Shared Visions reading ‘Artists, Activists, and Worldbuilders on Decentralised Autonomous Organisations’

reading group report by Alessandro Y. Longo

Not having a measuring tape to measure a table does not mean the table does not exist. – Dayra

Shared Visions aims to establish a transnational cooperative for visual artists that integrates expertise from digital commons and Web3 communities to co-design a secure and transparent digital infrastructure for internal decision-making and resource sharing. As part of Curve Labs’s contribution to Shared Visions, Erik Bordeleau and I decided to organise a reading group, hoping to cultivate a shared understanding about the possibilities and limitations of working with the blockchain.

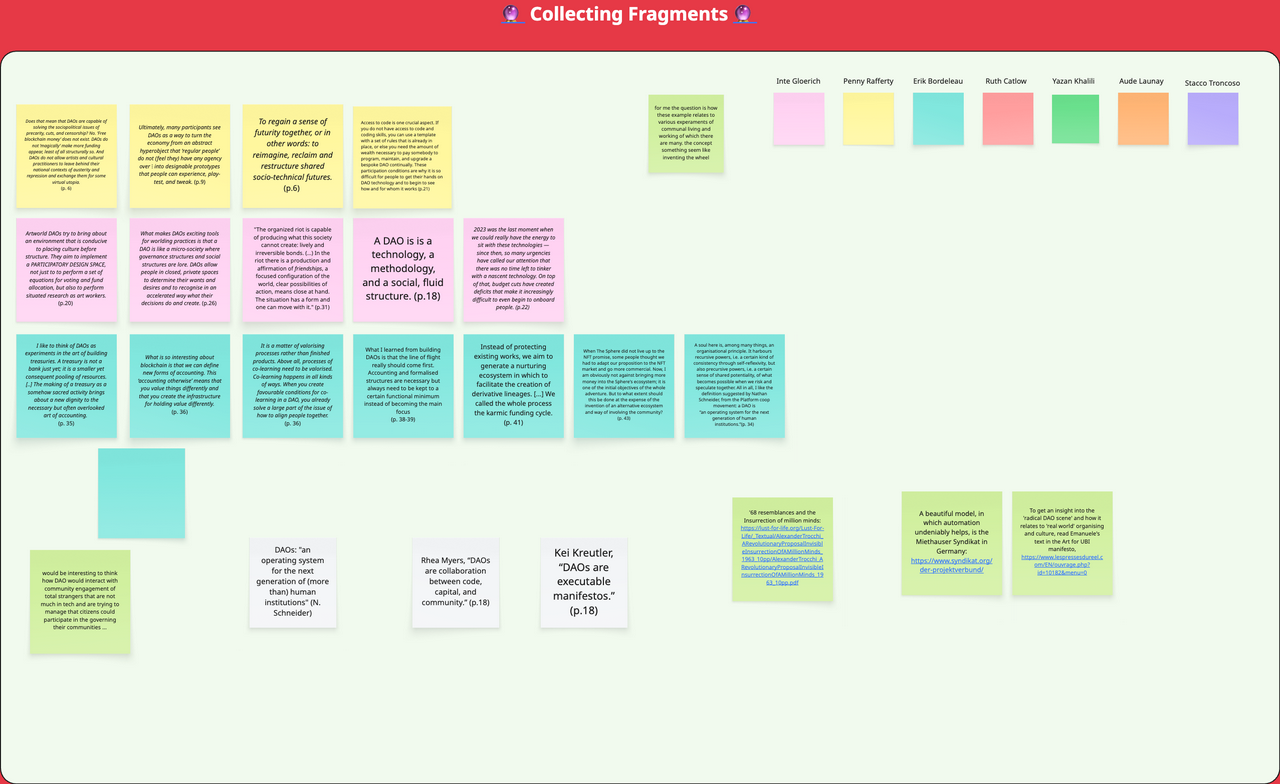

In the first reading group of the Shared Visions project, we read Artists, Activists, and Worldbuilders on Decentralised Autonomous Organisations: Conversations about Funding, Self-Organisation, and Reclaiming the Future, edited by Inte Gloerich. Published by the Institute of Network Cultures in 2025, this collection of interviews explores how Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) and other participatory structures can help artists and cultural workers reclaim agency in their economic and creative lives. The interviews present some of the most intriguing experiments happening at the periphery of the crypto-sphere, where artists, organizers, and technologists try to design and build alternative economic models for sustainable cultural work, leveraging blockchain technologies to build resilient frameworks for communities facing increasing precarity and fragility. In Gloerich’s words, these ‘artists and activists engage critically with the socioeconomic setup of their sector, activate communities and collectively build tools and infrastructures to prefigure different futures.’

