Canadian Sovereignty threat Exercise: Apple

Scenario Overview

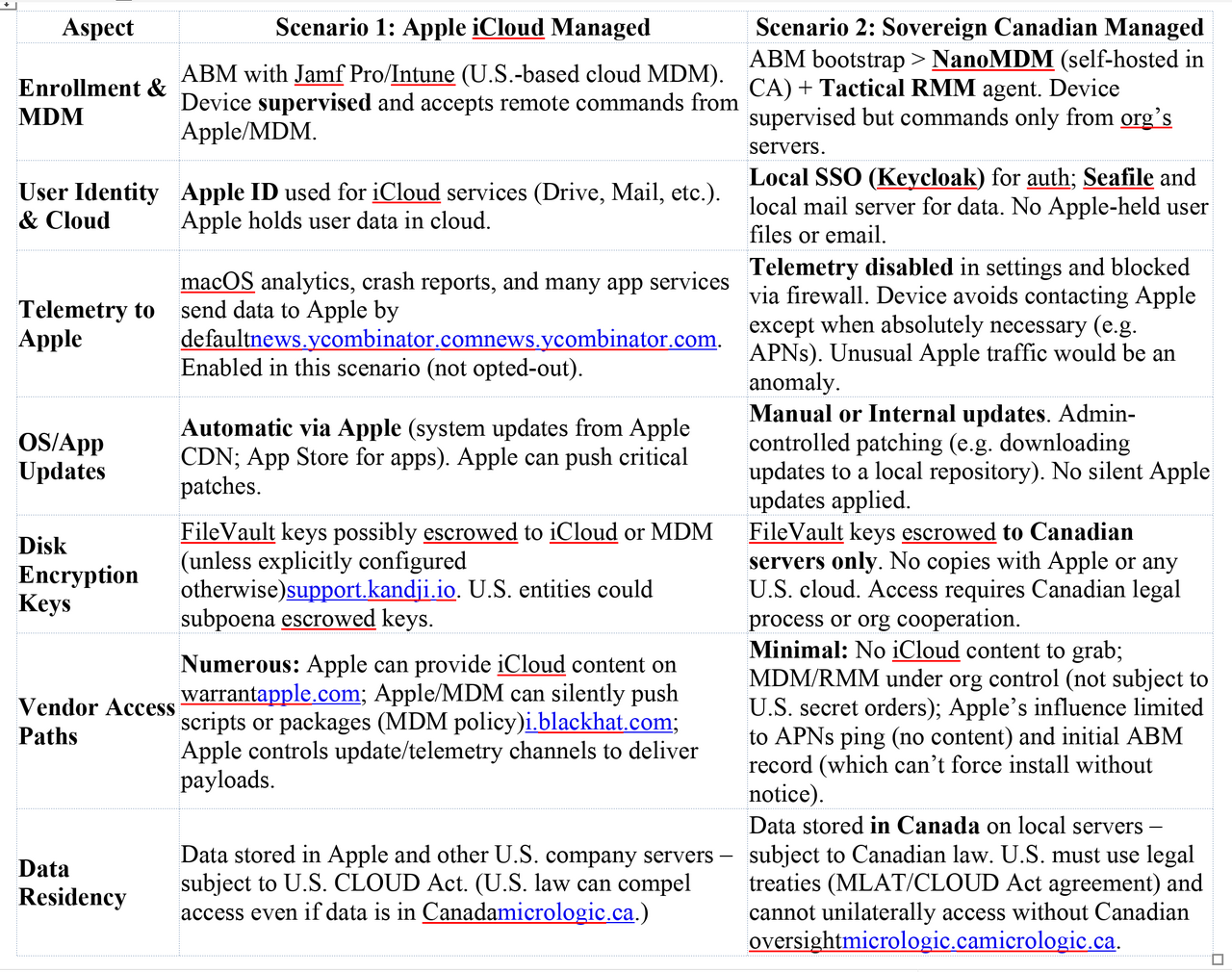

Apple iCloud Workstation (Scenario 1): A fully Apple-integrated macOS device enrolled via Apple Business Manager (ABM) and managed by a U.S.-based MDM (Jamf Pro or Microsoft Intune). The user signs in with an Apple ID, leveraging iCloud Drive for file sync and iCloud Mail for email, alongside default Apple services. Device telemetry/analytics and diagnostics are enabled and sent to Apple. System and app updates flow through Apple’s standard channels (macOS Software Update service and Mac App Store). FileVault disk encryption is enabled, and recovery keys may be escrowed with Apple or the MDM by default (for example, storing the key in iCloud, which Apple does not recommend for enterprise devicessupport.kandji.io).

Fully Sovereign Canadian Workstation (Scenario 2): A data-sovereign macOS device also bootstrapped via Apple Business Manager (for initial setup only) but then managed entirely in-country using self-hosted NanoMDM (open-source Apple MDM server) and Tactical RMM (open-source remote monitoring & management agent) hosted on Canadian soil. The user does not use an Apple ID for any device services; instead, authentication is through a local Keycloak SSO and all cloud services are on-premises (e.g. Seafile for file syncing, and a local Dovecot/Postfix mail server for email). Apple telemetry is disabled or blocked by policy/firewall – no crash reports, Siri/Spotlight analytics, or other “phone-home” diagnostics are sent to Apple’s servers. OS and app updates are handled manually or via a controlled internal repository (no automatic fetching from Apple’s servers). The Mac is FileVault-encrypted with keys escrowed to Canadian infrastructure only, ensuring Apple or other foreign entities have no access to decryption keys.

