Surveillance and Suppression – The new normal?

The following post caught my attention:

https://www.techpolicy.press/the-internet-coup-is-here-and-the-world-is-still-asleep/

I decided to ask chatGPT to do some deep research for me:

Here is the final take:

ChatGPT said:

Executive Summary

Context

The global internet is at an inflection point. Authoritarian states are exporting turnkey censorship and surveillance infrastructure, while democracies are adopting parallel measures under the banners of security, safety, and stability. These two vectors—authoritarian export and democratic creep—are converging on a common outcome: an internet increasingly structured for control rather than freedom.

Key Findings

1. Authoritarian Export of Censorship Tools

- China, via firms like Geedge Networks, is exporting “Great Firewall in a box” solutions to governments in Kazakhstan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and others.

- These systems enable deep packet inspection, VPN blocking, throttling, real-time monitoring, and targeted filtering.

- Western firms are complicit through components, software licenses, and supply chains embedded in these systems.

- Once deployed, such systems are difficult to dismantle, creating structural path dependence.

2. Democratic Drift Toward Surveillance and Control

- United States: Mass surveillance persists (FISA Sec. 702), while bills like the EARN IT Act and local programs (e.g., NYPD’s use of public housing broadband for live CCTV feeds) normalize broad monitoring and content control.

- Canada: Federal and provincial police have quietly used spyware tools for years without modern legal oversight. Privacy protections enshrined in law are lagging behind technology, eroding a legacy of strong civil liberties.

- United Kingdom: The Online Safety Act mandates broad content monitoring, weakens encryption, and creates a “blueprint for repression” justified under safety. Coupled with the Investigatory Powers Act, the UK has embraced state-driven speech regulation.

- Australia: Pioneered laws forcing companies to weaken encryption (TOLA 2018) and granting police powers to hack, impersonate users, and disrupt data (Identify and Disrupt Act 2021). Officials explicitly argue that “privacy is important but not absolute.”

- European Union: The Chat Control proposal, backed by 19 member states, would mandate scanning of all private messages, including encrypted ones, and impose mandatory age verification. Alongside the Digital Services Act and national laws (e.g., Germany’s NetzDG), Europe is embedding systemic content control.

3. Convergence of Authoritarian and Democratic Models

- Though arising from different narratives—authoritarian stability vs. democratic safety/security—both models rely on the same technical infrastructure: DPI, monitoring, weakened encryption, mandatory scanning.

- The risk is a global baseline shift where surveillance-by-default becomes normal, and the distinction between democratic and authoritarian internet governance erodes.

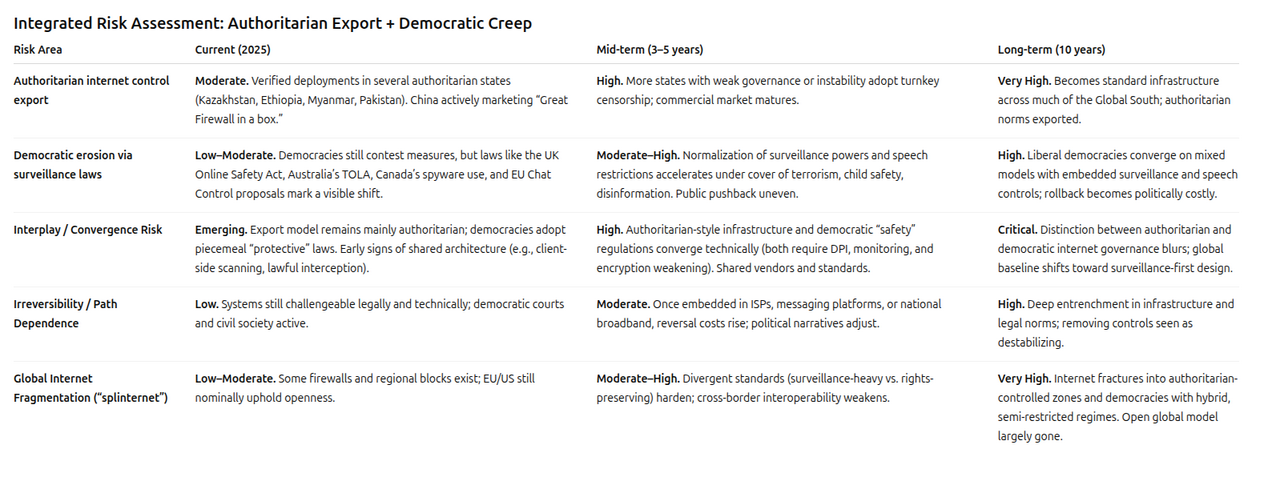

4. Risk Trajectory

- Current (2025): Moderate. Exported systems in select authoritarian states; democracies experimenting with surveillance laws.