It therefore felt natural to collectively read Gloerich's book as an accessible and comprehensive overview on these communities, to spark the imagination of what would be possible for Shared Visions and foster constructive dialogue among these digital-driven experiments and the wealth tradition of cooperative and mutual-aid mechanism and structures that many of us at Shared Visions know well.

The reading group was structured across four meetings, each dedicated to exploring one of the volume's key interviews, beginning with Penny Rafferty's reflections on Black Swan DAO, moving through Erik's account of The Sphere and Ruth Catlow's work on CultureStake, and concluding with Yazan Khalili's vision for Dayra. While the four projects span different geographies and contexts – from Berlin’s art scene to the Occupied Territories of Palestine – they all share a similar approach to blockchain technology and the idea of DAOs.

Some words on what a DAO is. Think of a DAO as an online-first organization, where a group of like-minded people pool together resources to achieve some kind of goal (e.g., buying the US Constitution or supporting artists). Usually, the resources are collected in cryptocurrencies, and they are administered collectively through a voting mechanism (e.g., quadratic voting). The ‘A’ in DAOs stands for autonomous and suggests that many of these organizational processes can be automated by using smart contracts, that is, a fancy name to define computer programs built on the blockchain. The automation can look a lot like an “if-then” statement: if X number of people vote for this proposal, the funds are automatically sent to this wallet. What makes DAOs distinctive is their combination of transparency—all transactions and votes are recorded on the blockchain for anyone to see—their potential to operate without traditional hierarchies or central authorities, and their capacity to enable coordination among people who may never meet in person but share common goals.

It shouldn't come as a surprise, then, that the idea of DAOs ignited an imaginative fire in the art world, where questions of funding, gatekeeping, and democratic participation have long been pressing concerns. For artists and cultural workers facing shrinking public support, censorship, and exclusionary institutional practices, DAOs offered a compelling vision: what if we could design our own systems for collective decision-making and resource distribution?

Through this creative appropriation, artists enriched and amplified the meaning of DAOs; in the book, Penny Rafferty defined them as “a technology, a methodology, and a social, fluid structure.” The idea behind these new organizational forms is to multiply spaces of agency from the bottom up, holding space for more participation in what are usually conceived as vertical processes like cultural planning, assignment of funding, and more. This is, in essence, why we approach blockchain technologies with critical curiosity: as an infrastructure for creating what our friend Josh Davila (The Blockchain Socialist) calls small “units of use and capacity”, allowing us to develop, as autonomously as possible, the social, economic, and cultural frameworks we so desperately need. The reading group proved instrumental in amplifying our distinct perspective on blockchain technologies, one deliberately disaligned from the nihilistic, hyper-financial, and increasingly US-centered approach that dominates “mainstream crypto”.

But perhaps an even more crucial lesson we drew from the book is not to position “structure before culture”, challenging the romantic rhetoric that often surrounds both DAOs and intentional communities, in and out of crypto. Effective organizations aren't just collections of like-minded people, but groups bound together by material conditions and necessity: a culture of shared necessities and visions for how to overcome them. Erik's quote from The Invisible Committee about creating “lively and irreversible bonds” reminds us that what we're really building isn't technology but relationships robust enough to outlast any particular platform or protocol. An exceeding, ineffable element will always escape attempts at coding it, whether via computer language or governance protocols. Desire is not measurable, and infrastructure cannot be sustained if we don't keep cultivating and tuning the social garden of a group.

Imagination and culture, technology and law all intertwine in the fabric of the possible for an emerging organization like the Shared Visions Cooperative. This reading group has helped us as an organization come together, exchange knowledge, doubts, and ideas. Looking ahead, these discussions have also clarified the practical applications of Web3 technologies for our cooperative: transparent and weighted voting systems that can account for geographical proximity and local needs, automated protocols that can distribute resources based on collectively agreed criteria, and blockchain-based systems that make collective ownership possible across national borders. As Erik suggested, DAOs might offer the infrastructure for “co-op 2.0”, providing new affordances for “accounting otherwise” and navigating across the fragmented legal and financial systems of contemporary Europe.

In this process of becoming a collectivity, we move against the currents of desperation and hopelessness that characterize our times. We design for agency while facing our helplessness, as Noa reminded us in the last meeting. To build something together is to hope for the future.