Hive of Queens: A report on the Shared Visions Kick-off

From 23 to 30 April 2025, the kick-off of Shared Visions took place in Belgrade. The international team of visual artists, cultural operators, humanities scholars, web3 practitioners and activists gathered to set in motion the four-year project. From Zagreb, Croatia, Dina joined. Dina is a digital artist, producer, curator, a prospective member of the co-operative, and a long-term partner of the consortium. In this text, she reflects on the experience of the kick-off and the need for a transnational artist co-op from her personal experiences and perspectives of art work in the Balkans. What is the Shared Visions Co-op? Why should we care? How does it work? And what is in it for the co-operants?

(what gives)

After almost 20 years working with(in) the arts, you'd think you've seen it all. Often lagging institutional education and contemporary art museums equipped only for modernist work, heartfelt mentorship versus violent systematic exploitation, tons of experiments and mostly failures, in-kind supportive networks and various safety nets, non-existent markets, grey markets, black markets, racist markets, quantum markets, solidary markets, non-fungible assets, art as mere native ads, and so on. In it, my most honorable mention might go to our audiences sincerely looking to make their day better by enjoying etchings of cats, poetic deliberations in video arts, or faux Dali installations. And during this length of time of art-life causality, you're fully conditioned to grow as an artist, to grow your persona, to grow your art, to grow its representation, the myth, its value, and its worth. Yet what you most probably weren't taught is to observe its nutrients that make it be, the (infra)structure it lays and quite possibly builds upon, and the effect it might have on communities tempered by the hellfire of exclusionary neoliberalism, at times doused by deliberations of humanist studies and the participation of the arts in the systemic status quo.

To be considered an artist, you are expected to:

☙ eat crap, ☙ clean literal shit, ☙ meet avid collectors, ☙ endure avid curators, ☙ detest malevolent mentors, ☙ learn to avoid everyone, ☙ sleep in castles, ☙ sleep in trams, ☙ burn fingers, ☙ burn bridges, ☙ burn work, ☙ donate work, ☙ form bonds, ☙ fret frenemies, ☙ enjoy the system, ☙ rage against the system, ☙ ultimately get stuff done, ☙ question everything and nothing,☙ enact variations and combinations of all of the above.

While arts studies might universally be critical of various concepts, often they lack self-reflection in the sense that you might never learn about artistic organizational models in Balkan-based art schools. You might excel artistically in your MA studies, but never really understand how stuff (i.e. the arts system) really works and how it takes part in institutionalized systems. Normally this results in poor practices praying on young artists and volunteers, time organization and/or labour rights not even being addressed (ever), collaboration models spectacularly falling behind any lucrative model, egos being boosted, toxic relationships seeping in, artists moving out, culture suffering a constant negative selection as well as systemic erasure of practices sensitive to nepotism and other destructive -isms.

Simultaneously, the public has built an understanding of artists as a classless myth, lingering between the esoteric, privileged elite and archetypal, spiritual pathos. “Why would anyone make art, an activity so unnecessary in these times of serious crises, unless they are completely self-absorbed and manic..?” Yet in parallel, positioning artists within the working or lower middle class, by reconstructing the means of production, will always extort a chain reaction of disbelief, anger and, paradoxically, a disassociation between the public and the artist. It doesn't matter if the arts heavily participate in local economies, if they take part in professionalizing institutional networks of education/inclusion/production/etc., rely on work by very precarious cultural workers and partake in the labor market, if they're literally made by invested communities – there will always be an underpinning extractivist narrative attached to it externally from neoliberal tangents. “Because there must be an ulterior motive for you to make arts as nobody needs those; you must be eyeing a political position or finding a human ATM. Anyway, if your art were any good, you'd be rich already and we wouldn't even be having this dilemma.” These are fragments of my recent observations, empirically based on various public-private-civil attempts for unionising artists and cultural workers in the Balkans. Even in this relatively petite geographic area, the same issues are at different paces and stages, so the perception of this class dysmorphia might differ proportionally to the normalized levels of precarity within. One thing is sure – and that is that arts have never, except in wartime, been at a lower social position, and many organizations are recently actively working on rehabilitating this inner+outer power of independent artists and cultural workers. Younger generations still might be saved, if they don't all silently quit in the meantime (which they might and maybe should 💘). Maybe cooperativism just could be the way out and within; by working truly collaboratively and for a collective cause—we might rehabilitate a sense of art being a real (part of) community.