Telemetry, Update Channels, and Vendor Control

Apple-Facing Telemetry & APIs (Scenario 1): In this environment, numerous background services and update mechanisms communicate with Apple, providing potential vendor-accessible surfaces. By default, macOS sends analytics and diagnostic data to Apple if the user/organization consents. This can include crash reports, kernel panics, app usage metrics, and morenews.ycombinator.com. Even with user opt-outs, many built-in apps and services (Maps, Siri, Spotlight suggestions, etc.) still engage Apple’s servers (e.g. sending device identifiers or queries)news.ycombinator.comnews.ycombinator.com. The Mac regularly checks Apple’s update servers for OS and security updates, and contacts Apple’s App Store for application updates and notarization checks. Because the device is enrolled in ABM and supervised, Apple’s ecosystem has a trusted foothold on the device – the system will accept remote management commands and software delivered via the Apple push notification service (APNs) and signed by Apple or the authorized MDM. Available surfaces exploitable by Apple or its partners in Scenario 1 include:

- Device Analytics & Diagnostics: Detailed crash reports and usage metrics are uploaded to Apple (if not explicitly disabled), which could reveal software inventory, application usage patterns, or even snippets of memory. While intended for quality improvements, these channels could be leveraged under lawful order to glean information or guide an exploit (e.g. identifying an unpatched app). Apple’s own documentation confirms that if users opt-in, Mac analytics may include app crashes, usage, and device detailsnews.ycombinator.com. Many Apple apps also send telemetry by design (e.g. App Store sending device serial numbers)news.ycombinator.com, and such traffic normally blends in as legitimate.

- Apple ID & iCloud Services: Because the user relies on iCloud Drive and Mail, a treasure trove of data resides on Apple’s servers. Under a FISA or CLOUD Act order, Apple can be compelled to quietly hand over content from iCloud accounts (emails, files, backups, device info, etc.) without the user’s knowledgeapple.com. Apple’s law enforcement guidelines state that iCloud content (mail, photos, files, Safari history, etc.) “as it exists in the customer’s account” can be provided in response to a valid search warrantapple.com. In practice, this means much of the user’s data may be directly accessible to U.S. authorities via Apple – an exfiltration path entirely server-side (no device compromise needed). Notably, Apple’s Transparency Reports show regular FISA orders for iCloud contentapple.comapple.com. Because iCloud Mail and Drive in 2025 are not end-to-end encrypted by default for managed devices (Advanced Data Protection is likely disabled or unsupported in corporate contexts), Apple holds the encryption keys and can decrypt that data for lawful requests. Even if data is stored on servers abroad, a U.S.-based company like Apple must comply with U.S. orders due to the CLOUD Actmicrologic.ca. (For instance, Apple’s iCloud mail servers for North America are physically in the U.S.apple.com, putting Canadian user emails fully under U.S. jurisdiction.)

- MDM and Update Mechanisms: The presence of a third-party MDM (Jamf or Intune) introduces another vendor with potential access. Jamf Pro, for example, has the ability to push scripts or packages to enrolled Macs and execute them silently with root privilegesi.blackhat.com. Red teamers have demonstrated using Jamf’s policy and scripting features to run malicious code on endpoints (“scripts can be bash, python, etc., run as root by default”i.blackhat.com). Under a secret court order, Apple or law enforcement could compel the cloud MDM provider (Jamf Cloud or Microsoft, in the case of Intune) to deploy an exfiltration payload to the target Mac. Because the device trusts the MDM’s instructions (it’s a managed device), such payloads would execute as an authorized action – e.g. a script to zip up user files/emails and send to an external server could be pushed without user interaction. This is a highly feasible one-time exfiltration vector in Scenario 1. If the MDM is cloud-hosted in the U.S., it falls under U.S. legal jurisdiction as well. Even if the MDM is self-hosted by the organization, Apple’s ABM supervision still allows some Apple-mediated control (for instance, APNs will notify devices of MDM commands, and ABM could be used to reassign the device to a different MDM if the device is reset or forced to re-enroll).

- OS Update/Software Supply Chain: Because macOS in Scenario 1 regularly checks in with Apple’s update servers, there’s a theoretical “update injection” path. Apple could, in cooperation with authorities, push a targeted malicious update or configuration to this specific device (for example, a modified macOS Rapid Security Response patch or a fake app update). Since Apple’s software updates are signed and trusted by the device, a targeted update that appears legitimate would be installed quietly. Apple does not publicly do one-off custom updates, but under a lawful secret order, it’s within the realm of possibility (akin to how some state actors consider supply-chain attacks). Even short of a custom OS update, Apple’s existing frameworks like XProtect or MRT (Malware Removal Tool) receive silent signature updates – a coercion scenario could abuse those channels to push a one-time implant (e.g. flag a benign internal tool as “malicious” and replace it via MRT, though this is speculative). The key point is that in Scenario 1 the device is listening regularly to Apple infrastructure for instructions (updates, notarization checks, etc.), so a cooperating vendor has multiple avenues to deliver something unusual with a valid signature.

Sovereign Controls (Scenario 2): In the Canadian-sovereign setup, most of the above channels are shut off or localized, drastically reducing Apple (or U.S. vendor) surfaces:

- No Apple ID / iCloud: The absence of an Apple ID login means iCloud services are not in use. There is no iCloud Drive sync or mail on Apple servers to target. All user files remain on the device or in the local Seafile server, and email resides on a Canadian mail server. This removes the straightforward server-side grab of data that exists in Scenario 1. Apple cannot hand over what it doesn’t have. Any attempt by U.S. agencies to get user data would have to go through Canadian service providers or the organization itself via legal channels, rather than quietly through Apple’s backdoor.

- Disabled Telemetry: The Mac in Scenario 2 is configured (via MDM profiles and network firewall rules) to block or disable Apple telemetry endpoints. Crash reporting, analytics, and services like Siri/Spotlight network queries are turned off at the OS level (system settings) and further enforced by blocking Apple telemetry domains. This means the Mac will not routinely talk to Apple’s servers for background reporting. While some low-level processes like Gatekeeper’s notarization checks or OCSP might still attempt connections, a hardened sovereign config may route those checks through a proxy or allow only whitelisted Apple domains. The key is that any unexpected communication to Apple would be anomalous and likely blocked or flagged. (It’s known that simply opting out via settings may not catch all Apple trafficnews.ycombinator.com, so Scenario 2 likely uses host-based firewalls like Little Snitch/LuLu or network firewalls to enforce no-contact. In fact, experts note that macOS has many built-in telemetry points that require blocking at the network layer if you truly want zero-contactnews.ycombinator.com.) As a result, Apple loses visibility into the device’s status and cannot exploit diagnostics or analytics channels to insert commands – those channels are effectively closed.

