal powers finds no convenient backdoor. They might consider a very targeted hacking operation (maybe using a Windows 0-day exploit delivered via a phishing email or USB drop). But that moves firmly into illegal hack territory rather than something enabled by legal compulsion, and it risks alerting the victim if anything goes wrong. It’s a last resort. The stark difference with scenario 1 is that here the adversary cannot achieve their objective simply by serving secret court orders to service providers – those providers either don’t have the data or don’t have the access.

Detection Vectors and SOC Visibility

From the perspective of the organization’s Security Operations Center (SOC) or IT security team, the two scenarios also offer very different chances to catch a breach in progress or to forensically find evidence after the fact. A key advantage of the sovereign approach is not just reducing attack surface, but also increasing the visibility of anything abnormal, whereas the integrated approach can allow a lot of activity to hide in plain sight.

In Scenario 1, many of the potential exfiltration actions would appear as normal or benign on the surface. If Microsoft pulls data from OneDrive or email, that happens entirely in the cloud – the endpoint sees nothing. The user’s PC isn’t doing anything differently, and the organization’s network monitoring will not catch an external party retrieving data from Microsoft’s datacenters. The SOC is blind to that; they would have to rely on Microsoft’s transparency reports or an unlikely heads-up, which typically come long after the fact if at all (and gag orders often prevent any notificationmicrosoft.commicrosoft.com). If Intune is used to run a script on the endpoint, from the device’s viewpoint it’s just the Intune Management Extension (which is a legitimate, constantly-running service) doing its job. Many SOC tools will whitelist Intune agents because they are known good. Unless the defenders have set up specific alerts like “alert if Intune runs a PowerShell containing certain keywords or if large network transfers occur from Intune processes,” they might not notice. The same goes for using Defender or updates: if Defender suddenly declares a file malicious, the SOC might even think “good, it caught something” rather than suspecting it was a trigger to steal that file. Network-wise, Scenario 1’s workstation has frequent connections to Microsoft cloud endpoints (OneDrive sync traffic, Outlook syncing email, Teams, etc.). This means even a somewhat larger data transfer to Microsoft could blend in. For example, OneDrive might already be uploading large files; an attacker adding one more file to upload wouldn’t be obvious. If an exfiltration script sends data to https://login.microsoftonline.com or some Azure Blob storage, many network monitoring systems would view that as normal Microsoft traffic (since blocking Microsoft domains is not feasible in this environment). Additionally, because IT management is outsourced in part to Microsoft’s cloud, the org’s administrators might not have logs of every action. Intune activities are logged in the Intune admin portal, but those logs could potentially be accessed or altered by Microsoft if they were carrying out a secret operation (at least, Microsoft as the service provider has the technical ability to manipulate back-end data). Moreover, the organization might not even be logging Intune actions to their SIEM, so a one-time script push might go unnoticed in their own audit trail.

It’s also worth considering that in Scenario 1, much of the security stack might itself be cloud-based and under vendor control. For example, if the organization uses Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (the cloud-managed EDR) instead of Wazuh, then Microsoft actually has direct insight into the endpoint security events and can even run remote response actions. (They said default Defender AV in this case, but many enterprises would have Defender for Endpoint, which allows remote shell access to PCs for incident response. A malicious insider at Microsoft with the right access could initiate a live response session to dump files or run commands, all under the guise of “security investigation.”) Even without that, default Defender AV communicates with Microsoft cloud for threat intelligence – something a sophisticated attacker could potentially leverage or at least use to their advantage to mask communications.

Overall, detection in Scenario 1 requires a very vigilant and somewhat paranoid SOC – one that assumes the trusted channels could betray them. Most organizations do not assume Intune or O365 will be turned against them by the service provider. Insider threat from the vendor is not typically modeled. Therefore, they may not be watching those channels closely. As a result, an exfiltration could succeed with low risk of immediate detection. Forensic detection after the fact is also hard – how do you distinguish a malicious Intune script from a legitimate one in logs, especially if it’s been removed? The endpoint might show evidence of file archives or PowerShell execution, which a skilled investigator could find if they suspect something. But if they have no reason to suspect, they might never look. And if Microsoft provided data directly from cloud, there’d be nothing on the endpoint to find at all.