(wth is a co-op)

(and for whom)

If you have had contact with different types of organizations for/of artists (general NGOs, artist organizations, ARCs and any Artist-Run-* project or informal collective, studio, ensemble, troupe, etc.), you might fall into one or both of the two categories: (1) hell no, never again and (2) collectivism is the best thing that ever happened to me. In my experience, smaller and/or more flexible and horizontal “real” collectives might have a bigger chance of having a longer positive experience for all members. Vertically organized and over-regulated large faux “collectives” after any given time most often fall into the administrative trap where the bureaucratic jobs are professionalized to a point where the arts production is externalized and intentionally kept in a precarious, highly centrifugal loop so that it can't affect the higher grounds of the organizational clique. As an example, Croatian-based office jobs in culture might often be in the register of a permanent job and with a degree of certainty (even though still with a degrading minimum wage), which might seem like a privilege – contrasted with artists “gigs,” paid so low and so infrequently that they couldn't even be sampled via studies or kept by legislation.

If we accept labour activism in arts as a necessary upcoming Zeitgeist there is definitely one more aspect that often collides with any collective action – and that is union representatives historically chair-hopping between workers' representation and political subversion (i.e. intentionally being subsidized and tokenized for adversary political processes). All that being said, why would anyone want to be a part of a collective or take part in collective action/production? Isn't it all just for show?

Imho, cooperatives might be the (constructive) problem for all our (defeatist) solutions.

By mixing up the entrepreneurial ambition and social purpose, goal maximisation with democratic governance, contrasting creative industries to genuine cooperativism, and internalizing needs as opposed to commodification,

all while focusing on its members and local communities—cooperation might just be the mix of direct action within working for a living that we all need.

In a post-capitalist society, most governments (privileged ones that were able to provide a safety net for the arts) are considering (or have already cut) further neo-liberalisation of the artists' work, obvious especially in post-transitional countries that wish to “cleanse” themselves from a socialist connotation. Be it via not regulating exhibiting fees in institutionally governed events, cutting subsidies for projects, allowing production centralization and legalizing social rights racquets, or by introducing competitive tenders for creative industries, there is a clear and constant trajectory of dropping support for artists. I should mention there is a parallel of amazing UBI-like projects such as the Irish Basic Income for the Arts “BIA” pilot program, the Slovenian work stipend “Delovna štipendija za spodbujanje poklicnega razvoja profesionalnih ustvarjalcev v kulturi”, or the French unemployment insurance “L’intermittence du spectacle”, and probably many others. But these are exceptions that prove adequate support is not an overarching rule, nor the solution to all problems, and is not accessible to all artists all the time, as the recipient often has to meet quite opaque and systemically steep criteria to reach financial thresholds in their human right to create art. Once you are pushed to the market, you can invest some assets (work / time / art / money / etc.) into a co-op to collectively build a productive art-hive where you can expect an asset or monetary profit in an order of magnitude larger than a single person could ever be able to organize alongside their personal art-work (i.e. structure / networking / collectivism).

