The Gift

Let Usal tell you of his home world

Reading now in the 21st century is a markedly different affair than it was at the beginning of the 20th. No doubt it is the speeding up of the world that has demanded our attention no longer be allowed to drift and linger with the written word. Books and articles written today seem less able to truly engage and exercise the brain. It is not as if reading now is no exercise at all… but it is more like a stroll versus a vigorous run. While I do enjoy many books written in the last quarter of a century, to truly revel in a novel and wordsmithing, one would do well to reach further back in time to what we now consider the classics. Those men and women will truly require engagement.

I have been reading Hemmingway's A Farewell to Arms for the first time. So far, it is an exploration of life serving as an expat in the Italian army during WW1. His writing is so terse, but not rudely so like Burkowski or Salinger. It is simply absent of flowery accoutrement which allows for an interesting ability to not only be engaged and entertained but also experience some realtime analysis as you read.

The spartan beauty with which Hemmingway approaches his protagonists experiences is a delight. It is not just leaving out details, like stripping a car to the chassis and driving it around. It is more as if he has designed a vehicle with only the necessary accessories and not one single thing more than what is needed to be a form of transport. In chapter 9, the protagonist, Frederic Henry, is in a mortar attack and wounded. The author’s approach to the very human details of the moments before, during and after the attack triggered something for me regarding my father, my family and my entire approach to life.

I strive in life for a goal of utilitarian purpose. That is to say, I hope at the end of all things to have been a very good bookend. If I can manage to be an interesting bookend, then I will have exceeded my expectations. In the 21st century, this seems to be a common theme with my generation in the west. Steady forward momentum with the expectation of failure or abandonment at any given moment. Which I can only attribute to the way our parents loved us (or did not in many cases). As the materialism of the baby boom generation shifted into third gear, things replaced physical touch, time and quality conversations. I love you and hugs were displaced with new hi-fi stereo systems, second and third televisions in the home and eventually video games. The introduction of cable tv meant you didn’t have to watch a program and turn off the set, you could now just be mesmerized waking moment to faltering sleep. People worked harder and were entertained more than ever. So the concept of family was commodified and used to sell us dish soap and cereal instead of providing safe, consistent experiences that would make us emotionally steady and ready for the world.

That is not to say our (my) parents did not love me. An important point to understand is that my father and I have always been friends. Not the kind who watch and go to games together, or have long contemplative conversations over a beer and a fishing rod about life, the universe and everything. But the kind where mutual respect and love is understood and expressed through subtle secondary actions. He grew up without a father and so, I assume, never learned how to be the warm-affectionate-type of dad. He taught me a good work ethic, mechanics, carpentry, and how to make things. I held lights and handed him tools instead of playing ball. But hugs and I-love-yous were not part of the curriculum. I describe him as an emotionally absent dad. Not in a cruel way, I believe this approach to life is likely fairly typical of western men in the 20th and 21st centuries (also probably the 1st through the 19th).

