Offer, Exchange, Take Away: An Experiment Worth Pursuing

Report by Milan Đorđević, Tijana Cvetković & Noa Treister

Building the cooperative did not begin with a strict program but with a series of conversations about how artists might reorganise their work and the relationships around it. So, this text turns to one specific attempt to rethink artistic exchange and the conditions under which art is produced and circulated in Serbia.

Our research study within the Association of Fine Artists of Serbia (ULUS, 2023) has shown that the visual arts field is marked by a high level of centralisation, dependence on a few major institutions, and the gradual erosion of public cultural infrastructure. As market logic expanded into areas once shaped by collective investment, cultural participation narrowed, particularly for the working class. In such a landscape, artistic value tends to be defined by visibility and demand rather than by social relevance. This is the background against which we began to explore whether practices of exchange outside the monetary frame might open different relationships between art and its surroundings.

In defining the scope and modes of operation of the co-op, we began to experiment with barter as a tool for rethinking exchange. The question we placed at the centre of this process was simple but fundamental: how can barter, as a form of non-monetary exchange, function both as a critique of existing art economies and of the way they define the role of art and artists in society, while also prefiguring alternatives?

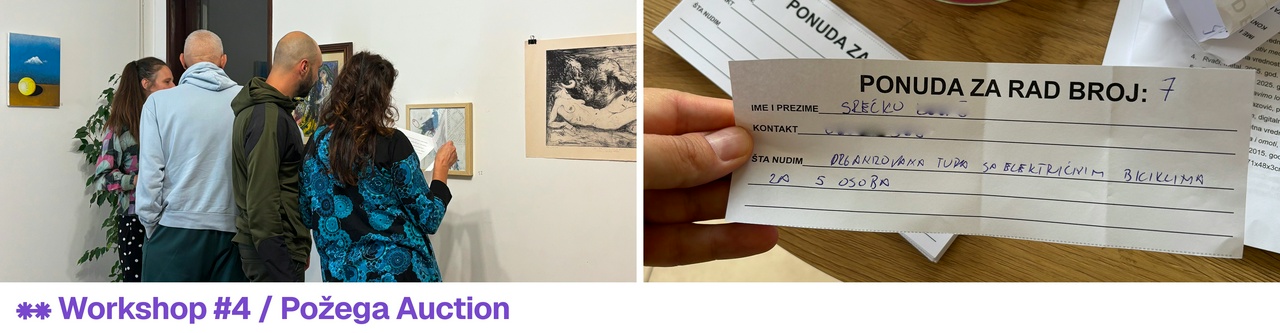

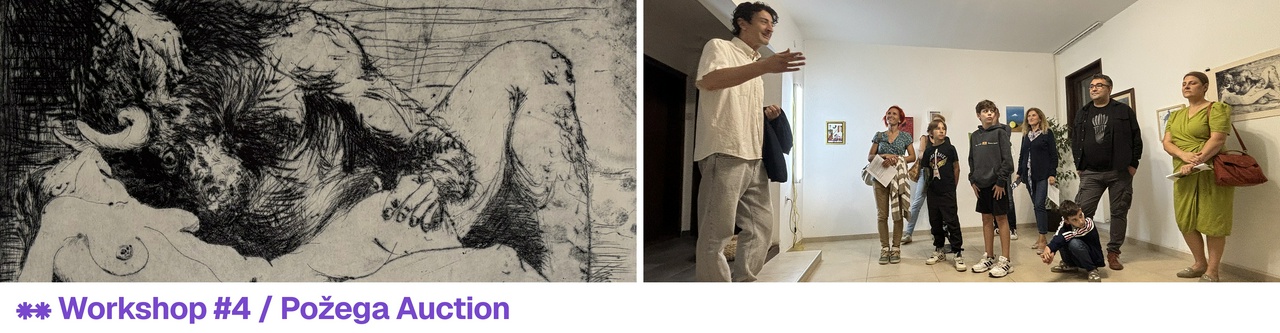

Our first public experiment was conducted in Požega in the autumn of 2025, under the title Ponudi, razmeni, ponesi – Offer, Exchange, Take Away. Visitors were invited to offer something of their own in return for an artwork. It could be a haircut, a home-cooked meal, help with repairs, a professional service in a non-art-related field, or money if they wished. The format resembled an auction, but its rhythm and meaning were different. Each artwork was accompanied by space for offers; after the exhibition closed, the artists reviewed the proposals and decided which to accept.