- Mid-term (3–5 years): High. Wider adoption by unstable states; democracies normalize censorship and interception. Shared technical standards emerge.

- Long-term (10 years): Critical. Internet fractures into zones of restricted flow. Even democracies operate with embedded surveillance and speech controls. The open, global internet becomes the exception, not the norm.

5. Specific Implications for Democracies

- Canada: Must guard against “lawful interception creep” undermining FIPPA compliance and sovereignty. Vendors risk supply-chain entanglement with censorship infrastructure.

- United States: Ongoing pressure to weaken encryption and expand law enforcement access threatens both civil liberties and the competitiveness of US tech.

- UK, Australia, EU: Already moving toward statutory surveillance regimes, setting precedents that others may follow.

Conclusion

The “internet coup” metaphor is rhetorically strong but directionally accurate. The open, interoperable internet is under structural threat from two converging dynamics: authoritarian export of censorship technologies and democratic normalization of surveillance-first policies. If unchecked, these forces will redefine the internet as an infrastructure of control within the next decade.

Urgent actions include:

- Strengthening export controls and supply chain oversight to prevent complicity.

- Enforcing privacy and speech safeguards in democratic legislation.

- Investing in technical countermeasures (circumvention, encryption resilience).

- Building international norms and treaties akin to arms control, but for digital repression technologies.

Key Takeaways

Authoritarian adoption and democratic creep are converging: Though starting from different justifications, both trajectories lead toward the same technical and political outcomes—routine surveillance and censorship.

The most acute near-term risk lies in Europe and Australia, where liberal democracies are actively legislating for mass surveillance under protective narratives.

By the long term (10 years), the distinction between “authoritarian” and “democratic” approaches may collapse. If current trajectories hold, most jurisdictions will operate with surveillance-by-default infrastructure.

Canada and the US are at risk of incremental entrenchment: while more contested politically, both are expanding surveillance powers in ways compatible with authoritarian systems.

The Data:

Rising Authoritarian Trends in Democratic Countries

Part 1: Overview and High-Level Analysis

Democratic societies are increasingly shifting from a “freedom first” posture toward a more authoritarian, security-driven stance. In recent years, governments in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and across Europe have adopted policies and rhetoric that prioritize state security and social “stability” over individual freedoms. This manifests in greater comfort with heavy surveillance, censorship of speech, and an erosion of privacy rights – trends traditionally associated with authoritarian regimes. Global data confirms this worrisome shift: 2024 marked the 19th consecutive year of decline in global freedom, with far more countries tightening political and civil liberties than loosening themfreedomhouse.orgfreedomhouse.org. Only 20% of the world’s people now live in fully “Free” countries, while 40% live under “Not Free” regimesfreedomhouse.org – a stark indication of freedom’s retreat even as authoritarian practices spread.

Notably, this “authoritarian creep” has not spared the First World. Many advanced democracies once seen as champions of free expression and privacy are experimenting with measures that curtail those very values. As one analysis warns, tools of digital repression pioneered by authoritarian states are now being “exported” and quietly adopted in democratic contextstechpolicy.press. The result is a slow normalization of surveillance and censorship: what once seemed unthinkable in a democracy – such as real-time monitoring of citizens’ communications or suppressing online speech – is gradually becoming thinkable, even routine. The messaging around freedom has evolved: leaders increasingly justify intrusive policies as necessary for national security, child protection, or countering misinformation. In short, the political zeitgeist in many democracies has tilted toward a protective (even paternalistic) stance, where violating certain individual freedoms is framed as an acceptable trade-off for collective security. Below, we provide an in-depth analysis of this trend in key regions, followed by supporting data and references.

