Sleeping in Socks (rec)

I could care less about sleeping in anything else, but never socks. Never.

For the record, Wolf hates sleeping in socks.

Given the choice, I prefer sleeping as I was created: nothing between me and my dreams but a downy cover. If it’s warm, you can keep the blanket.

But my feet? They must always be naked.

I am so weird about my feet.

My third Friday in Europe turned out to be way more of a party than I anticipated. A day that started late, grew organically, and delivered some of the highest highs, along with a bit of a sour note at the climax.

Busy days and late nights mean slow starts in the morning. The day saw me rousing between 8 and 9 a.m. CET. As the apartment is on the first floor and settled between rows of tall buildings, it is never clear to me early in the morning if the sun is shining or not.

Stepping out into the frosty morning in my flannel pajamas, I glimpse blue sky and deduce that today will be a brilliant day to be out running around. So I do the next logical thing:

I sit inside and write for four hours.

When the wife finally stirred, we planned a visit to the Sofía Reina to see art—specifically Picasso’s Guernica. There is some debate as to the best way to transfer: bus, train, or Uber. Bus is the most convenient for short hops, and so we shower, dress, and dash out the door.

Naturally, we can’t just get on the bus. First, we have to find an orange.

In the neighborhoods of Madrid, there are fruit stands on every block. Sometimes two. Oranges are in season right now, so you look for the orbs with leaves attached. It’s an indication that they are the freshest. Twenty cents for a plump, luscious bite of citrus.

Then, of course, we needed a café, where I stumbled through my very limited Spanish to order a coffee and empanada. I failed to correctly distinguish between meat (carne) and chicken (pollo). But it was very good in spite of the mis-order.

Strolling and window-shopping is a delight on a brisk, sunny Friday morning, and so we leisurely gawk at stunning evening gowns, fancy luggage, and sundries of all kinds.

I’ve just eaten, but I find the smell of fried chicken irresistible. Stopping at an open window, I ask for “un pollo, por favor.” It takes a moment, as the cook fries it only when you ask, and it is deliciously hot and fresh—a plump, juicy breast so hot it steams in the morning cold.

Thank you, missus chicken. You were delicious.

I finish just in time for the number 39 to roll up and swipe my metro card twice. Beep, beep. A total of three euros for us both to ride across town to the Sofía Reina.

I have discovered I really enjoy riding the buses here. They are clean, well-lit, and cared for. People-watching is a lot of fun, though drawing while riding is kind of a challenge, as we’re rarely on the bus very long. And there’s plenty to see through the windows.

Hopping off at the Atocha stop, we cross a VERY busy intersection. This is close to the city center and the busiest spot I’ve yet walked. I think I could spend all day here watching the mortar going about their lives.

The Museo Sofía Reina is in the middle of a 20-year upgrade/restoration. The exterior is in varying states of shrouded construction tarps and fancy louvered metal veneer. The veneer is interesting, but it is most certainly one of those design styles that will age poorly and forever date the upgrade.

After tickets and an audioguide, we start the sojourn into this MASSIVE institution. It might be the biggest museum I’ve ever been in. It is a repurposed government building, and so it isn’t ideal. The structure is a large rectangle whose middle is a courtyard/garden. From above it looks like a giant, squared-off letter “O.”

The galleries are all old office spaces on the outer wall. This is awkward because it creates a labyrinth: some galleries huge, some tiny, some dead ends. And the official map is pretty useless.

So getting lost becomes a ritual. We ask “¿Dónde estamos nosotros?” (Where are we?) of the museum attendants. They can almost always show us on the map where we are, but it isn’t super useful information since nothing else is clearly labeled.

But the art is worth it.