- Local Update Management: Software updates are not automatically pulled from Apple. The organization might maintain an internal update server or simply apply updates manually after vetting. This prevents Apple from directly pushing any update without the organization noticing. The device isn’t checking Apple’s servers on its own; an admin would retrieve updates (possibly downloading standalone packages from Apple on a controlled network and distributing them). There’s no “zero-day” silent patch deployment from Apple in this model. Even App Store apps might be avoided in favor of direct software installs or an internal app repository (e.g. Homebrew or Munki packages), further cutting off Apple’s injection path. In short, the update supply chain is under the organization’s control in Scenario 2.

- MDM & RMM in Canadian Control: The device is still enrolled in MDM (since ABM was used for initial deployment, the Mac is supervised), but NanoMDM is the MDM server and it’s self-hosted in Canada. NanoMDM is a minimalist open-source MDM that handles core device management (enrollments, command queueing via APNs, etc.) but is run by the organization itselfmicromdm.io. There is no third-party cloud in the loop for device management commands – all MDM instructions come from the org’s own server. Similarly, Tactical RMM provides remote management (monitoring, scripting, remote shell) via an agent, but this too is self-managed on local infrastructure. Because these tools are under the organization’s jurisdiction, U.S. agencies cannot directly compel them in the dark. Any lawful request for assistance would have to go through Canadian authorities and ultimately involve the organization’s cooperation (which by design is not given lightly in a sovereignty-focused setup). Apple’s ABM involvement is limited to the initial enrollment handshake. After that, Apple’s role is mostly just routing APNs notifications for MDM, which are encrypted and tied to the org’s certificates. Unlike Scenario 1’s Jamf/Intune, here there is no American cloud company with master access to push device commands; the master access lies with the organization’s IT/SOC team.

- Apple Push & Device Enrollment Constraints: One might ask, could Apple still leverage the ABM/DEP connection? In theory, Apple could change the device’s MDM assignment in ABM or use the profiles command to force re-enrollment to a rogue MDM (Apple has added workflows to migrate devices between MDMs via ABM without wipingsupport.apple.comsupport.apple.com). However, in macOS 14+, forcing a new enrollment via ABM prompts the user with a full-screen notice to enroll or wipe the devicesupport.apple.com – highly conspicuous and not a silent action. Since Scenario 2’s admins have likely blocked any such surprise with firewall or by not allowing automatic re-enrollment prompts, this path is not practical for covert exfiltration. Likewise, Apple’s push notification service (APNs) is required for MDM, but APNs on its own cannot execute commands; it merely notifies the Mac to check in with its known MDM servermicromdm.io. Apple cannot redirect those notifications to another server without re-enrollment, and it cannot read or alter the content of MDM commands (which are mutually authenticated between device and NanoMDM). Thus, the APNs channel is not an exploitable vector for code injection in Scenario 2 – it’s essentially a ping mechanism.

Summary of Vendor-Controlled Surfaces: Below is a side-by-side comparison of key control/telemetry differences:

Feasible Exfiltration Strategies Under Lawful Vendor Cooperation

Under a lawful FISA or CLOUD Act scenario, a “red team” (as a stand-in for a state actor with legal leverage) might attempt covert one-time extraction of files, emails, and synced data. The goal: get in, grab data, get out without tipping off the user or local SOC, and without leaving malware behind. We analyze how this could be done in each scenario given the available vendor cooperation.

Scenario 1 (Apple-Integrated) – Potential Exfiltration Paths:

Server-Side Data Dump (No Endpoint Touch): The simplest and stealthiest method is leveraging Apple’s access to cloud data. Apple can be compelled to export the user’s iCloud data from its servers. This includes iCloud Mail content, iCloud Drive files, iOS device backups (if the user’s iPhone is also in the ecosystem), notes, contacts, calendars, and so onapple.comapple.com. Because the user in Scenario 1 relies on these services, a large portion of their sensitive data may already reside in Apple’s cloud. For example, if “Desktop & Documents” folders are synced to iCloud Drive (a common macOS setting), nearly all user files are in Apple’s data centers. Apple turning over this data to law enforcement would be entirely invisible to the user – it’s a server transaction that doesn’t involve the Mac at all. Detection risk: Virtually none on the endpoint; the user’s Mac sees no unusual activity. The organization’s SOC also likely has zero visibility into Apple’s backend. (Apple’s policy is not to notify users of national security data requestspadilla.senate.gov, and such requests come with gag orders, so neither the user nor admins would know.) Limitations: This only covers data already in iCloud. If the user has files stored locally that are not synced, or uses third-party apps, those wouldn’t be obtained this way. Also, end-to-end encrypted categories (if any are enabled) like iCloud Keychain or (with Advanced Data Protection on) iCloud Drive would not be accessible to Apple – but in typical managed setups ADP is off, and keychain/passwords aren’t the target here.