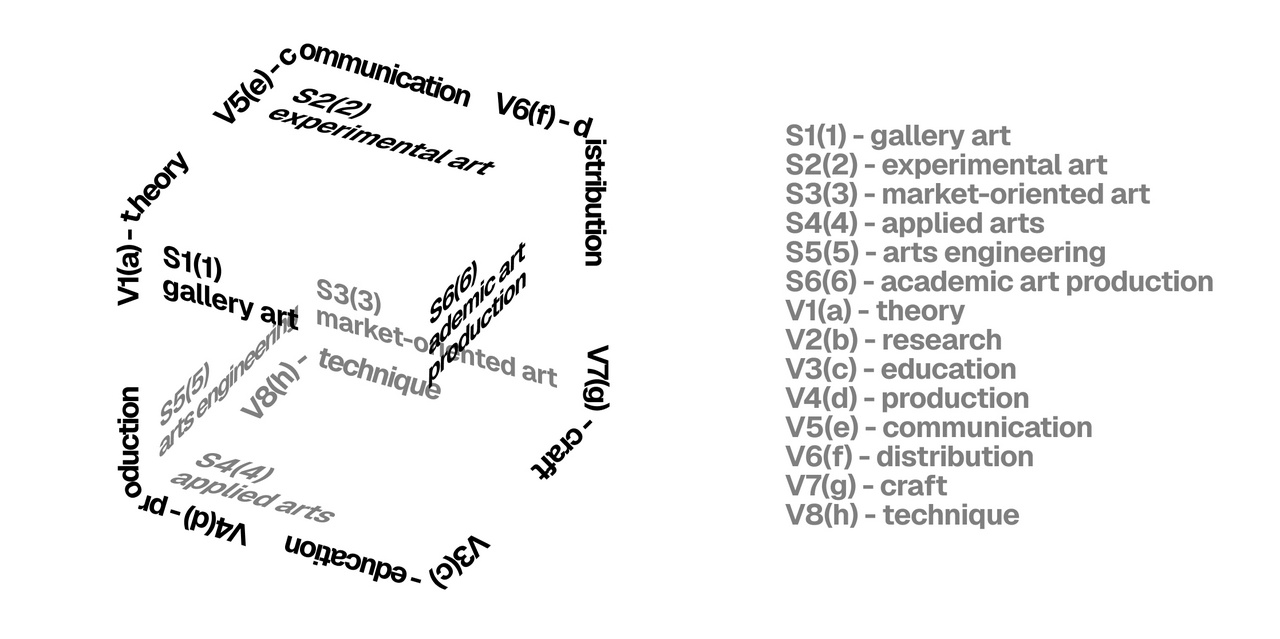

Once in a cooperative, you'd probably know and/or learn something about:

☙ non-market collaboration, ☙ collective needs (studios, legal support, pension systems) + mutual aid, ☙ secure and transparent digital infrastructure + digital commons, ☙ increasing public engagement with visual arts, ☙ more just and sustainable ecosystem in the art world, ☙ sharing the future of arts together, ☙ …

Cooperativism, at least in theory, could be an alchemic process in bringing in simpler material (our personal resources) to transform them into a more complex, solidary ecosystem that might hypothetically catalyse new, unimaginable assets. If you deem your work already gold and you are closed off to any collective input, co-ops may not be your cup of tea.

(what's in it for me)

For quite a long time (10 years now) I've been quite lucky to actively be a part of cultural production of a few international projects (e.g. Fubar), which always made painfully clear how different our intersectional positions are, with people spread out over the globe, in differing geo/socio-political or personal situations, some not allowed to create art, to travel freely, or even to receive payments for their work. This spurred my interest in exploring various organizational models that might help collectives in enduring these gaps and fissures, in co-organizing collectivist art as well as co-authoring production automation processes to rehumanise our P2P collaborations; yet real cooperative governance principles and practice – until my participation in Shared Visions activities – stayed beyond my grasp. Now my primary personal motivation in this project is to better understand the underpinnings of collective decision-making in a hectic real-life economic setting, as well as understanding the basic mechanisms and consequences of cooperative principles. These might all be set in motion on a social level, a technological one, or within legal structures.