In Scenario 2, the situation is reversed. The workstation is normally quiet on external networks; thus, any unusual outgoing connection or process is much more conspicuous. The SOC likely has extensive logging on the endpoint via Wazuh (which can collect Windows Event Logs, Sysmon data, etc.) and on network egress points. Since the design assumption is “we don’t trust external infrastructure,” the defenders are more likely to flag any contact with an external server that isn’t explicitly known. For instance, if somehow an update or process tried to reach out to a Microsoft cloud URL outside the scheduled update window, an alert might fire (either host-based or network-based). The absence of constant O365 traffic means the baseline is easier to define. They might even have host-based firewalls (like Windows Firewall with white-list rules or a third-party firewall agent) that outright block unexpected connections and log them.

If an attacker tried an Intune-like approach by compromising Tactical RMM, the defenders might notice strange behavior on the RMM server or an unplanned script in the RMM logs. Given the sensitivity, it’s likely the org closely monitors administrative actions on their servers. And any outsider trying to use those tools would have to get past authentication – not trivial if properly secured. Even a supply chain backdoor, if triggered, could be caught by behavior – e.g., if an OnlyOffice process suddenly tries to open a network connection to an uncommon host, the SOC might detect that via egress filtering.

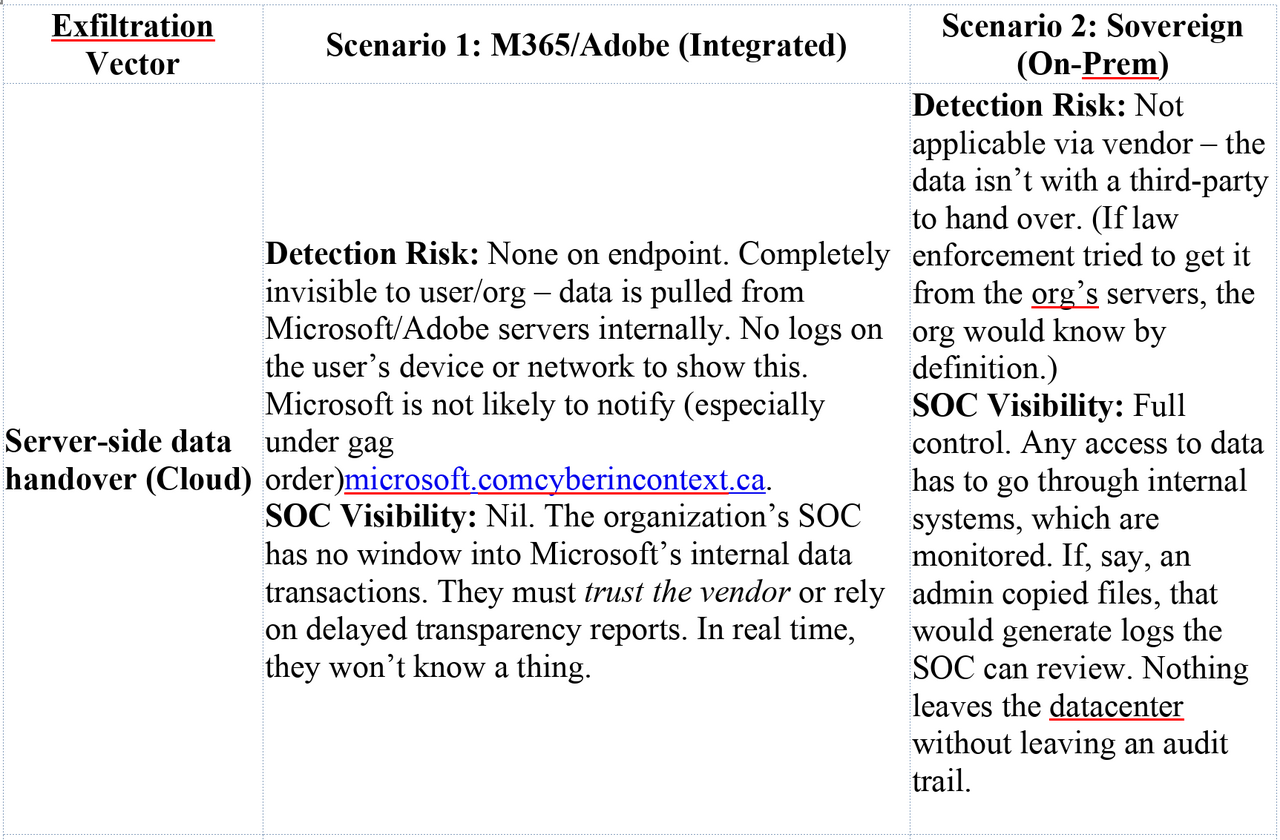