MDM-Orchestrated Endpoint Exfiltration: For any data on the Mac itself (or in non-Apple apps) that isn’t already in iCloud, the red team could use the MDM channel via the vendor’s cooperation. As noted, Jamf or Intune can remotely execute code on managed Macs with high privilegesi.blackhat.com. Under lawful order, the MDM operator could deploy a one-time exfiltration script or package to the target Mac. For instance, a script could recursively collect files from the user’s home directory (and any mounted cloud drives), as well as export Mail.app local messages, then send these to an external drop point (or even back up to a hidden location in the user’s iCloud, if accessible, to piggyback on existing traffic). Because this action is happening under the guise of MDM, it uses the device’s built-in management agent (e.g., the Jamf binary, running as root). This is covert in the sense that the user gets no prompt – it’s normal device management activity. If Intune is used, a similar mechanism exists via Intune’s shell script deployment for macOS or a “managed device action.” The payload could also utilize macOS’s native tools (like scp/curl for data transfer) to avoid dropping any new binary on disk. Detection risk: Low to moderate. From the device side, an EDR (Endpoint Detection & Response) agent might flag unusual process behavior (e.g. a script compressing files and sending data out). However, the script could be crafted to use common processes and network ports (HTTPS to a trusted cloud) to blend in. Jamf logs would show that a policy ran, but typically only Jamf admins see those logs. If the MDM vendor is acting secretly (perhaps injecting a script run into the Jamf console without the organization’s knowledge), the org’s IT might not catch it unless they specifically audit policy histories. This is a plausible deniability angle – since Jamf/Intune have legitimate admin access, any data exfil might be viewed as an approved IT task if noticed. The local SOC would need to be actively hunting for anomalies in device behavior to catch it (e.g. sudden outgoing traffic spike or a script process that isn’t normally run). Without strong endpoint monitoring, this could sail under the radar.

Apple Update/Provisioning Attack: Another vector is using Apple’s control over software distribution. For example, Apple could push a malicious app or update that the user installs, which then exfiltrates data. One subtle method: using the Mac App Store. With an Apple ID, the user might install apps from the App Store. Apple could introduce a trojanized update to a common app (for that user only, via Apple ID targeting) or temporarily remove notarization checks for a malicious app to run. However, this is riskier and more likely to be noticed (it requires the user to take some action like installing an app or might leave a new app icon visible). A more targeted approach: Apple’s MDM protocol has a feature to install profiles or packages silently. Apple could coordinate with the MDM to push a new configuration profile that, say, enables a hidden remote access or turns on additional logging. Or push a signed pkg that contains a one-time agent which exfiltrates data then self-deletes. Since the device will trust software signed by Apple’s developer certificates (or enterprise cert trusted via MDM profile), this attack can succeed if the user’s system doesn’t have other restrictions. Detection risk: Moderate. An unexpected configuration profile might be noticed by a savvy user (they’d see it in System Settings > Profiles), but attackers could name it innocuously (e.g. “ macOS Security Update #5”) to blend in. A temporary app or agent might trigger an antivirus/EDR if its behavior is suspicious, but if it uses system APIs to copy files and send network traffic, it could pass as normal. Modern EDRs might still catch unusual enumeration or large data exfil, so the success here depends on the target’s security maturity.

Leveraging iCloud Continuity: If direct device access was needed but without using MDM, Apple could also use the user’s Apple ID session. For example, a lesser-known vector: the iCloud ecosystem allows access to certain data via web or APIs. Apple (with a warrant) could access the user’s iCloud Photos, Notes, or even use the Find My system to get device location (though that’s more surveillance than data theft). These aren’t exfiltrating new data from the device per se, just reading what’s already synced. Another trick: If the user’s Mac is signed into iCloud, Apple could potentially use the “Find My Mac – play sound or message” feature or push a remote lock/wipe. Those are destructive and not useful for covert exfiltration (and would absolutely be detected by the user), so likely not considered here except as a last resort (e.g. to sabotage device after exfil).

In summary, Scenario 1 is rich with covert exfiltration options. Apple or the MDM provider can leverage built-in trust channels (iCloud, MDM, update service) to retrieve data or run code, all under the guise of normal operation. The user’s reliance on U.S.-controlled infrastructure means a lawful order to those providers can achieve the objective without the user’s consent or knowledge.

Scenario 2 (Sovereign Setup) – Potential Exfiltration Paths:

In Scenario 2, the usual “easy” buttons are mostly gone. Apple cannot simply download iCloud data (there is none on their servers), and they cannot silently push code via Jamf/Intune (the MDM is controlled by the organization in Canada). The red team must find alternative strategies:

Canadian Legal Cooperation or Warrant: Since the device and its services are all under Canadian control, a lawful approach would be to go through Canadian authorities – essentially using MLAT (Mutual Legal Assistance) or CLOUD Act agreements (if any) to have Canada serve a warrant on the organization for the data. This is no longer covert or strictly a red-team tactic; it becomes an overt legal process where the organization would be alerted (and could contest or at least is aware). The spirit of the scenario suggests the adversary wants to avoid detection, so this straightforward legal route defeats the purpose of stealth. Therefore, we consider more covert vendor cooperation workarounds below (which border on active intrusion since no willing vendor exists in the U.S. to assist).

Apple’s Limited Device Access: Apple’s only touchpoint with the Mac is ABM/APNs. As discussed, forcing a re-enrollment via ABM would alert the user (full-screen prompts)support.apple.com, so that’s not covert. Apple’s telemetry is blocked, so they can’t even gather intel from crash reports or analytics to aid an attack. Software updates present a narrow window: if the user eventually installs a macOS update from Apple, that is a moment Apple-signed code runs. One could imagine an intelligence agency attempting to backdoor a macOS update generally, but that would affect all users – unlikely. A more targeted idea: if Apple knows this specific device (serial number) is of interest, they could try to craft an update or App Store item that only triggers a payload on that serial or for that user. This is very complex and risky, and if discovered, would be a huge scandal. Apple historically refuses to weaken its software integrity for law enforcement (e.g. the Apple–FBI case of 2016 over iPhone unlockingen.wikipedia.org), and doing so for one Mac under secrecy is even more far-fetched. In a theoretical extreme, Apple could comply with a secret order by customizing the next minor update for this Mac’s model to include a data collection agent, but given Scenario 2’s manual update policy, the organization might vet the update files (diffing them against known good) before deployment, catching the tampering. Detection risk: Extremely high if attempted, as it would likely affect the software’s cryptographic signature or behavior noticeably. Thus, this path is more hypothetical than practical.