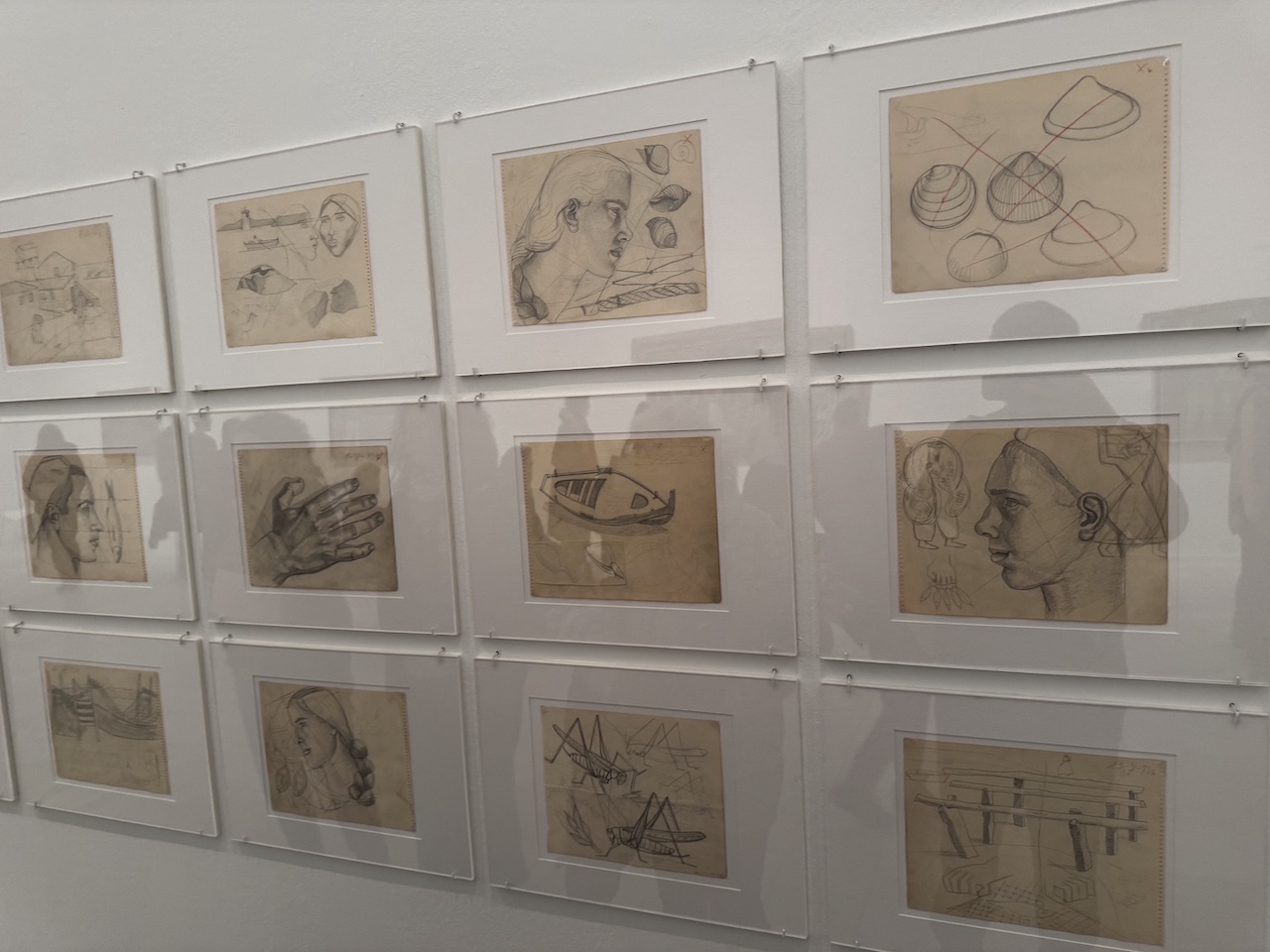

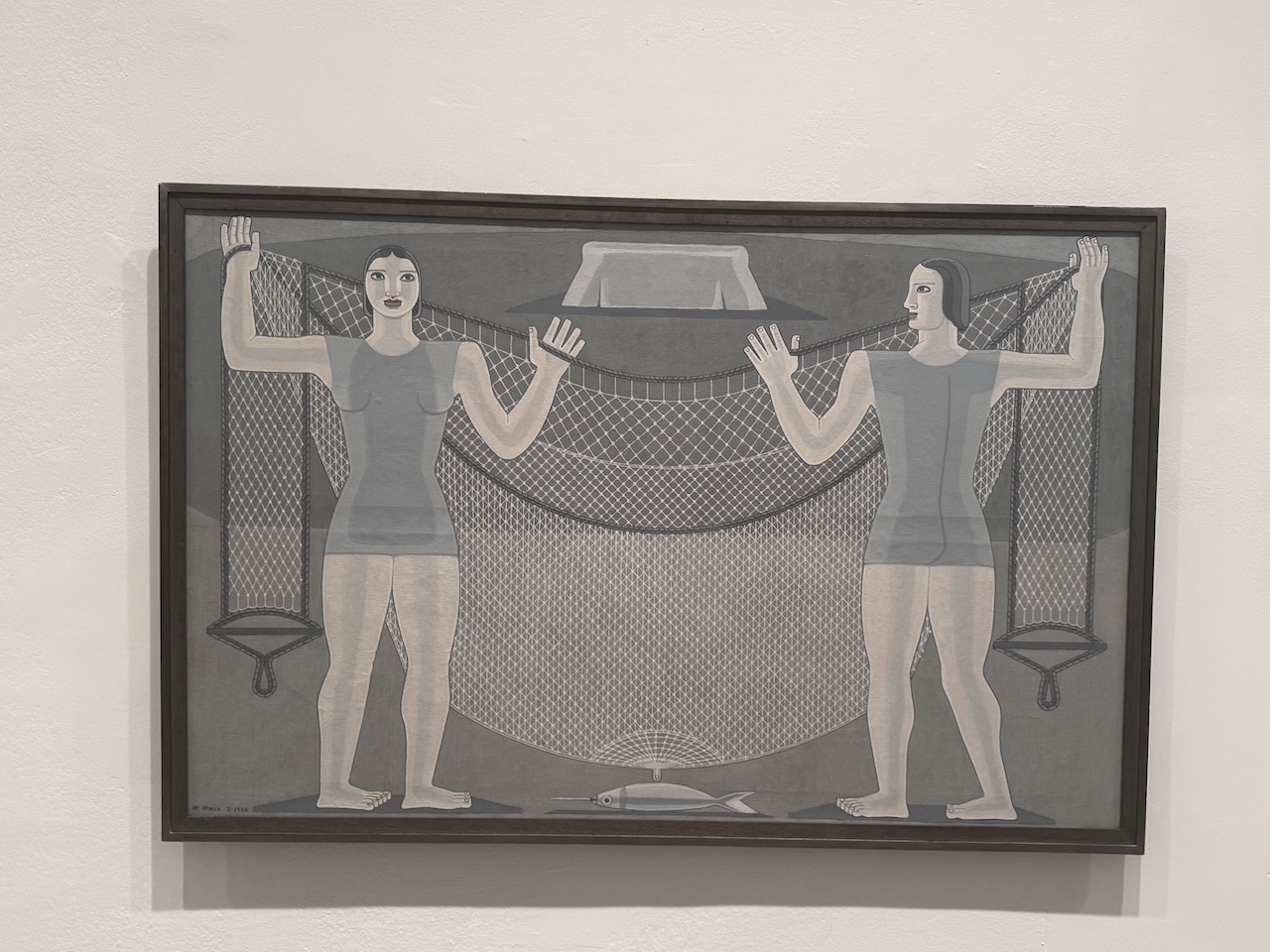

The first floor hosts traveling exhibits, and we are able to see work by little-known Spanish artists. Very intriguing shapes and colors, and carnival scenes that seem universal to every human.

