Who is in control – the debate over article 9 for the EU digital wallet

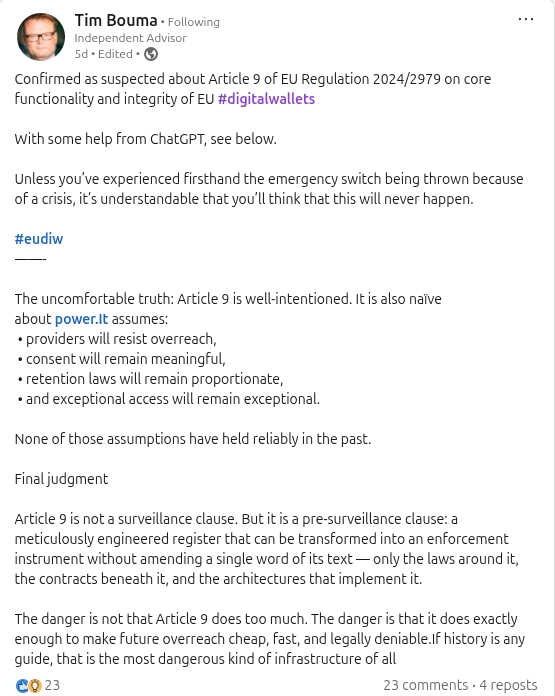

Tim Bouma posted the following on linkedin:

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/trbouma_digitalwallets-eudiw-activity-7412618695367311360-HiSp

The thread kicked off with Tim Bouma doing what good provocateurs do: he didn’t argue that Article 9 is surveillance, he argued it is “pre-surveillance” infrastructure. His point wasn’t about intent. It was about power—providers don’t reliably resist overreach, consent degrades, retention expands, and “exceptional access” becomes normal. The claim is simple: build a meticulous transaction register now, and future governments won’t need to amend the text to weaponize it; they’ll just change the surrounding law, contracts, and implementation defaults.

Other posters pushed back hard and stayed on the privacy as advertised position. Article 9, was argued, mandates logging for accountability and dispute resolution, not monitoring. Access and use are only with user consent. Without a transaction history, the user can’t prove that a relying party asked for too much, or that a wallet provider failed them—so “privacy” becomes a marketing chimera because the user is forced to trust the provider’s story. In other words: the log is the user’s evidence mechanism, not the state’s surveillance feed.

That’s where the conversation split into two different definitions of privacy. One side treated privacy as governance: consent gates, regulated actors, and legal process. The other (in my responses ) treated privacy as architecture: if the system can produce a readable activity trail outside the user’s exclusive key control, then “consent” is a policy dial that can be turned, bundled, pressured, or redefined—especially once you add backups, multi-device sync, support workflows, and retention “as required by law.” Tim then distilled it to a meme (“You’re sheltering logs from the state, aren’t you?”)

, and the response escalated the framing: regulated environments can’t be “pure self-sovereign,” and critics who resist logging end up binding users to providers by removing their ability to evidence what happened.

That is the real disagreement: not whether accountability matters, but whether accountability can be delivered without turning transaction metadata into an asset that naturally wants to be centralized, retained, and compelled. And that is exactly why the safe analogy matters.

Article 9 is a perfect example of old ideas of accountability and tracking of transactions failing to understand what privacy is. If data is not E2EE and the owner of the data does not have full and exclusive control of the key, it is not private – period.

This is best illustrated by looking at the digital wallet as a safe. If you buy a safe you expect it to be a solid and trustworthy mechanism to protect your private and precious items. Things that go in the safe do not lose their characteristics or trustworthiness because they are in the safe, and their value travels with the item. The safe provides the individual with control “holding the keys” the confidence (trusting the safe builder did a good job and didn’t sneak in any “back doors” for access or a hidden camera transmitting all the items and action from the safe to themselves or a third party. If any of these things were present it would make the safe completely untrustworthy. For a digital wallet, the analogy holds up very well and the parallels are accurate.

This concern is really a question about what you trust. The default assumption behind an “outside verifiable record” is that an external party (a provider, a state system, a central log store) is inherently more trustworthy than an individual or a purpose-built trust infrastructure. That is a fallacy. The most trustworthy “record” is not a third party holding your data; it is an infrastructure designed so that nobody can quietly rewrite history—not the user, not the provider, not the relying party—while still keeping the content private.

Modern systems can do this without leaking logs in the clear:

- Tamper-evident local ledger (append-only): The wallet writes each event as an append-only entry and links entries with cryptographic hashes (a “hash chain”). If any past entry is altered, the chain breaks. The wallet can also bind entries to a secure hardware root (secure enclave/TPM) so the device can attest “this ledger hasn’t been tampered with.” The evidence is strong without requiring a provider-readable copy.

- Signed receipts from the relying party: Each transaction can produce a receipt that the relying party signs (or both parties sign). The user stores that receipt locally. In a dispute, the user presents the signed receipt: it proves what the relying party requested and what was presented, without requiring a central authority to have been watching. The relying party cannot plausibly deny its own signature.

- Selective disclosure and zero-knowledge proofs: Instead of exporting a full log, the wallet can reveal only what is needed: e.g., “On date X, relying party Y requested attributes A and B,” plus a proof that this claim corresponds to a valid ledger entry. Zero-knowledge techniques can prove integrity (“this entry exists and is unmodified”) without exposing unrelated entries or a full activity timeline.

- Public timestamping without content leakage: If you want third-party verifiability without third-party readability, the wallet can periodically publish a tiny commitment (a hash) to a public timestamping service or transparency log. That commitment reveals nothing about the transactions, but it proves that “a ledger in this state existed at time T.” Later, the user can show that a specific entry was part of that committed state, again without uploading the full ledger.

Put together, this produces the property Article 9 is aiming for—users can evidence what happened—without creating a centralized, provider-accessible dossier. Trust comes from cryptography, secure attestation, and counterparty signatures, not from handing a readable transaction record to an outside custodian. The user retains exclusive control of decryption keys and decides what to disclose, while verifiers still get high-assurance proof that the disclosed record is authentic, complete for the scope claimed, and untampered.

The crux of the matter is control, and Tim Bouma’s “Things in Control” framing is the cleanest way to see it: digital objects become legally meaningful not because of their content or because a registry watches them, but because the system enforces exclusive control—the ability to use, exclude, and transfer (see Tim Bouma's Newsletter). That is exactly why the safe analogy matters. The debate is not “should a wallet be trusted,” it’s “who owns and can open the safe—and who gets to observe and retain a record of every time it is opened.” The instinct behind Article 9-style thinking is to post a guard at the door: to treat observation and third-party custody of logs as the source of truth, rather than trusting the built architecture to be trustworthy by design (tamper-evident records, receipts, verifiable proofs, and user-held keys). That instinct embeds a prior assumption that the architecture is untrustworthy and only an external custodian can be trusted; in the best case it is fear-driven and rooted in misunderstanding what modern cryptography can guarantee, and in the worst case it is deliberate—an attempt to normalize overreach and shift the power relationship by reducing individual autonomy while still calling the result “personal” and “user-controlled.”