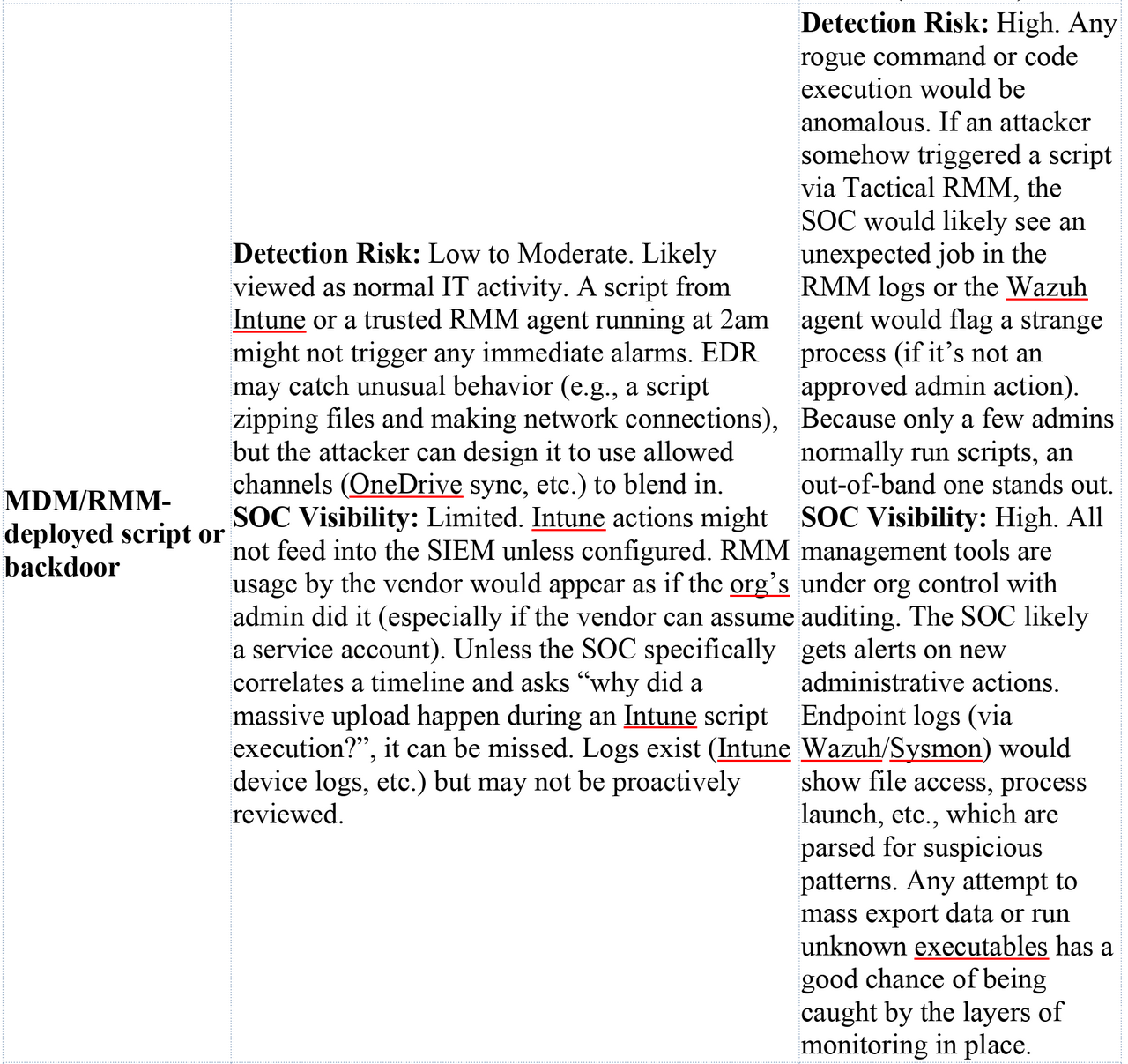

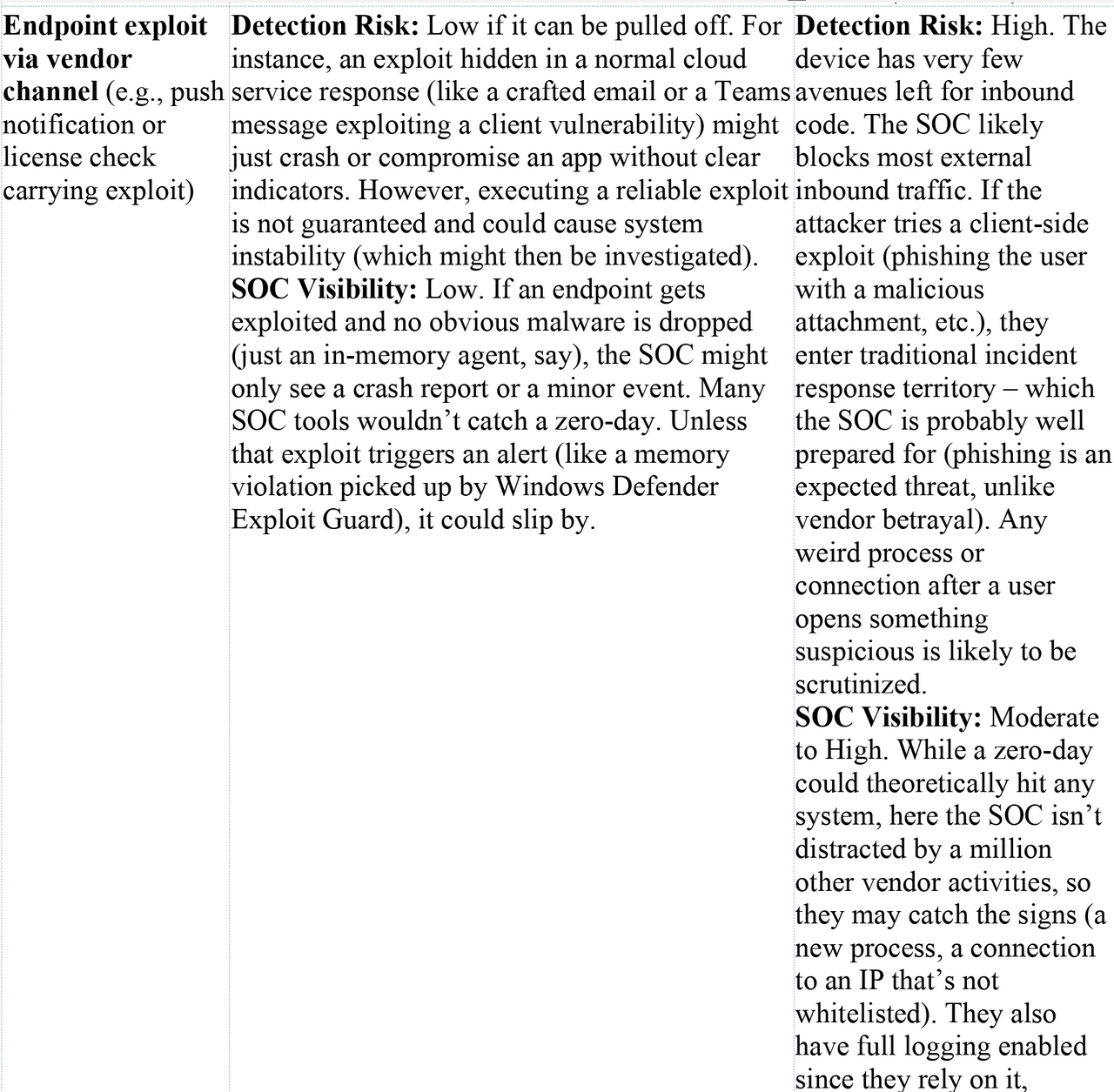

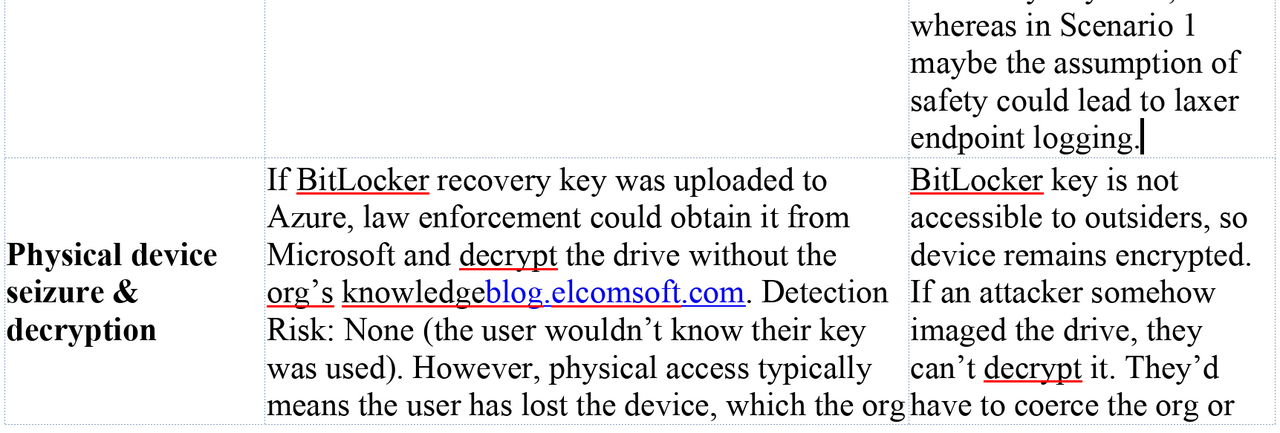

Table: Detection and Visibility Comparison (illustrating how different exfil vectors might or might not be detected in each scenario):

To boil it down: Scenario 1 provides plentiful cover and plausible deniability for an attack, while Scenario 2 forces the attack into the light or into more aggressive tactics that are easier to catch. In Scenario 1, the SOC might not even have the tools to detect a malicious vendor action, because those actions exploit the very trust and access that the org granted. As one analogy, Scenario 1 is like having a security guard (Microsoft) who has a master key to your building – if that guard is coerced or turns, they can enter and leave without breaking any windows, and your alarms (which trust the guard) won’t sound. Scenario 2 is like having no master key held by outsiders – any entry has to break a lock or window, which is obviously more likely to set off alarms or be noticed.

Risks, Limitations, and Sovereignty Impacts

The two scenarios illustrate a classic trade-off between convenience and control (or sovereignty). Scenario 1, the Microsoft 365 route, offers seamless integration, high productivity, and less IT overhead – but at the cost of autonomy and potential security exposure. Scenario 2 sacrifices some of that convenience for the sake of data sovereignty, at the cost of more complexity and responsibility on the organization’s side. Let’s unpack the broader implications:

Scenario 1 (Integrated with U.S. Cloud Services): Here, the organization enjoys state-of-the-art cloud tools and probably lower IT burden (since Microsoft handles identity management infrastructure, update delivery, server maintenance for Exchange/SharePoint, etc.). Users likely have a smooth experience with their files and emails syncing across devices, rich collaboration features, and so on. However, the sovereignty risk is significant. As Microsoft’s own representative admitted in 2025, if the U.S. government comes knocking for data – even data stored in a foreign jurisdiction – Microsoft will hand it over, “regardless of [Canadian] or other country’s domestic laws.”cyberincontext.cacyberincontext.ca Data residency in Canada does not equal protection, because U.S. law (CLOUD Act) compels U.S. companies to complythinkon.com. This directly undermines the concept of “Canada’s right to control access to its digital information subject only to Canadian laws”cyberincontext.ca. In Scenario 1, Canadian law is effectively sidestepped; the control is ceded to U.S. law once data is in Microsoft’s cloud. For a public sector or sensitive organization, this means potentially breaching legal requirements (many Canadian government departments have policies against certain data leaving Canada – yet using O365 could violate the spirit of that if not the letter, due to Cloud Act). The national security implication is that foreign agencies might get intelligence on Canadian operations without Canadian oversight. The scenario text mentioned that even Department of National Defence (DND/CAF) uses “Defence 365” – a special Microsoft 365 instance – and that in theory none of that is immune to U.S. subpoenascyberincontext.ca. This is a glaring issue: it means a foreign power could access a nation’s defense data covertly. As a result, experts and officials have been raising alarms. For example, Canada’s own Treasury Board Secretariat acknowledged that using foreign-run clouds means “Canada cannot ensure full sovereignty over its data.”thinkon.com And commentators have said this “undermines our national security and exposes us to foreign interference”, calling for sovereign cloud solutionsthinkon.comthinkon.com. In everyday terms, Scenario 1 is high-risk if one’s threat model includes insider threat at the vendor or foreign government orders. From a red-team perspective, Scenario 1 is like an open barn door: multiple avenues exist to exfiltrate data with minimal chance of getting caught. The defending org in Scenario 1 might also have a false sense of security – because everything is “managed” by reputable companies, they might invest less in their own monitoring (assuming Microsoft will take care of security). That complacency can lead to blind spots, as we described in detection. Finally, there’s also a vendor lock-in and reliability concern: reliance on Microsoft/Adobe means if those services go down or if the relationship sours (imagine political sanctions or trade disputes), the organization could be cut off. The ThinkOn blog cited a warning that the U.S. could even direct cloud providers to cut off Canadian clients in extreme scenariosthinkon.com. That’s an extreme case, but not impossible if geopolitics worsened. Essentially, Scenario 1 trades some sovereignty for convenience, and that comes with latent risks that may not manifest until a crisis – at which point it’s too late to easily disentangle.

Scenario 2 (Fully Sovereign in Canada): This setup is aligned with the idea of a “Canadian Sovereign Cloud and Workplace”. The clear benefit is that it dramatically reduces the risk of unauthorized foreign access. If the U.S. wants data from this organization, it cannot get it behind the scenes; it would have to go through diplomatic/legal channels, which involve Canadian authorities. The organization would likely be aware and involved, allowing them to protect their interests (perhaps contesting the request or ensuring it’s scoped properly). This upholds the principle of data sovereignty – Canadian data subject to Canadian law first and foremost. Security-wise, Scenario 2 minimizes the attack surface from the supply-chain/insider perspective. There’s no easy vendor backdoor, so attacks have to be more direct, which are easier to guard against. The organization has complete control over patching, configurations, and data location, enabling them to apply very strict security policies (like network segmentation, custom hardening) without worrying about disrupting cloud connectivity. For example, they can disable all sorts of OS features that phone home, making the system cleaner and less porous. Visibility and auditability are superior: all logs (from OS, apps, servers) are owned by the org, which can feed them into Wazuh SIEM and analyze for anomalies. There’s no “shadow IT” in the form of unknown cloud processes. In terms of compliance, this scenario likely meets Canadian data residency requirements for even the highest protected levels (since data never leaves Canadian-controlled facilities).

However, Scenario 2 has trade-offs and limitations. Firstly, the organization needs the IT expertise and resources to run these services reliably and securely. Microsoft 365’s appeal is that Microsoft handles uptime, scaling, and security of the cloud services. In Scenario 2, if the Seafile server crashes or the mail server is slow, it’s the organization’s problem to fix. They need robust backups, disaster recovery plans, and possibly redundant infrastructure to match the reliability of Office 365. This can be costly. Secondly, security of the sovereign stack itself must be top-notch. Running your own mail server, file cloud, etc., introduces the possibility of misconfigurations or vulnerabilities that attackers (including foreign ones) can target. For example, if the admin forgets to patch the mail server, an external hacker might break in – a risk that would have been shouldered by Microsoft in the cloud model. That said, one might argue that at least if a breach happens, the org finds out (they see it directly, rather than a cloud breach that might be hidden). Another challenge is feature parity and user experience. Users might find OnlyOffice or Thunderbird not as slick or familiar as the latest Office 365 apps. Collaboration might be less efficient (though OnlyOffice and Seafile do allow web-based co-editing, it might not be as smooth as SharePoint/OneDrive with Office Online). Integration between services might require more effort (Keycloak can unify login, but not all apps might be as seamlessly connected as the Microsoft ecosystem). Training and change management are needed to ensure users adopt the new tools properly and don’t try to circumvent them (like using personal Dropbox or something, which would undermine the whole setup). Therefore, strong policies and user education are needed to truly reap the sovereignty benefits.