One gallery has massive—I mean MASSIVE—monolithic steel slabs. The literature says they weigh thirty-eight tons.

The placard explains that they were lost for twenty years, stored in a warehouse that was sold and sold and sold until no one knew where the humongous slabs went.

My assessment: sold for weight.

So in 2002, the artist recreated the monoliths and made the Sofía Reina docents very happy—and no doubt lined the artist’s pockets handsomely. Good for you, artist. Grab that money for the rest of us.

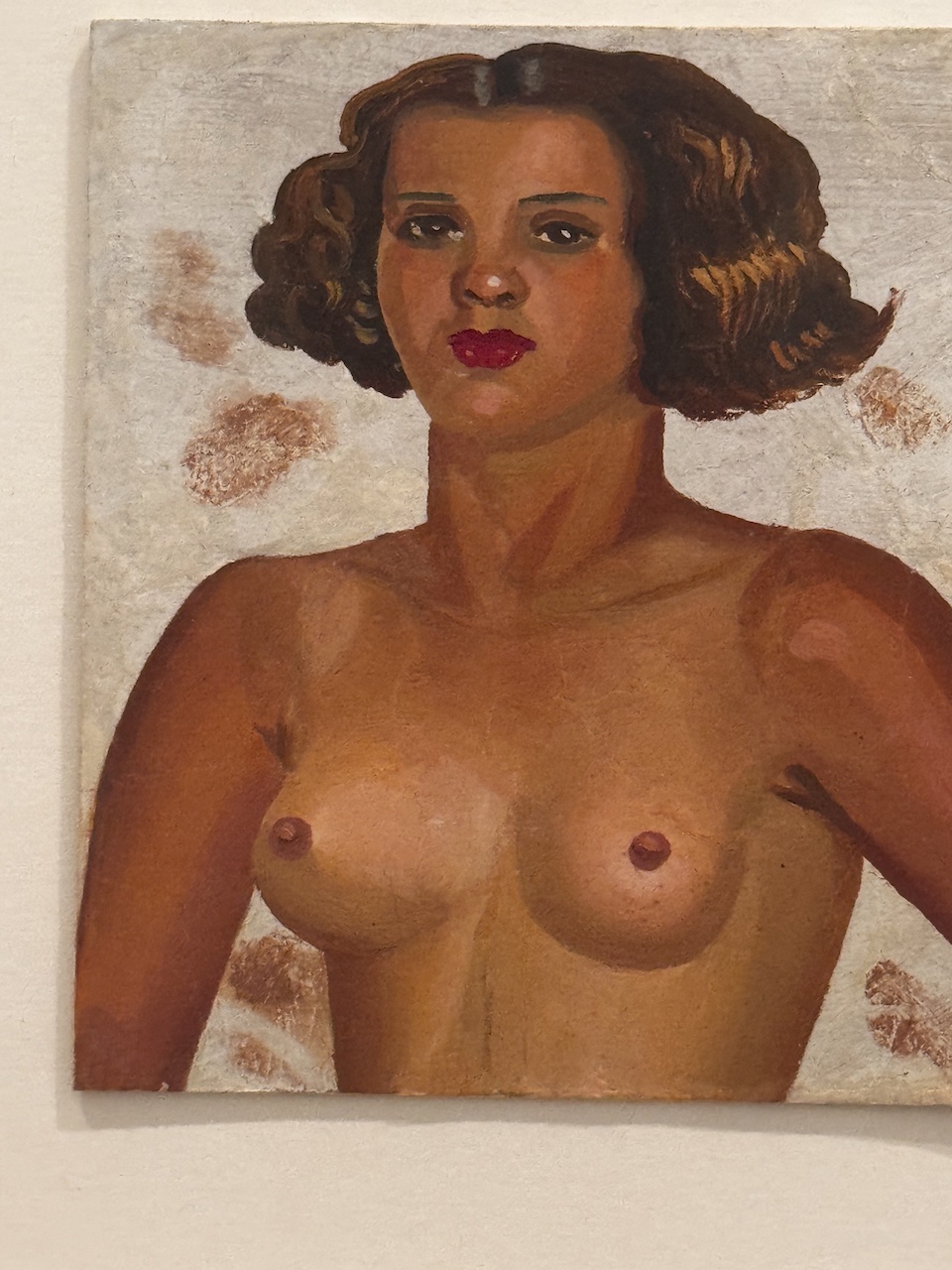

There is an exhibition by a very old artist who has spent her lifetime painting crisp works in gouache and acrylics. Her most striking pieces depict people—mostly women—with agricultural themes. I am inspired by her portraits and larger works that carry aquatic and agrarian motifs.

As with most moving art, I question why I don’t paint more—especially portraits. The people who mean the most to me should get painted. I am also in love with her nudes. I love painting nudes and believe everyone should experience the power of either being the artist or the subject. Both, if possible. I have yet to be the subject for someone, but I think I might be ready.

For a certainty, I long to paint some more than others.

My first real thrill, though, comes from Picasso’s Woman in Blue. His figurative work always surprises me because his cubist work is so heavily promoted. But Woman in Blue is quite lovely and striking. She’s heavily gowned in a massive, rich dress and completely covered except for her face, which is painted as heavily powdered with red cheeks. Her expression is forlorn, eyes distant—somewhat sad.

The placard explains that she is a prostitute, and that Picasso loved portraying the marginalized people he found in life.

I am reminded of my own recent realization and fascination with what I termed the “mortar” of life—those people and places largely overlooked by society, yet absolutely part of the fabric. We love the lightbulb, but need the miles of wire to make what it is.

The hour is late, and as the museum opens its doors for free during the last two hours of the night, I worry about the crush of incoming art lovers. I decide I’ll have to return another day to experience all of Picasso’s galleries—but I must see Guernica.

I need only follow the din.