Compromise of Self-Hosted Tools (Supply Chain Attack): With no willing vendor able to assist, an attacker might attempt to compromise the organization’s own infrastructure. For instance, could they infiltrate the NanoMDM or Tactical RMM servers via the software supply chain or zero-day exploits? If, say, the version of Tactical RMM in use had a backdoor or the updater for it was compromised, a foreign actor could silently gain a foothold. Once in, they could use the RMM to run the same sort of exfiltration script as in Scenario 1. However, this is no longer “lawful cooperation” – it becomes a hacking operation. It would also be quite targeted and difficult, and detection risk depends on the sophistication: a supply chain backdoor might go unnoticed for a while, but any direct intrusion into the servers could trigger alerts. Given that Scenario 2’s premise is a strongly secured environment (likely with a vigilant SOC), a breach of their internal MDM/RMM would be high risk. Nonetheless, from a red-team perspective, this is a potential vector: If an attacker cannot get Apple or Microsoft to help, they might target the less mature open-source tools. E.g., Tactical RMM’s agent could be trojanized to exfil data on next update – but since Tactical is self-hosted, the org controls updates. Unless the attacker compromised the project supply (which would then hit many users, again noisy) or the specific instance, it’s not trivial.

Endpoint Exploits (Forced by Vendor): Apple or others might try to use an exploit under the guise of normal traffic. For example, abuse APNs: Apple generally can’t send arbitrary code via APNs, but perhaps a push notification could be crafted to exploit a vulnerability in the device’s APNs client. This again veers into hacking, not cooperation. Similarly, if the Mac uses any Apple online service (maybe the user still uses Safari and it contacts iCloud for safe browsing, etc.), Apple could theoretically inject malicious content if compelled. These are highly speculative and not known tactics, and they carry significant risk of detection or failure (modern macOS has strong security against code injection).

In summary, Scenario 2 offers very limited avenues for covert exfiltration via vendor cooperation – essentially, there is no friendly vendor in the loop who can be quietly compelled to act. Apple’s influence has been minimized to the point that any action on their part would likely alert the user or fail. The contrast with Scenario 1 is stark: what was easy and silent via cloud/MDM in the first scenario becomes nearly impossible without tipping someone off in the second.

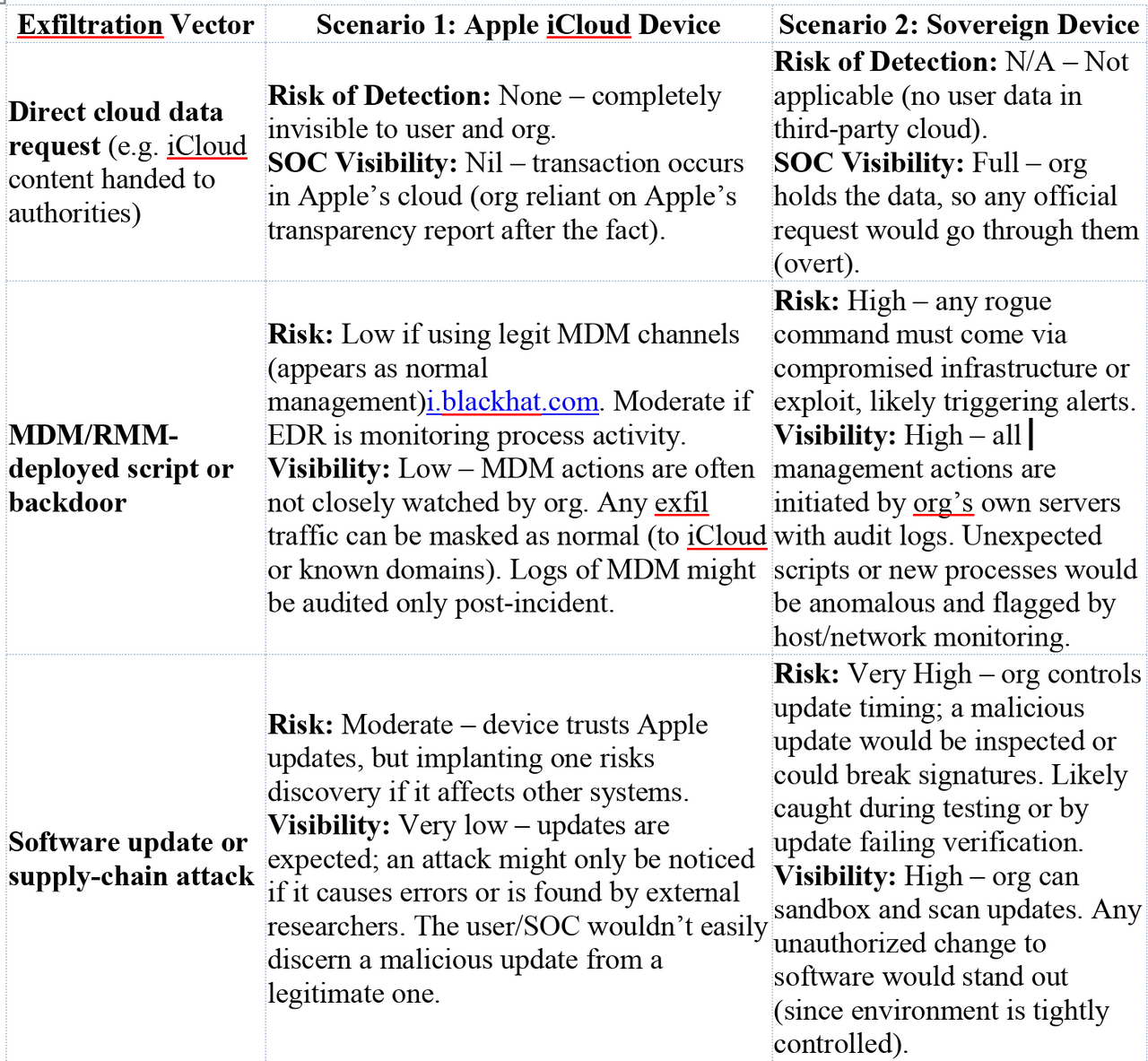

Detection Vectors and SOC Visibility

From a defensive viewpoint, the two scenarios offer different visibility to a local Security Operations Center (SOC) or IT security team, especially in a public-sector context where audit and oversight are critical.