From a red team perspective focusing on lawful U.S. access, Scenario 2 is almost a dead-end – which is exactly the point. It “frustrates attempts at undetected exfiltration,” as we saw. This aligns with the stance of Canadian cyber officials who push for reducing reliance on foreign tech: “the only likely way to avoid the risk of U.S. legal requests superseding [our] law is not to use the products of U.S.-based organizations”cyberincontext.ca. Our sovereign scenario still uses Windows, which is U.S.-made, but it guts its cloud connectivity. Some might push even further (Linux OS, Canadian hardware if possible) for extreme cases, but even just isolating a mainstream OS is a huge improvement. The cost of silent compromise becomes much higher – likely high enough to deter all but the most resourceful adversaries, and even they run a good chance of being caught in the act. The broader impact is that Canada (or any country) can enforce its data privacy laws and maintain control, without an ally (or adversary) bypassing them. For example, Canadian law might say you need a warrant to search data – Scenario 2 ensures that practically, that’s true, because data can’t be fetched by a foreign court alone. Scenario 1 undermines that by allowing foreign warrants to silently reach in.

In conclusion, Scenario 1 is high-risk for sovereignty and covert data exposure, suitable perhaps for low sensitivity environments or those willing to trust U.S. providers, whereas Scenario 2 is a high-security, high-sovereignty configuration aimed at sensitive data protection, though with higher operational overhead. The trend by October 2025, especially in government and critical industries, is increasingly towards the latter for sensitive workloads, driven by the growing recognition of the CLOUD Act’s implicationsthinkon.comcyberincontext.ca. Canada has been exploring ways to build sovereign cloud services or require contractual assurances (like having data held by a Canadian subsidiary) – but as experts note, even those measures come down to “trusting” that the U.S. company will resist unwarranted orderscyberincontext.ca. Many are no longer comfortable with that trust. Scenario 2 embodies a zero-trust stance not only to hackers but also to vendors and external jurisdictions.

Both scenarios have the shared goal of protecting data, but their philosophies differ: Scenario 1 says “trust the big vendor to do it right (with some risk)”, Scenario 2 says “trust no one but ourselves”. For a red team simulating a state actor, the difference is night and day. In Scenario 1, the red team can operate like a lawful insider, leveraging vendor systems to achieve goals quietly. In Scenario 2, the red team is forced into the role of an external attacker, with all the challenges and chances of exposure that entails. This stark contrast is why the choice of IT architecture is not just an IT decision but a security and sovereignty decision.

Sources: This analysis drew on multiple sources, including Microsoft’s own statements on legal compliance (e.g., Microsoft’s admission that it must comply with U.S. CLOUD Act requests despite foreign lawscyberincontext.ca, and Microsoft’s transparency data on law enforcement demandsmicrosoft.commicrosoft.com), as well as commentary from Canadian government and industry experts on cloud sovereignty risksthinkon.comthinkon.com. Technical details on Intune’s capabilitieslearn.microsoft.com and real-world misuse by threat actorshalcyon.ai illustrate how remote management can be turned into an attack vector. The default escrow of BitLocker keys to Azure AD was noted in forensic analysis literatureblog.elcomsoft.com, reinforcing how vendor ecosystems hold keys to the kingdom. Additionally, examples of telemetry and update control issuesborncity.comborncity.com show that even attempting to disable communications can be challenging – hence the need for strong network enforcement in Scenario 2. All these pieces underpin the conclusion that a fully sovereign setup severely limits silent exfiltration pathways, whereas a cloud-integrated setup inherently creates them.