I would also like to state that, even though I would prefer to be “only” an artist, I became a cultural worker and artists' union representative by accident. So please bear with me when we set some of the most frequently heard criticism of the “normal” arts systems:

☙ art production is often asymmetric, ☙ art market is exploitative, ☙ institutions are extractivist, ☙ individual production is sometimes inefficient, ☙ nonprofits are pretty separate from the private “real” sector, ☙ the system is ruthless, ☙ etc.

While you might hear of some advantages in collectivizing and cooperative practice:

☙ practices ethics in creativity in solidarity, ☙ brings international advantage, ☙ embeds multidisciplinarity, intergenerationality, transdisciplinarity, ☙ includes institutional misfits, ☙ nurturing for both professionals and creative working class people at an infrastructural disadvantage – political, chronological, geographical, institutional, economical, ...), ☙ etc.

Your motivation might be a different one; every participant of the Shared Visions kick-off week had a different position and expectation from the cooperative; some were interested in participating in the art market under fairer rules or to stir it up, some want to test alternative economies or extend interdisciplinary micro-organization, or to escape postcapitalist alternatives by pooling resources together, some want to support the political dimension of pan-European networking restoring solidarity, some were invested in collective production and decentralization, and were also pro democratization of the arts and integration of the marginalized, learning how to handle conflict and share privileges; while for some the benefits and value of the future co-op were left open and porous even though we all agreed that we need a political force for change and autonomy in this critical time of crises. Most friction in the collective discussions happened around the initial models of decision-making in constructing the pre-co-op infrastructure; questions were raised, stereotypes affirmed, privileges dismantled, and tones sharpened, yet the collective seemed to gradually absorb these different positions into a fluid compromise that left everyone equally unhappy (❤️🔥).

(how does it work the work)