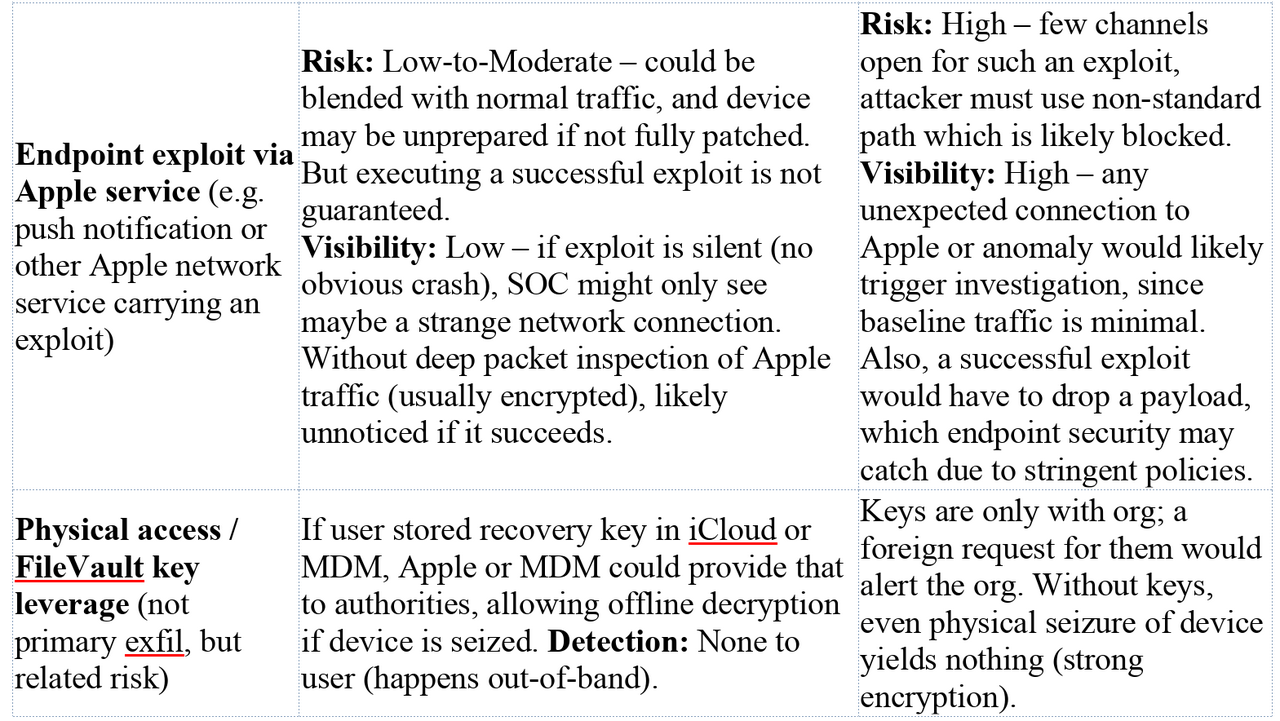

- In Scenario 1 (Apple-managed): Many of the potential exfiltration actions would be hard to distinguish from normal traffic or admin activity. For example, if Apple extracts iCloud data, that occurs entirely in Apple’s cloud – the organization’s SOC never sees it. If an MDM script runs on the Mac to exfiltrate data, it will appear as the normal MDM agent process doing work, which is routine on managed Macs. Unless the SOC has advanced EDR telemetry on endpoints, they might not log every script executed by the trusted Jamf agent. Network-wise, if the script sends files to an external server, a network monitoring tool might catch unusual large outbound transfers. However, a clever attacker could send data to an Apple-owned domain (i.e. piggyback on iCloud) or another whitelisted cloud service, so it blends with normal traffic. For instance, uploading the payload to the user’s own iCloud Drive (as a stash) would appear as standard iCloud sync traffic, likely ignored by DLP systems since it’s user-approved cloud storage. Another detection angle is Jamf/Intune logs – if the organization regularly reviews their MDM logs, they might spot an unexpected policy or command executed on that device at an odd time. But not all orgs do that level of auditing, and a state actor with access to MDM might also try to clean up logs or use built-in scripting features that don’t obviously log every command content. (Jamf might log that a script ran, but not necessarily echo all script contents to a central log visible to admins, depending on configuration.)

- Additionally, device telemetry in Scenario 1 largely bypasses the organization. Apple gets a lot of diagnostics (if enabled) that the org doesn’t. The org’s SOC would not see, for example, a detailed crash report that was sent to Apple containing clues of compromise. Apple might see it, but under a secret order, Apple isn’t going to warn the target. This asymmetry means the SOC could be blind to certain events. Public sector orgs often rely on macOS native logging and any installed EDR/SIEM agents for visibility. If the red team’s exfiltration is done using Apple-signed processes, it might not trigger any known malware signatures. It becomes a needle-in-haystack situation to detect a well-crafted insider attack by the device’s own management systems.

- Detection Risk Level – Scenario 1: From the attacker’s perspective, the risk of detection is low if they stick to server-side exfiltration (completely invisible on endpoint). It’s low-to-moderate if using MDM scripting, largely depending on the organization’s endpoint monitoring rigor. A mature SOC with EDR might catch anomalies (e.g., a script compressing files, or a sudden process spawning tar and curl). But if this is a high-value target, the adversary might assume strong monitoring and perhaps use more subtle means (like trickling data out via iCloud over time). Overall, scenario 1 favors the attacker’s stealth.