The exhibition took place in a space that had previously been a hair salon in the centre of Požega. It had been empty for months, and the owner was considering turning it into an art space. That circumstance gave us a kind of freedom that is rare when working within established institutions. There were no curatorial or administrative expectations, only the practical question of how to make the exchange visible and accessible. We organised the exhibition to be open a few afternoons and evenings during a period of three weeks. A person from the local community was engaged for a modest fee to keep the space open, welcome visitors, and explain how to make an offer and how the exchange would unfold. At the same time, we promoted the event through social media, direct letters sent to local entrepreneurs, and through personal networks. In small towns like Požega (≈12,300 inhabitants), we realised that word of mouth still functions as the most effective form of public communication – slower but more durable than any campaign. By the end of the three weeks, around fifty people had visited the space, and several of them made their offers.

After the exhibition, we gathered for a workshop that opened one of the most persistent questions among artists: how to define the value of one’s own work. Most participants admitted they find it difficult to put a price on something that does not fit into standard market categories. One artist said she rarely sells her work as an object, and that her decisions depend on “who approaches her and whether they understand each other”. Others spoke about the challenge of balancing artistic integrity with livelihood. As one participant noted, “you can’t measure everything in hours, but you can’t ignore the time and materials either”.

For us, this conversation was central. A cooperative is not built around the idea of profit but around the need for sustainability. As we discussed, we don’t have to be profit-oriented, but we do have to cover our basic living costs. This simple statement cuts through much of the ambiguity that surrounds the notion of artistic value. It recognises that art, like any form of labour, depends on material conditions, but also that value is not fixed – it is negotiated in relation to others, to context, and to shared purpose. And barter became a way to make these relations visible: a two-day truck trip to Durrës in Albania; twenty professional hair colorings and haircuts with no time limit; a curatorial text for the next exhibition; documentation for building legalisation up to 200 square metres; a personal herbarium; a weekend stay with breakfast for up to eight people, and many more proposals that carry different understanding of value and relation. None of them could be translated neatly into monetary terms, and that was precisely the point. The exchanges showed what people were ready to give and how they imagined their connection to art, as care, as time, as skill, as hospitality. Whether professional artistic work becomes a matter of survival arithmetic (as was mentioned during the workshop) or remains unrecognised as labour, the question is the same: how to live from what one creates. As one artist put it, few people see art as work at all, and that is precisely where the cooperative finds its role – to shift perception and rebuild the link between artistic value and the conditions of life that sustain it.

Even though some visitors offered money for the artworks, the non-monetary exchanges shaped the atmosphere of the event in a different way. Instead of fixed prices, artists provided approximate starting points for negotiation, which opened space to focus less on monetary value and more on the people who approached them. Buyers were no longer anonymous figures but individuals whose interests, skills or forms of care said something about why they wanted a particular work. Several artists accepted offers that were modest or unconventional, simply because they felt a sense of recognition in them. From a conventional entrepreneurial standpoint, accepting less than the assumed market value might be seen as diminishing one’s worth, but this concern did not play a central role here. The exchange was not framed as a market transaction to be optimised, but as a space in which value could be shaped through relation rather than price. That shift loosened the usual distance between artist and audience and made the encounter feel grounded in mutual attention instead of market logic.

The co-op should bring artistic labour back into the everyday economy of life and exchange, without romanticising precarity or denying the need for income. Its way of selling art should test how art might live when its value comes from relations rather than from market recognition. This intention became clearer when we proposed to repeat the experiment in one of the central art spaces in Serbia. The response from its curators exposed precisely the tension we wanted to address. They worried that the idea of exchanging artworks for homemade goods or services could “devalue” art and “encourage amateurism”. Their concern was not unique; it reflected a broader institutional anxiety about how artistic value is defined and protected in a system that already struggles to sustain its own workers.

What the experiment left us with was not a ready-made model but a clearer sense of the questions that need to be worked through: how to organise exchanges that recognise artistic labour without falling back on market metrics; how to involve communities without reproducing hierarchies; and how to build structures that make such practices sustainable rather than exceptional. For the next iteration of the exhibition, we turned to a public library in Bor, a mining town with a growing community of Chinese workers, as a place to continue the experiment. The interest shown by artists during the open call, their questions, suggestions, and willingness to engage even when they could not participate, confirmed that the need for such spaces is real. Rather than closing a cycle, the workshop and exhibition in Požega marked the beginning of a longer process; in the coming period, we plan to develop a series of these kinds of events that deepen this exploration of alternative economies of art.