We can hear the crowd from several galleries away. Late in the day on a Friday, everyone wants to see the famous painting. I am most excited because of its history, as laid out in Russell Martin’s Picasso’s War—an excellent history of why the painting was made and its complex life in the public eye.

Pictures do not do a work like this justice. Nor do crowds.

This work needs time and space.

Interestingly, the crowd has created a buffer at the front of the viewing.

The painting is twelve by twenty-five feet, and there is a cordon keeping viewers about ten feet back. Between the crowd and the cordon is a no-man’s land. I can only assume the crowd is being polite to one another—or perhaps they instinctively know they need distance to take it all in.

I decide that, in this moment, the more interesting aspect is the guards watching the painting and the crowd. So I turn my camera and my sketchbook on them, not Guernica itself.

In drawing, I begin to realize how important this is to the Spanish, and to humans in general. As I internalize how cruel humans can be, I am moved to tears—which I believe is exactly what Picasso intended. To affect the viewer.

Mission accomplished.

As the free hour triggers, the place becomes mobbed, and we decide it’s time to be somewhere else.

Dipping out of the museum, we drop into a McDonald’s for a snack and some warmth. Madrid has mastered the electronic order kiosk, which I loathe. I prefer human interaction. But I have to admit, as a non-Spanish speaker, the kiosk is much more efficient and less stressful.

This is how the robots win.

Wandering the streets until after dark, we find that instead of worn down, we are energized by the nightlife. My wife spots a Hard Rock Hotel, and we investigate the possibility of a live show. None are forthcoming.

So we decide to call it a night. Seven-thirty, cold and dark, and we are thin from the day’s museum visit.

As we try to figure out which bus will get us home to the Latin Quarter, I recall seeing an ad on the ride out. The bus in front of us had “CABARET—see it live” emblazoned in Spanish.

A quick search turns up that the Kit Kat Klub is in fact performing the show in less than an hour. We are only a thirty-minute walk away, but my wife—though excited and eager to see it—has no interest in trekking through Madrid that night.