- In Scenario 2 (Sovereign): Here, the organization holds the keys to management and thus has far greater visibility. All MDM commands come from their NanoMDM server – so they can log and review every command that was sent. If an outsider somehow tried to inject an MDM command, it would either fail or be logged plainly. The Tactical RMM agent similarly logs actions and is under the SOC’s monitoring (and as a precaution, the org could enforce 2FA and auditing on RMM usage, so any rogue session is noticed). No Apple or third-party cloud is doing things behind their back. Therefore, any unusual activity on the device is more likely to stand out. For instance, the Mac should rarely, if ever, initiate connections to Apple (aside from perhaps checking notarization or time server). If the Mac suddenly tries to contact an Apple update server or some unfamiliar cloud, the network monitoring can flag that, because it’s not normal for this locked-down host. The absence of routine Apple telemetry ironically makes it easier to catch anomalies – there’s a low baseline of “expected” external communication. The SOC might be ingesting logs from the host-based firewall, showing if any process tries to bypass and contact disallowed domains.

- Moreover, user data is internal – so if exfiltration were to occur, it likely has to go out over the network to an external server. The SOC likely has egress filters and alerts on large data exports or unknown destinations. They might even whitelist all known good services and block others (a common practice in secure government networks). So an attacker can’t rely on blending with iCloud or Google traffic; those might be outright blocked or closely scrutinized. Example: If a compromised process tries to send archive files to a foreign server, it might trip an alert or be blocked by a next-gen firewall or DLP system, especially if not using an approved proxy.

- Local logging/audit: In Scenario 2, the endpoints likely have more aggressive logging (because it’s under org control and not offloaded to Apple’s cloud). The SOC could be using macOS’s unified logging, or tools like OpenBSM audit, OSQuery, or other agents to record process executions, file access, etc. Public sector deployments often require strict audit trails. Thus, any malicious implant or script would leave breadcrumbs that skilled defenders could find after the fact (if not in real-time).

- Detection Risk Level – Scenario 2: From an attacker’s view, the risk of detection is high. Without a cooperative vector, any attempt likely involves exploiting something, which tends to be noisier and more likely to crash or be caught. Even a supply-chain backdoor in an update would likely be noticed due to extra scrutiny in these environments. The very measures that ensure sovereignty (no silent outsider access) are the same that raise the alarm bells when something does go wrong. In essence, Scenario 2 is designed so that any access to data must go through the front door, where guards are watching.

Risks, Limitations, and Sovereignty Impacts

Finally, we assess the broader risks and sovereignty implications of each setup, with some context for Canadian public-sector use:

- Scenario 1 – Risks & Sovereignty Trade-offs: This conventional setup offers convenience and seamless integration at the cost of sovereignty and security risk. All critical services depend on infrastructure controlled by foreign entities (Apple, possibly Microsoft). As experts have pointed out, Canadian data in U.S. company clouds is subject to foreign laws like the CLOUD Act, meaning Canada “cannot ensure full sovereignty” over that datamicrologic.ca. The risk isn’t just theoretical: U.S. authorities can and do request data from tech companies; Apple’s own reports confirm responding to thousands of such requests every yearapple.comapple.com. For a Canadian government department or any organization handling sensitive citizen data, this is a glaring vulnerability – data could be accessed by a foreign government without Canadian consent or even awareness. Pierre Trudel (UdeM professor) noted that relying on companies under foreign jurisdiction “undermines our national security and exposes [us] to risks of foreign interference”, urging efforts to regain digital sovereigntymicrologic.camicrologic.ca. From a red-team perspective, Scenario 1 is a target-rich environment: multiple avenues exist to carry out a lawful intercept or covert extraction with minimal risk of exposure. The limitation of this scenario is the implicit trust on third parties. If any one of them is compromised or compelled, the organization has little recourse. On the other hand, IT staff and users may find this setup easiest to use – things like iCloud syncing and automatic updates improve productivity and user experience. It’s a classic security vs. convenience trade-off. There’s also a risk of complacency: because so much is handled by Apple, organizations might not implement their own rigorous monitoring, creating blind spots (assuming Apple’s ecosystem is “secure by default”, which doesn’t account for insider threat or lawful access scenarios).

- Scenario 2 – Benefits & Challenges: The sovereign approach dramatically reduces dependency on foreign providers, thereby mitigating the Cloud Act risk and reinforcing data residency. All data and keys remain under Canadian control; any access by an outside entity would require Canadian legal oversight or overt cooperation. This aligns with recommendations for a “Canadian sovereign cloud for sensitive data” and prioritizing local providersmicrologic.ca. Security-wise, it shrinks the attack surface – Apple can’t easily introduce backdoors, and U.S. agencies can’t quietly reach in without breaking laws. However, this scenario comes with operational challenges. The organization must maintain complex infrastructure (SSO, file cloud, MDM, RMM, patch management) largely on its own. That demands skilled staff and investment. Updates handled manually could lag, potentially leaving systems vulnerable longer – a risk if threat actors exploit unpatched flaws. User convenience might suffer; for example, no Apple ID means services like FaceTime or iMessage might not work with their account on Mac, or the user might need separate apps for things that iCloud handled automatically. Another limitation is that NanoMDM (and similar open tools) might not have full feature parity with commercial MDMs – some automation or profiles might be missing, though NanoMDM focuses on core needsmicromdm.io. Similarly, Tactical RMM and Seafile must be as secure as their commercial counterparts; any misconfiguration could introduce new vulnerabilities (the org essentially becomes its own cloud provider and must practice good “cloud hygiene”).

- In terms of detection and audit, Scenario 2 shines: it inherently creates an environment where local SOC visibility is maximized. All logs and telemetry stay within reach of the security team. This fosters a culture of thorough monitoring – likely necessary given the lack of third-party support. For public sector bodies, this also means compliance with data residency regulations (e.g. some Canadian provinces require certain data to stay in Canada, which Scenario 2 satisfies by design). The sovereignty impact is that the organization is far less exposed to foreign government orders. It takes a stance that even if an ally (like the U.S.) wants data under FISA, they cannot get it without Canada’s legal process. This could protect citizens’ privacy and national secrets from extraterritorial reach, which in a geopolitical sense is quite significantmicrologic.camicrologic.ca. On the flip side, if Canadian authorities themselves need the data (for domestic investigation), they can get it through normal warrants – that doesn’t change, except it ensures the chain of custody stays in-country.