Part 2: Detailed Breakdown of Trends and Regional Examples

United States – Security Over Liberty in Policy and Practice

In the United States, the balance between liberty and security has moved steadily in favor of the latter, particularly since the 2001 terrorist attacks. The USA PATRIOT Act and subsequent measures dramatically expanded government surveillance powers. Revelations in 2013 showed U.S. intelligence agencies conducting mass collection of phone and internet records worldwide, vacuuming up billions of communications with minimal oversightamnesty.org. While some of these programs have faced reforms, many persist. Key surveillance authorities are regularly renewed (for instance, Section 702 of FISA, which permits bulk interception of internet data), amid assertions that they are indispensable for national security. This has entrenched a “normal” baseline of surveillance that would have been extraordinary decades ago.

Crucially, U.S. political leaders and agencies continue to push the envelope on surveillance and control. A clear example is the repeated introduction of laws that ostensibly target crime or child abuse but carry broad authoritarian implications. The proposed EARN IT Act, for instance, was presented as an anti–child-exploitation measure – yet civil liberties experts note it “will strike at the heart of encrypted communications and undermine free expression on the internet.” It would pressure online platforms to scan and censor users’ private messages and could open backdoors in encryptionaclu.orgaclu.org. In effect, such policies ask companies to sacrifice user privacy and speech in the name of security. Similarly, officials have floated the “Kids Online Safety Act” and other bills that, while aimed at protecting children, contain dangerous provisions requiring age verification and content monitoring that imperil anonymity and free speech onlineeff.orgeff.org. The rhetoric around these efforts reveals the shift: lawmakers emphasize preventing harms and “bad actors,” even if it means eroding the longstanding American norms of robust free speech and privacy rights.

On the ground, surveillance has also expanded at state and local levels, often with public acquiescence. A vivid case emerged in New York City: a recent investigation found that the city’s “Big Apple Connect” free broadband program for public housing was quietly repurposed to feed live CCTV camera footage directly to the NYPD’s central surveillance system – all without informing residentsnysfocus.comnysfocus.com. This gave police unprecedented real-time access to monitor public-housing residents under the guise of providing internet access. The NYPD’s centralized platform (the Domain Awareness System) aggregates CCTV feeds, license plate reads, facial recognition, and other data for broad monitoring of citizensnysfocus.com. Critics, including civil rights groups, warn that such integrations create a constant monitoring regime where people in these communities are surveilled by default, chilling their freedom to assemble or protestnysfocus.com. Yet city officials defended the initiative as a crime-fighting tool. This example underscores how American authorities are increasingly willing to leverage technology to surveil domestic populations, and how programs touted as public benefits can double as surveillance infrastructure.

It’s important to note that public opinion in the U.S. is not uniformly behind this authoritarian tilt – polls indicate many Americans remain wary of government overreach (63% opposed their own government’s mass surveillance in one survey, versus only 20% in favor)amnesty.org. Nonetheless, the overall policy trajectory favors security: political support (at least among lawmakers and agencies) for broad surveillance powers remains strong. From the NSA’s continuing activities to local police use of face recognition and spyware, the U.S. exemplifies how a democracy can rationalize and sustain intrusive practices in the name of safety and order.

Canada – Eroding Privacy Traditions and Quiet Expansion of Surveillance

Canada, often perceived as a liberal democracy with strong privacy protections, has also shown signs of drifting toward security-first policies. As a member of the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance, Canada has long cooperated in global surveillance programs. Domestically, Canadian authorities have begun using powerful espionage tools against their own citizens – frequently without transparent legal frameworks or public knowledge. In 2022, Canada’s federal police (RCMP) admitted it had secretly employed on-device spyware (what they euphemistically call “On Device Investigative Tools”) for years to infiltrate suspects’ phonespolicyoptions.irpp.org. This spyware can remotely activate microphones and cameras and access all data on a device, essentially granting the government full surveillance within the most private sphere of life. The stunning fact was not just that these tools exist, but that the RCMP used them for years without explicit parliamentary authorization or oversight, exploiting outdated wiretap lawspolicyoptions.irpp.org. A parliamentary committee later found Canada’s legal safeguards lag decades behind – current law still assumes 1970s-era telephone taps and fails to set any clear limits on modern spyware deploymentpolicyoptions.irpp.orgpolicyoptions.irpp.org. In other words, Canadian law has not kept pace with technology, allowing law enforcement to push into invasive surveillance essentially by default.