So Uber it is. Mistake.

We’ve been operating under the assumption that traffic always flows. This is our first real experience with central Madrid on a Friday night. We live west of here, out of the tourist zone, where traffic is usually fluid. But here it is a grind.

We sit and sit as our driver battles it out. The worst part is watching the map as we inch to within fifty meters of the theater entrance, only to be pulled into traffic in a tunnel beneath the old town—where we’ve been drinking, eating, and living.

I want to jump out and dash to the theater, but instead we sit for twenty more minutes while he escapes the tunnel and gets stuck in a roundabout. We finally abandon him and make the ten-minute walk to the venue.

We are in luck—minutes to showtime. I misunderstand the clerk and instead of buying seats up close, I buy them in the back. Better, because there is less crush of bodies; worse, because I have not brought my distance eyewear and the whole show, while beautiful, is slightly blurry.

And speaking of the show—wow.

I expected half-measures with lots of reliance on titillation and suggested nudity, but to the director’s credit, they told a compelling story. Well sung. Well acted. Yes, the performers were stunning in their mostly naked states, and I applauded the daily work required to maintain such peak human form.

But by the third act, I was in tears. Blinding tears.

We started with a bottle of wine, and by intermission it was long gone, as were the two mini bottles of whiskey my wife smuggled in. Feeling no pain, we decided a second bottle of wine would be ideal to finish the show.

We should have stopped at one.

Inebriation heightened my sense of the story’s development. By the third act, I was undone. Up until then, everyone is managing—hiding in music, wit, appetite, motion. Then the story closes its exits. Pleasure stops being refuge and starts looking like delay.

Love and history arrive at the same moment and ask to be taken seriously.

What broke through for me was the quiet grief of realizing that fantasy can be sincere and still be unsustainable, and that some reckonings can’t be danced around forever.

My muse once said she identifies with Sally, and I understand why. Sally survives by keeping the lights on, by choosing momentum, by believing in the moment she’s standing in. Hitching rides with stars.

Watching it, I felt the pull of Cliff—not because I’m leaving or want to, but because I recognize the fear he carries: the dread that two people can love each other deeply and still not want the same future, or need the same kind of ground. The film touched that nerve—the uneasy knowledge that loving someone doesn’t always guarantee harmony, and that seeing clearly can feel like a threat even when it’s an act of care.

All this, in Spanish. I didn’t realize I had internalized the story so completely.

It was the emotional tearing that drowned that second bottle of vino.

When the performance ended, we stumbled into the night, red-eyed and full of yearning.

We should have gone straight home. But even close to midnight, Madrid was alive in a way we’d never seen. Plazas and avenues shot full of people. And so we swayed and danced in the streets like real Spaniards under the holiday lights.

It was magical.

Another stop at a pub added insult to our alcohol injury. By one a.m., we knew we were toast.

The glory of being completely smashed comes with hard consequences, and we both paid the price. My poor wife on a side street, revisiting the evening’s dinner and snacks. Me, once home, after she was safely in bed.

The old adage is true: beer then liquor, never sicker—or whatever idiom covers wine, then liquor, then wine, then beer, and the long night that follows.

At the very least, I made sure that before it all went quiet for the night, my feet were free and unencumbered for sleep. No amount of drink in the world can erase that need.

We’d had the experience of a lifetime in Madrid that day. It was among the highest highs of the adventure and the lowest lows.

I wouldn’t trade a thing.

Except maybe, save Sally from her sadness.