Tooling References & Modern Capabilities (Oct 2025): The playbook reflects current tooling and OS features:

- Apple’s ecosystem now includes features like Rapid Security Response (RSR) updates for macOS, which can be pushed quickly – Scenario 1 devices will get these automatically, which is a potential injection point, whereas Scenario 2 devices might only apply them after vetting. Apple has also deployed improved device attestation for MDM (to ensure a device isn’t fake when enrolling). Scenario 1 likely partakes in attestation via Apple’s servers, while Scenario 2 might choose not to use that feature (to avoid reliance on Apple verifying device health).

- EDR and logging tools in 2025 (e.g. Microsoft Defender for Endpoint on Mac, CrowdStrike, open-source OSQuery) are commonplace in enterprises. In Scenario 1, if such a tool is present, it could theoretically detect malicious use of MDM or unusual processes – unless the tool is configured to trust MDM actions. In Scenario 2, the same tools would be leveraged, but tuned to the environment (for instance, alert on any Apple connection since there shouldn’t be many).

- FileVault escrow differences are notable: in Scenario 1, many orgs use either iCloud or their MDM to escrow recovery keys for lost password scenarios. If iCloud was used, Apple could provide that key under court order, allowing decryption of the Mac if physical access is obtained (the FBI’s traditional request). In Scenario 2, escrow is to a Canadian server (perhaps integrated with Keycloak or an internal database). That key is inaccessible to Apple, meaning even if the Mac was seized at the border, U.S. agents couldn’t get in without asking the org (or brute-forcing, which is unviable with strong encryption).

- Tactical RMM and NanoMDM are highlighted as emerging open technologies enabling this sovereign model. Tactical RMM’s self-hosted agent gives the org remote control similar to commercial RMMs but without cloud dependencies. It supports Windows/macOS/Linux via a Go-based agentreddit.com and can be made compliant with privacy laws since data storage is self-manageddocs.tacticalrmm.com. NanoMDM is lightweight but sufficient for pushing configs and receiving device info; it lacks a friendly GUI but pairs with other tools if needed. The use of Keycloak for SSO on Mac suggests possibly using Apple’s enterprise SSO extension or a Kerberos plugin so that user login is tied to Keycloak credentials – meaning even user authentication doesn’t rely on Apple IDs at all (no token sharing with Apple’s identity services). This keeps identity data internal and possibly allows integration with smartcards or 2FA for login, which public sector often requires.

Side-by-Side Risk & Visibility Comparison

To encapsulate the differences, the table below assigns a qualitative Detection Risk Level and notes SOC Visibility aspects for key attack vectors in each scenario:

Canadian Data Residency & Sovereignty: In essence, Scenario 2 is built to enforce Canadian data residency and blunt extraterritorial legal reach. As a result, it significantly reduces the risk of a silent data grab under U.S. FISA/CLOUD Act authority. Scenario 1, by contrast, effectively places Canadian data within reach of U.S. jurisdiction through the involved service providers. This is why Canadian government strategists advocate for sovereign clouds and control over sensitive infrastructure: “All of our resources should be focused on regaining our digital sovereignty… Our safety as a country depends on it.”micrologic.ca. The trade-off is that with sovereignty comes responsibility – the need to maintain and secure those systems internally.

Conclusion

Scenario 1 (Apple iCloud Workstation) offers seamless integration but at the cost of giving Apple (and by extension, U.S. agencies) multiple covert avenues to access or exfiltrate data. Telemetry, cloud services, and remote management are double-edged swords: they improve user experience and IT administration, but also provide channels that a red team operating under secret legal orders can quietly exploit. Detection in this scenario is difficult because the attacks abuse trusted Apple/MDM functionality and blend with normal operations. For an adversary with lawful access, it’s a target ripe for the picking, and for a defender, it’s a scenario where you are often blindly trusting the vendor.

Scenario 2 (Fully Sovereign Workstation) drastically limits those avenues, embodying a zero-trust approach to vendor infrastructure. By keeping the device mostly self-contained (no routine calls home to Apple) and all services in-country, it forces any would-be data extraction to go through the organization’s own gateways – where it can ideally be detected or stopped. This setup aligns with Canada’s push for digital sovereignty and protection against foreign interferencemicrologic.camicrologic.ca. The security team has much greater visibility and control, but also a greater burden of maintenance and vigilance. In a red-team simulation, Scenario 2 would frustrate attempts at undetected exfiltration; it might require the “attacker” to switch to more overt or risky methods, which stray outside the bounds of silent lawful cooperation.

In summary: The Apple iCloud scenario is high-risk from a sovereignty perspective – it’s like living in a house with backdoors you can’t lock, hoping nobody with a master key uses them. The Sovereign Canadian scenario is more like a well-fortified compound – fewer backdoors, but you must guard the front and maintain the walls yourself. Each approach has implications for security monitoring, incident response, and legal exposure. As of October 2025, with increasing emphasis on data residency, the trend (especially for public sector) is toward architectures that resemble Scenario 2, despite the added effort, because the cost of silent compromise is simply too high in an environment where you might never know it happened until it’s too latemicrologic.camicrologic.ca.

Sources: The analysis integrates information from Apple’s security and legal documentation (on iCloud data disclosureapple.com, device management capabilitiesi.blackhat.com, and telemetry behaviornews.ycombinator.com), as well as expert commentary on the CLOUD Act and digital sovereignty implications for Canadian datamicrologic.camicrologic.ca. All technical claims about MDM/RMM capabilities and Apple services are backed by these sources and industry knowledge as of late 2025.