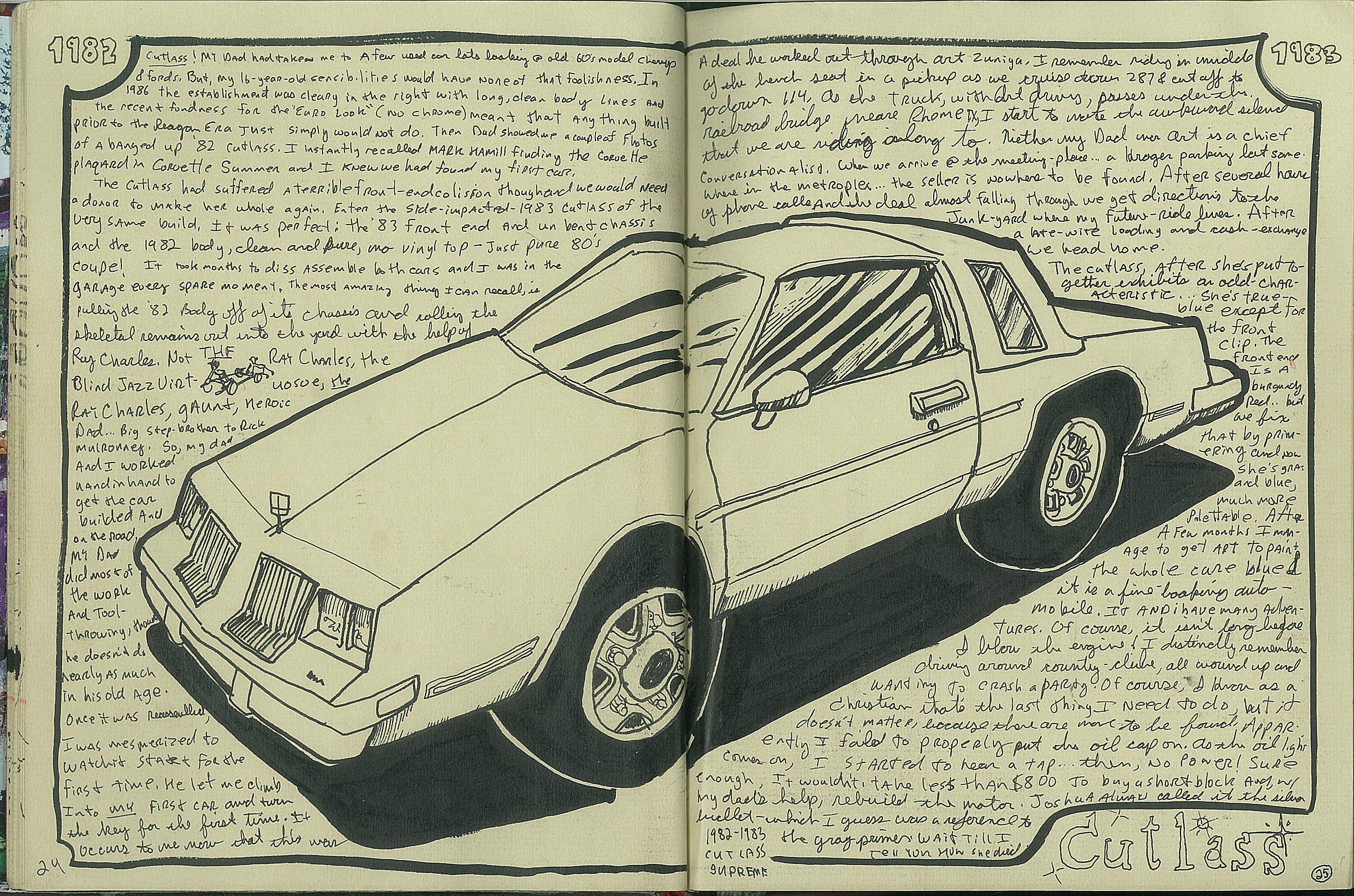

My mother shared with me recently the event of my birth whereupon my father, full of joy and passion told her, ‘I’m going to teach him everything I know. I’m going to teach him to draw and to build things and how to work on cars. I’m going to buy him a classic (car) and we’ll rebuild it together.’

This is probably the most touching thing I’ve ever heard about my father.

And he was prophetic. As soon as I was old enough to follow him around, that’s what I did. Remodeling their first house, he would draw little characters on all of the walls before finishing the sheetrock and I would poorly imitate his masterful drafting right along side. There is a mental tattoo of the heroic lion’s head he drew on my plaster cast when I broke my leg in second grade. That cast-drawing made my leg the coolest thing in class for a long time. He had this little tool shed when I was very young into which he would climb and put nails in the wall for each of his tools and then draw an outline around each one so he knew where they went. I can still smell the chemical marker and see the empty outlines left as tools were used and sometimes lost. Over the course of 10 years, he would build progressively bigger tool sheds until I was 15 he had constructed large shop and we were working together rebuilding my first car, a 1983 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme. I failed him on the classic car, much to my regret now. But I loved that Olds and like most people wish I still that first car.