Recent investigations reveal that this trend is accelerating. In 2025, researchers at Citizen Lab uncovered a “growing ecosystem of spyware” among Canadian police services, including evidence that the Ontario Provincial Police explored purchasing sophisticated spyware from an Israeli vendorpolicyoptions.irpp.orgpolicyoptions.irpp.org. The report so alarmed Ontario’s privacy commissioner that he issued a public rebuke, noting these police forces had never consulted his office about such a major privacy intrusion and calling the findings “significant concerns”policyoptions.irpp.org. Canada’s legacy as a defender of civil liberties is clearly under strain – as one analysis put it, “a legacy of privacy protection is eroding” in the face of new surveillance techpolicyoptions.irpp.org. This erosion is also evident in policy shifts: Canadian security agencies have taken a more assertive tone, echoing counterparts elsewhere. For example, officials emphasize the need to monitor extremists online and have pushed for laws that would ease access to data under the banner of national security. While Canada has not passed an equivalent to the Patriot Act, it has incrementally expanded surveillance powers (e.g. broad data-sharing under anti-terror laws and signals intelligence through CSE). The comfort with these moves marks a change in messaging – from a previous emphasis on privacy as a right (entrenched in Canada’s Charter and privacy laws) to a new acceptance that security concerns might justify encroachments.

It’s telling that Canadian authorities proceeded with invasive surveillance largely out of the public eye. Only through whistleblowers and reports did citizens learn that their communications might have been spied on via malware. This underscores how the shift toward authoritarian-style practices can happen quietly. Even without highly visible new laws, the effect is the same: individual freedoms shrink. Canadian civil society and privacy regulators are now scrambling to update oversight, but as of 2025 no robust new safeguards have been enactedpolicyoptions.irpp.org. In sum, Canada illustrates a slow but real slide away from the “privacy is paramount” philosophy, toward a stance where state security and policing objectives trump the expectation of personal privacy.

United Kingdom – Embracing Surveillance and Censorship for “Safety”

The United Kingdom has increasingly adopted an openly interventionist approach in the digital realm, justifying extensive surveillance and speech controls in the name of safety and security. The UK is already known as one of the most surveilled democracies (with ubiquitous CCTV cameras and broad intelligence capabilities), but recent moves go even further. In 2023, Parliament passed the Online Safety Act, a sweeping law that has been described by experts as “a deeply flawed censorship proposal”eff.org. Ostensibly meant to make the UK “the safest place to use the internet,” the law in fact grants authorities and the regulator (Ofcom) unprecedented oversight of online content and communications. Key provisions mandate platforms to monitor users’ content broadly, remove anything “harmful,” and even undermine encryption by installing government-approved scanning technology to inspect private messageseff.orgeff.org. If implemented fully, this would mean no truly private conversations for Britons online – a dramatic departure from the liberal principle that individuals have a right to converse without state eavesdropping. Privacy advocates point out the Act effectively creates a “blueprint for repression” that other governments could copyeff.org. It requires age verification for many sites (raising fears of surveillance and database leaks) and threatens harsh penalties (including jail) for vaguely defined offenses like causing “psychological harm” via a social media posteff.org. In short, the UK has signaled it is willing to sacrifice both privacy and free expression to police the internet.

This trend did not begin with the Online Safety Act. The UK has steadily expanded state powers through laws like the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (nicknamed the “Snoopers’ Charter”), which granted intelligence agencies and law enforcement broad authority to intercept communications and required telecom providers to store everyone’s browsing history for government access. At the time, such measures were hotly debated as potential violations of privacy. But over the past decade, the narrative from British authorities has consistently been that such surveillance is necessary to combat terrorism, child abuse, and other threats. That narrative gained political traction. Today, officials scarcely shy away from heavy-handed approaches. For example, the government has pressured messaging apps like WhatsApp to break their end-to-end encryption in order to comply with the new safety law – despite firm resistance from the tech industry on the grounds that this would compromise all users’ security. The home secretary and other ministers have explicitly argued that public safety should trump digital privacy when the two conflict, echoing the authoritarian line that stability and security justify intrusive controls.