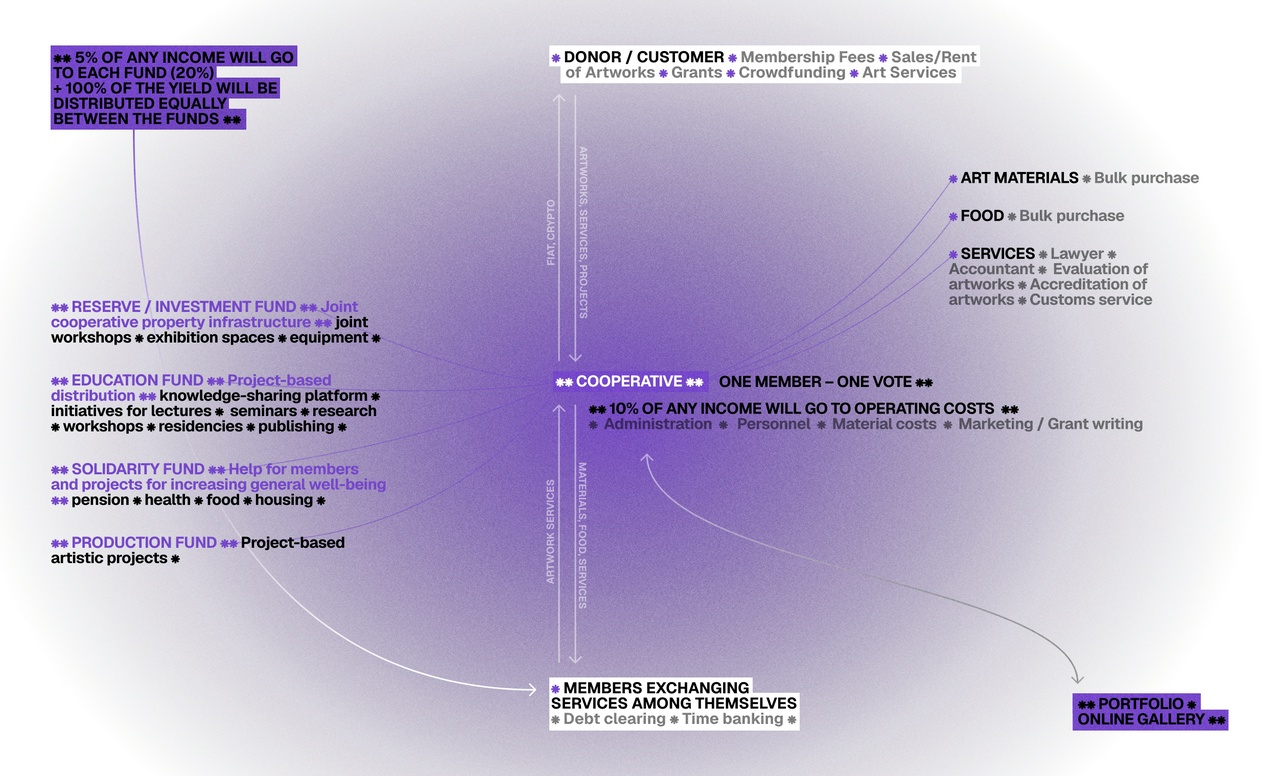

Once you deem you have enough privilege of patience and adequate emotional skills for a collective process (no pressure 💝 but hopefully you do or will), you're probably ready to join a cooperative. In the case of an artist-run co-op (such as the “Shared Visions” project future one), you will need to invest some resources to become a co-owner. This investment will be defined in the co-op bylaws and regulations, and will most probably be a selection or combination of resources such as time/money/assets/infrastructure/etc. Our primary motivation within (and beyond) the kick-off week meetup was to design this process as inclusively as possible, as there are many dimensions of systemic and circumstantial disadvantages in art-work, and we do not want to exclude underprivileged artists. Anyway, as the co-op is a market-oriented subject, it needs to have a certain degree of fiscal liquidity and inner stability or otherwise it would fail immediately, so fine-tuning this process is quite important.

(participation)

The next biggest question is, of course, the cooperative governing model and how to actively take part in running an organization. Co-ops are by law democratically governed, which means that each member, regardless of their investment, has a single vote. Theoretically, this is indeed most fair, but we also discussed how in practice these systems are often hacked by soft power, lobbying, bullying, and other time-based power techniques. We also invested a lot of time to discuss our different contexts and how to overcome or override them; which types of cooperation are expected and how can these e.g. fiscally, flow from one country to another, especially giventhat Serbia is not economically part of the EU. There is a lot to define and to be desired in this area; I feel a lot of time in designing the cooperative will be (hopefully fruitfully) invested in this multidimensional topic.

(management)

Once you have defined your non-technological problem, that might be the best time to introduce a technological problem to follow up on par. Of course, the tech dimension of any project will shortly make it harder as it makes the inner workings visible, but it is also there to ultimately make your work better and easier to manage long-term. Plans for the future co-op are to be decentralized and heavily digitized based on DAOs and the commons, to empower its members and to enable internalization of member assets and services. That means that any artist joining the future co-op should be able to reliably vote digitally, charge for services internationally, and exchange assets internally, minimizing cross-border expenses where possible. A lot was discussed and scenarios were heavily LARP-ed in practice, yet tons of topics are left open for future discussions as web3 and the blockchain are constantly in flux – with all its many crypto-ethical+eco-political+socio-economic golden strings still pulled by human desires.

(collectivism)

Artists could participate in the coop by offering infrastructure, providing services, investing hours, selling work, or a combination of all. We might project that the variations might be as many as the number of co-op members. New members would also have an intro period where they would receive education on cooperativism, as well as opportunities for practical mentored work in the co-op projects. Members could also work together, support each other and be included within others' projects dispersed over the European continent and beyond the horizon of neo-liberal competition. This would hopefully strengthen the collective spirit and forward the co-op altruistic agenda, further emancipating its members. In this process of creativity and solidarity we aim to achieve equilibrium and equity for artists living and working between different realities. After we master that, all that is left is to figure out how to bring peace to the rest of the world. 💜