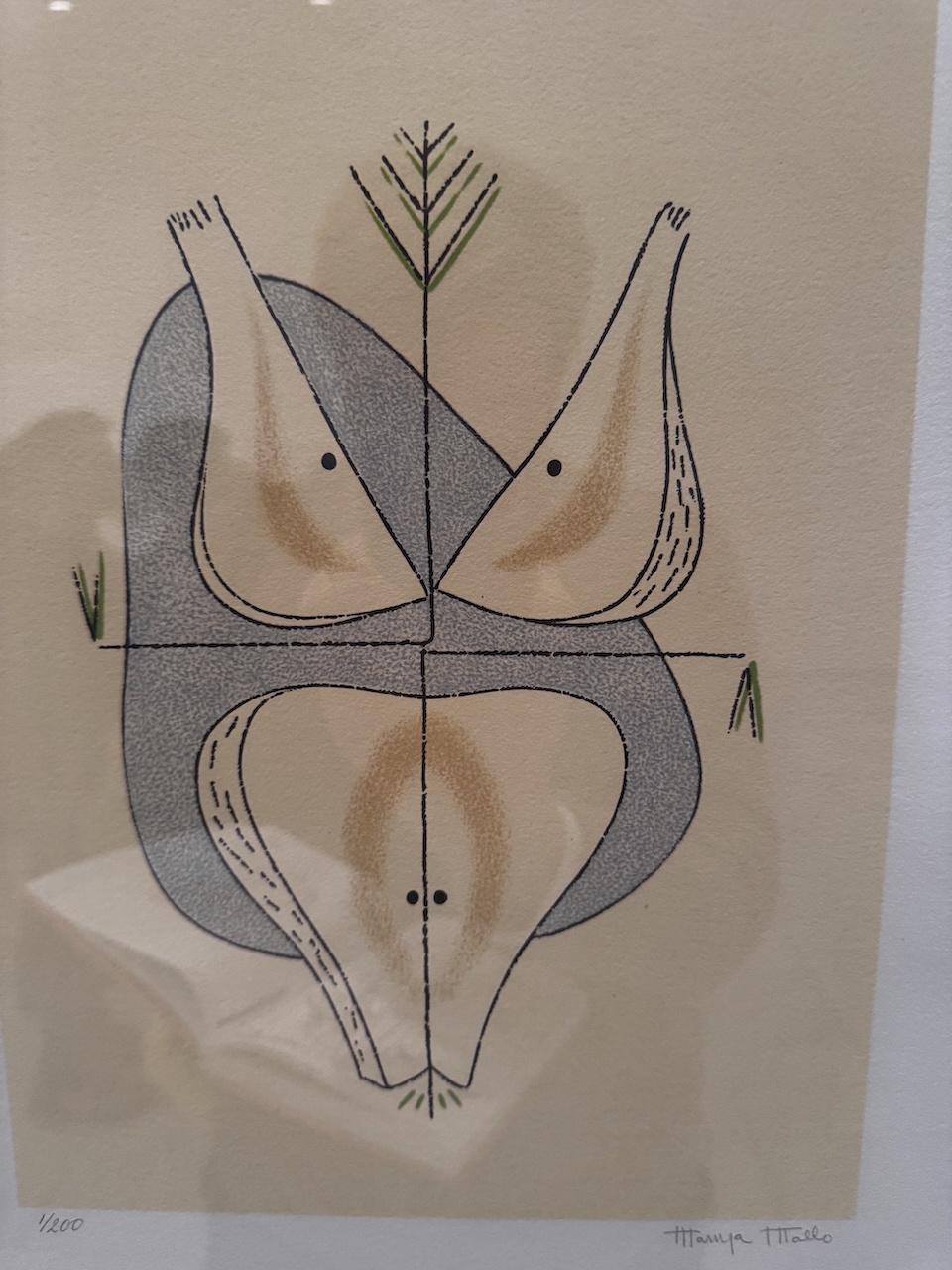

Drawing

WolfCast Home Page – Listen, follow, subscribe

Thank you for coming here and walking through the garden of my mind. No day is as brilliant in its moment as it is gilded in memory. Embrace your experience and relish gorgeous recollection.

Into every life a little light will shine. Thank you for being my luminance in whatever capacity you may. Shine on, you brilliant souls!

— Go back home and read MORE by Wolf Inwool

— Visit the archive

I welcome feedback at my inbox