Additionally, the UK has shown increasing willingness to restrict speech under broad umbrellas like “harmful content” or misinformation. Even before the new law, British authorities experimented with policing online speech – e.g. arresting individuals for offensive social media posts in some cases, and pushing for stronger moderation of extremist content. The cultural acceptance of speech limits in the UK (for instance, hate speech laws and libel laws far stricter than the US) has arguably paved the way for even greater controls. The Online Safety regime formalizes this by requiring proactive censorship: companies must remove not only illegal content but also content deemed “legal but harmful.” This creates a strong incentive to over-censor (to avoid penalties), potentially silencing controversial or minority viewpoints. It marks a significant shift from the ideal of the internet as an open forum. The bottom line is that Britain’s political establishment has largely embraced an approach that mirrors authoritarian logic – that expansive surveillance and content control by the state are justified to protect the public. Privacy and free speech advocates warn that the UK is trading away fundamental freedoms for a false sense of security, but for now the trajectory toward a surveillance state with extensive censorship powers is clearly advancingeff.orgeff.org.

Australia – Pioneering “Lawful” Intrusion and Normalizing Surveillance

Australia stands out as a case where a democratic government has explicitly prioritized surveillance powers, even at the expense of privacy rights, and has done so with relatively little domestic blowback. In fact, Australia was an early mover in this area: it passed a “world-first” anti-encryption law in 2018, the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (TOLA) Act, which compels tech companies to assist law enforcement in accessing encrypted communicationscsis.org. At the time, experts worldwide warned that this law was dangerously overreaching – essentially it empowers authorities to issue notices forcing companies to build new interception capabilities or backdoors if needed to read users’ messagescsis.orgcsis.org. Privacy advocates and tech firms lambasted TOLA as “dangerous” and harmful to digital securitycsis.org. However, Australia’s government defended it as a necessary tool against terrorism and crime, and indeed soon touted its use in major crime stings (like a 2021 operation where police covertly ran an encrypted chat service to ensnare criminal gangs)csis.org. Over time, the initial public resistance subsided, and the narrative shifted toward why even more might be needed – a telling development. By 2024, the head of Australia’s domestic intelligence agency (ASIO) publicly declared that “privacy is important but not absolute”, explicitly making the case that encrypted apps should not impede security operationscsis.org. This statement encapsulates Australia’s stance: individual privacy rights may be overridden whenever they conflict with security objectives.

Beyond encryption, Australia has continued to widen law enforcement powers. In 2021, it enacted the Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Act, which grants federal police sweeping authority to hack into networks, take over user accounts, and alter or delete data during investigationsbusiness-humanrights.org. These are extraordinary powers, unprecedented among peer democracies, effectively allowing authorities to impersonate users online or insert false evidence to “disrupt” criminal activity. The law passed despite serious privacy concerns from civil society – lawmakers ignored many recommended safeguards and gave agencies broad latitudebusiness-humanrights.org. The Human Rights Law Centre and digital rights groups in Australia warned that the law lacked checks and could be easily misusedbusiness-humanrights.org. Nevertheless, the political appetite for strong security tools prevailed over privacy arguments. This reflects a broader Australian political culture that has become increasingly amenable to surveillance and tough policing measures, perhaps influenced by the country’s generally high trust in government agencies and a desire to crack down on organized crime and extremist threats.

The result is that Australia now has one of the most expansive surveillance legal frameworks in the democratic world. From metadata retention mandates (ISPs must retain user metadata for two years, as per a 2015 law) to TOLA’s encryption backdoors to the 2021 hacking powers, the country has systematically fortified the state’s ability to monitor and control digital communications. And unlike in some other nations, Australian officials have faced relatively limited political backlash for these steps. Indeed, there’s a sense that each new power becomes normalized: what caused controversy a few years ago (like TOLA) is now taken for granted, such that agencies are comfortable complaining that even those powers are not enough. The ASIO chief’s commentary calling for more cooperation from tech companies – essentially asking for even greater surveillance capabilities – illustrates the slippery slopecsis.orgcsis.org. In summary, Australia’s experience shows how a democracy can pioneer authoritarian-style surveillance under color of law, and how public discourse can shift to accept “security over privacy” as a matter-of-fact principle.