To the point of my realization: I have known my whole life that he was in Viet Nam. He NEVER talks about it other than a rare reflection of some small moment he recalls. I have long been interested in his time there and what it was like. But the few stories I ever got were related to his mechanical prowess as he worked in the artillery division and was tasked with moving, unsticking and setting up the big ‘6-guns’. He has shared some pretty clever solutions for things like how to keep the giant trailer weapons from digging themselves into big holes as they fired shell after shell at the enemy.

> A lot of my understanding of the world comes from vehicle maintenance

Just before the attack in A Farewell To Arms, Frederic (the book’s protagonist) is in the colonel’s bunker discussing soup and the need to make sure his fellow ambulance drivers are fed. In the middle of the conversation the colonel, who is the mastermind initiating the attack, states without fanfare, ‘the attack is starting’. Hemmingway describes the booming of distant cannons firing at enemy locations. It is very nonchalant and does not interrupt their discussion regarding the soup in the least. That such mundane topics such as lunch would impose on a matter that would cost many men’s lives and untold suffering struck in me in a particularly visceral way. Frederic collects the meal and dashes across the compound to the bunker where he and his compadres are weathering the return fire. As the team of drivers discuss the soup and lack of utensils with which to eat, a shell strikes. A ‘trench mortar’ tears into the shelter, killing and injuring the team. The sequence shocked me at how it went from mundane to life-altering in the same moment.

Lo and behold, I'm reading about the attack and all of a sudden, at 51, I realize that my father is a victim of PTSD! I know, you will say this is an obvious expectation from someone who fought in that southeastern Asian nation. For whatever reason, this fact has only ever occurred to me in this moment. Like a blind man suddenly gaining sight. We as a family or father and son have NEVER discussed this. It is as if it never occurred to anyone to mention that to me or my sisters. I suppose, it is one of those matters the family was ignorant of in their youth and later assumed adults would realize matters for themselves. All of a sudden, I am reframing the anger and tension in our household as a child. The lost tempers and shouting. Why both of my sisters sought out abusive men in their relationships time after time and why I fight those behavioral demons in my own thoughts and actions.

It is a masterpiece of revelation. As I write this it is so new to me that I am not even sure what to do with the knowledge, if anything (I have since gone on to relate this experience to many friends). But for a certain, I can finally comprehend a lot of my childhood. One concept of my parents is responsible and loving and another concept is not. This informs my thinking on why I have the potential (and sometimes practice) of being such a jerk.

I will sit sometimes, and I've written about this a lot, I will sit and have this self-awareness that I am somehow two people. A good man and a bad man and sometimes, most of the time, the good guy is running the show. But once in a while, he will step out and Mr Hyde takes the wheel. This conflict is super-weird, I have even wondered if it is some mental illness trying to take root. But, my new thinking is this is behavioral garbage from when I was young that climbs up out of the depths of my psyche. And this is not just my baggage, but my father’s and mother’s as well as their father’s and mother’s.

My paternal grandfather was a veteran of WW2, but died in 1956 from stomach cancer. This left my own father without that critical male role model at the tender age of 9. I do not know this, but if I had to guess, I would say that grandpa was likely fighting his own post-conflict shadows, as most do.

Adding insult to even more injury, my maternal grandfather was a veteran of WW2 as well as the Korean conflict and a life-long alcoholic. While I did not experience it, my sisters reported that toward the end of his life, he mellowed and sobered and was a pretty decent fellow. Ah, the power of the character arc! Of course, I understand now that he was hiding from his own silent specters in the form of PTSD. My mother carried this weight with her through her entire life and likely still does.

This stuff is like the gift that keeps on giving. Recognizing it though... it's fascinating and will maybe make it easier to cope with my personality flaws, but there is no solve. Yet another matter that only God's kingdom can truly repair.

Just wait until I tell you about my (not-hyperbolically) brain-damaged sister.

Come, Lord Jesus.

WolfCast Home Page – Listen, follow, subscribe

Thank you for coming here and walking through the garden of my mind. No day is as brilliant in its moment as it is gilded in memory. Embrace your experience and relish gorgeous recollection.

Into every life a little light will shine. Thank you for being my luminance in whatever capacity you may. Shine on, you brilliant souls!

— Go back home and read MORE by Wolf Inwool

— Visit the archive

I welcome feedback at my inbox