Europe – Continental Drift Toward Surveillance and Speech Regulation

Across Europe, including the European Union and individual states, there is a discernible trend toward heavy regulation of online content and diminishing absolutism about privacy rights. The EU in particular has traditionally upheld privacy as a fundamental right (enshrined in the GDPR and human rights conventions). Yet even in Europe, leaders are increasingly willing to sacrifice some privacy and free expression in pursuit of security, public order, or other collective goals. A striking current example is the EU’s proposed Regulation to prevent and combat Child Sexual Abuse Material (dubbed “Chat Control”), which has alarmed privacy experts worldwide. This proposal, now gaining broad political support, would effectively require all messaging services – even end-to-end encrypted apps like WhatsApp, Signal, and iMessage – to scan every private message, photo, and file for prohibited content before encryptiondig.watch. In August 2025, it was reported that 19 out of 27 EU member states (a qualified majority) back this plan, meaning it is highly likely to become lawdig.watchdig.watch. If enacted, the law would institute mass surveillance of Europeans’ communications in real time. Not only would this obliterate the guarantee of confidential messaging, it also introduces mandatory age verification for internet users – potentially stripping anonymity from many online platformsdig.watch. Critics have described the scheme as Orwellian, arguing it “amounts to real-time surveillance of private conversations and threatens fundamental freedoms.”dig.watch The justification offered by proponents is the protection of children – a goal few oppose – but the methods represent a dramatic policy departure for liberal democracies. Even some companies and technologists warn they may be forced to withdraw services from Europe rather than compromise encryption. Nonetheless, the momentum behind the law suggests European governments are comfortable with intrusive measures that would have been politically unthinkable a decade ago.

Europe’s tilt isn’t only about privacy versus surveillance – it’s also evident in the arena of speech and information control. Many European democracies have long had laws against hate speech or Holocaust denial, which set them apart from the U.S.’s broad free speech protections. Now, new challenges like disinformation and online extremism have led to a flurry of regulations that expand state influence over online content. The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which took effect in 2023, puts stringent obligations on platforms to remove illegal content quickly and to assess and mitigate “systemic risks” such as disinformation. While the DSA includes transparency and due-process provisions, it cements a norm that governments can and should dictate content moderation standards. Individual countries have gone even further at times: Germany’s NetzDG law (in force since 2018) requires social media firms to delete obvious illegal content (hate speech, threats, etc.) within 24 hours or face heavy fines. France has aggressively policed extremist content and even pressured platforms directly to censor content – Telegram’s founder Pavel Durov recently revealed that French officials demanded the platform censor certain political content, a request he refused, warning that Europe’s mounting regulatory pressure could lead to “censorship” and even societal declinedig.watch. These examples show that European authorities, even in liberal democracies like France, Germany, or Spain, are increasingly willing to intrude on online expression under the banners of security, countering hate, or public health (as seen during COVID-19 misinformation crackdowns).

The political climate in Europe has thus shifted toward a protective, state-guided model for the internet, sometimes called “digital sovereignty.” Citizens are still broadly supportive of human rights, but many also express concerns about security, terrorism, and cohesion, which leaders have been keen to address by empowering the state. Ironically, Europe continues to champion external data privacy (for example, challenging tech companies on data handling), yet is internally contemplating surveillance measures (like Chat Control) that rival those of autocratic regimes. This duality is noted by Freedom House, which observed that even laws billed as protecting users often contain broad national security exceptions that allow surveillance and data accessfreedomhouse.org. Indeed, “national security” has become a catch-all rationale in Europe to justify everything from data localization mandates (keeping data accessible to local authorities) to proposals for weakening encryptionfreedomhouse.org. The overarching trend is clear: first-world democracies in Europe are incrementally moving away from treating privacy and unrestricted free speech as inviolable rights, and toward an approach that grants the state greater control over the digital sphere. This is statistically reflected in global freedom indexes (several European countries have seen small declines in scores) and in the proliferation of new laws enabling censorship or surveillance. If this trajectory continues, analysts warn that the line between open democracies and overt digital authoritarianism will continue to blurtechpolicy.press, undercutting the very values that liberal democracies were thought to stand for.

Part 3: Verified References (with Direct Links)

Tech Policy Press – “The Internet Coup Is Here. And the World Is Still Asleep” (Sept. 23, 2025). Perspective piece by Konstantinos Komaitis describing how authoritarian internet control tools (censorship, surveillance) are spreading globally and even democracies are quietly adopting them. Emphasizes the normalization of once-unthinkable digital repression in democratic countries. URL: https://techpolicy.press/the-internet-coup-is-here-and-the-world-is-still-asleep

Freedom House – Freedom in the World 2025 Press Release (Feb. 26, 2025). Reports that 2024 marked the 19th consecutive year of global freedom decline. Provides data on the number of countries deteriorating in political rights/civil liberties versus improving. Notably states only 20% of the world’s population now lives in “Free” countries, highlighting the worldwide shift away from liberal democratic norms. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/article/new-report-amid-unprecedented-wave-elections-political-violence-and-armed-conflict-fueled

New York Focus – “Adams Quietly Uses Free Internet at NYCHA to Expand Police Surveillance” (Aug. 11, 2025). Investigative report revealing that New York City’s free broadband program for public housing (NYCHA) was used to link CCTV cameras directly into the NYPD’s Domain Awareness System. Confirms that residents were not informed and that police gained real-time remote surveillance of public housing communities. Illustrates how a democratic city expanded surveillance under a public safety rationale. URL: https://nysfocus.com/2025/08/11/eric-adams-nycha-nypd-cameras-surveillance

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) – Analysis of the UK Online Safety Act/Bill (2022–2023). EFF’s critique of the UK’s Online Safety Bill (now Act) explaining its threats to privacy and free expression. Details how the law mandates broad content monitoring, undermines end-to-end encryption (by requiring scanning of messages), and creates a “blueprint for repression” according to civil society groups. This source highlights the UK’s shift toward state control over online speech and data. URL: https://www.eff.org/pages/uk-online-safety-bill-massive-threat-online-privacy-security-and-speech

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre – “Australia: Surveillance law passed, giving sweeping powers to intelligence agencies despite privacy concerns” (Aug. 25, 2021). Summarizes Australia’s Identify and Disrupt Act 2021 and reactions to it. Confirms that the law grants unprecedented powers to Australian Federal Police and intelligence (account takeovers, data disruption) and notes that many recommended safeguards were ignored. Civil society warnings about privacy dangers are cited, showing Australia’s willingness to expand state power at the expense of rights. URL: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/australia-surveillance-law-passed-giving-sweeping-powers-to-intelligence-agencies-despite-privacy-concerns/

Policy Options (Institute for Research on Public Policy) – “Canada’s outdated laws leave spyware oversight dangerously weak” (July 2, 2025). Analysis by legal researchers on the use of “mercenary spyware” by Canadian police. Describes the 2022 admission by the RCMP of using spyware tools for years, and a 2025 Citizen Lab report linking Canadian police to spyware purchases. Explains that Canada’s legal framework (wiretap laws) hasn’t kept up, lacking safeguards for modern surveillance tech – leading to an erosion of privacy protections. URL: https://policyoptions.irpp.org/2025/07/mercenary-spyware/

Digital Watch Observatory – “EU proposal to scan private messages gains support” (Aug. 6, 2025). News update on the European Union’s draft law to combat child abuse material by scanning all encrypted messages (nicknamed “Chat Control”). Confirms that 19 EU member states support scanning messages before encryption (client-side scanning), and discusses privacy concerns and the inclusion of mandatory age verification. This source provides evidence of Europe’s trend toward mass surveillance in the digital domain. URL: https://dig.watch/updates/eu-proposal-to-scan-private-messages-gains-support

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) – “The EARN IT Act is a Disaster for Online Speech and Privacy” (June 30, 2020). Explains the U.S. EARN IT Act and its implications. Although dated 2020, it remains relevant as the act has been reintroduced in subsequent Congress sessions. The article details how EARN IT would pressure platforms to broadly monitor and censor user content and could undermine encryption by allowing law enforcement “backdoor” access – exemplifying U.S. legislative attempts that prioritize law enforcement goals over privacy/free speech, under the pretext of child safety. URL: https://www.aclu.org/news/free-speech/the-earn-it-act-is-a-disaster-for-online-speech-and-privacy-especially-for-the-lgbtq-and-sex-worker-communities

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) – “Revisiting Australia’s Encryption Landscape” (Aug. 20, 2024). A blog post reviewing Australia’s anti-encryption law (TOLA 2018) and current debates. Notably quotes the head of ASIO saying “privacy is important but not absolute,” reflecting the official mindset. Describes how TOLA works (industry notices to facilitate decryption) and its use in law enforcement operations, as well as the diminishing public controversy over these powers. This underscores the normalization of surveillance powers in an advanced democracy. URL: https://www.csis.org/blogs/strategic-technologies-blog/revisiting-australias-encryption-landscape

Freedom House – Freedom on the Net 2021 Report (Sept. 2021), Global Findings. Provides context on how governments worldwide – including some democracies – passed new laws to control online content and access data. Notes that many governments enacted rules undermining encryption or mandating data localization (forcing user data to be kept in-country for easier access), often justified by national security. This illustrates the broader pattern of increasing state surveillance powers at the expense of user rights online. URL: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2021/global-drive-control-big-tech

Risk Assessment:

Summary of the Article’s Claims

Core Assertions

- A structural shift in global internet governance is underway: censorship and surveillance infrastructure is being normalized and exported, amounting to a slow “coup” against the open internet.

- China plays a leading role by exporting turnkey censorship and monitoring systems (e.g., Geedge Networks) to authoritarian governments.

- These systems include deep packet inspection, VPN blocking, throttling, targeted filtering, and real-time user monitoring, enabling states to control digital spaces at scale.

- Western firms are implicated through supply chains, components, or software licenses that underpin these systems.

- Democracies themselves are drifting toward similar tools, not through overt authoritarianism but through legislation and policies framed as necessary for security, child protection, counter-terrorism, or combating disinformation.

- Once embedded in critical infrastructure and normalized politically, these controls become difficult to reverse.

- There is urgent need for coordinated responses: international regulation, stronger export controls, civil society oversight, and development of technical countermeasures.

What the Evidence Strongly Supports

- Document leaks confirm China’s export of censorship technology: The InterSecLab report on Geedge Networks provides detailed internal evidence of sales to states such as Kazakhstan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

- Capabilities are verified: tools include DPI, VPN disruption, throttling, selective filtering, and surveillance features.

- Supply chain complicity exists: Western/EU technology has been traced into these censorship systems, raising compliance and governance risks.

- Democratic parallels are emerging: Evidence from the US, Canada, UK, Australia, and EU shows an incremental but clear trend toward adoption of censorship-enabling legislation (e.g., UK Online Safety Act, EU “Chat Control” proposal, Australia’s encryption backdoors, Canada’s spyware use, US EARN IT proposals). These provide early confirmation of the “creep” the article warns about.

What Remains Uncertain or Speculative

- Scale of adoption: The technology is deployed in a handful of authoritarian states, but it is not yet global or ubiquitous.

- Durability of entrenchment: While difficult to reverse once installed, there are still legal, civil, and technical countermeasures that can slow or dismantle these systems.

- Democratic willingness to fully embrace authoritarian models: While the trend lines are visible, mature democracies have not yet converged on full authoritarian control; current measures are piecemeal and often contested.

- Strategic intent attribution: It is unclear if China’s export is a deliberate geopolitical strategy to reshape norms or simply opportunistic commercial activity.

- Rhetorical framing: The metaphor of an “internet coup” is more rhetorical than empirical; the shift is real but uneven and slower than implied.

Refined Risk Trajectory

- Current (2025): Moderate risk, with authoritarian exports documented and democracies experimenting with surveillance-enabling laws.

- Mid-term (3–5 years): High risk as more states adopt such systems, and democratic governments normalize surveillance and speech restrictions under protective narratives.

- Long-term (10 years): Very high risk of entrenched global fragmentation (“splinternet”), where authoritarian models become normative, even in parts of the democratic world.

Key Implication

The true inflection point is not only the export of censorship tools to authoritarian states, but the parallel erosion of liberal democratic norms. Democracies, under the guise of security, are increasingly adopting infrastructure and laws compatible with authoritarian control. The convergence of these trends suggests a serious structural threat to the open internet if not checked by policy, technical safeguards, and international pressure.