The Artist Cooperative as Collective Agent: Report of Radionica #1

Milan Đorđević, Noa Treister, Tijana Cvetković, June 2025.

There is no shortage of collaborative projects in the arts. But few of them lead to collective structures that support artists beyond the lifespan of a single project. It often sounds progressive and promising – until someone asks what exactly we’re cooperating around, who will take care of the boring parts, or how the bills will be paid.

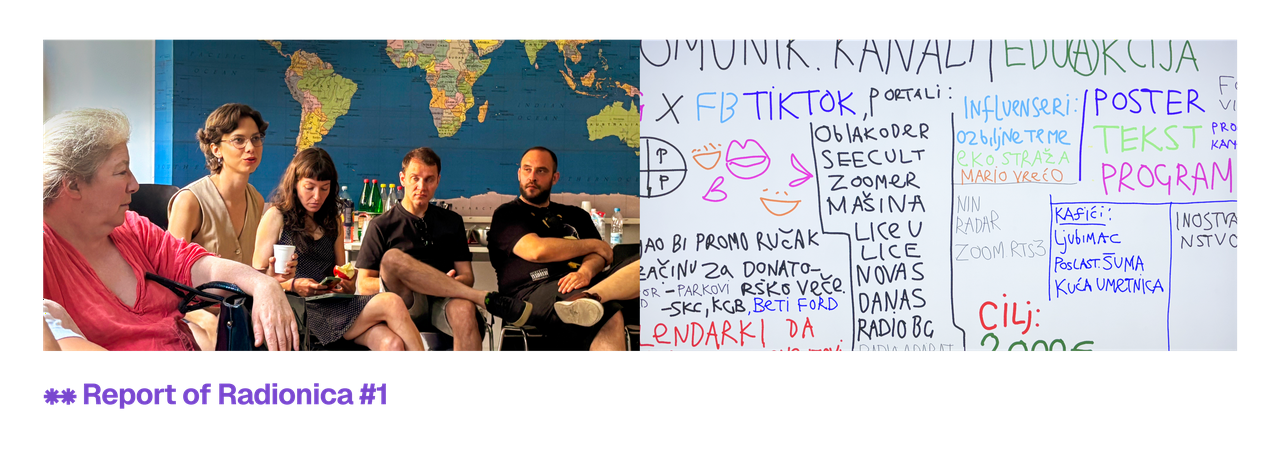

Within Radionica #1 held in Belgrade in June 2025, we gathered to discuss the structure of a future artists’ cooperative that we are trying to build – an actual legal entity with membership, a revenue model, defined responsibilities, and functional governance. The entity that may one day be capable of buying a printer, covering rent, or paying an artist’s fee without unnecessary complications.

What follows is an account of what we did over the long weekend – it’s not a tidy report, but a blunt reflection of a work in progress. It documents the workshop, the cooperative we are building, and the ongoing lessons we are learning together.

This workshop was our first dedicated session on exploring the economic foundations of the cooperative. We asked: How will it generate income? Where will that income be allocated? What kinds of funds should be established, and who will decide their use? Could such a structure genuinely improve our livelihoods? We began by outlining the basics – income streams from membership fees, grants, crowdfunding, sales, and sponsorships, with ten percent of all income designated for operating costs. Beyond that, we discussed the anticipated system of internal funds aimed at supporting art production, fostering solidarity, promoting education, and making strategic investments.

Participants formed small groups and were invited to design concrete project ideas that would address a specific (social) issue or engage a community in a meaningful way, and would cost no more than 500 euros. These weren’t abstract proposals or concept notes, as the goal was to imagine something that could realistically be carried out and collectively supported through a crowdfunding campaign.

Each group took a different direction: one group focused on food inequality in Belgrade’s peripheral neighbourhoods – areas where access to fresh produce is limited, unlike the more privileged central districts. They proposed creating public, edible gardens in collaboration with local schools: spaces where fast-growing vegetables and fruit-bearing plants could be cultivated with and by children. This idea merged urban gardening, eco-sustainability, and social justice into a single gesture of reclaiming unused land.

Another group explored digital exclusion among artists, particularly those of older generations, or simply those without the time, skills, or resources to build an online presence. The premise was simple: if you’re not visible online today, you’re often invisible in the art world entirely. The group’s idea was to form a support team within the cooperative that could help these artists with digital visibility: from setting up websites to formatting portfolios, and even learning how to navigate platforms for presentation of their art. During the discussion, it became clear that the idea stemmed from the younger artists’ concern for the digital invisibility of their mentors and older colleagues, whose work remains undocumented online. The project thus highlights intergenerational redistribution of resources and skills, and addresses the unequal conditions of visibility in the art world – both of which are inherently political. It also opens the possibility for the cooperative to act as a facilitator of peer-to-peer services, coordinating support and potentially formalizing such exchanges as part of its internal economy.

The third group proposed a talk show in the format of a local, grassroots podcast – a kind of “kafana conversation” (kafana – traditional Balkan tavern), where people from outside the usual expert circles could talk about current social and political issues. The idea wasn’t to parody professional media, but to open up a different kind of media outlet, where conversation flows more like it does in everyday life. This proposal emerged in the context of the ongoing protests against the national broadcaster RTS, criticised for failing to provide proper coverage of the student demonstrations and broader social discontent. At the same time, the format resonates with the recent emergence of local assemblies and plenums across Serbia, where citizens have been gathering to practice forms of direct democracy outside institutional frameworks. In this sense, the podcast aims to mirror and support these decentralised spaces of political expression.

The third group proposed a talk show in the format of a local, grassroots podcast – a kind of “kafana conversation” (kafana – traditional Balkan tavern), where people from outside the usual expert circles could talk about current social and political issues. The idea wasn’t to parody professional media, but to open up a different kind of media outlet, where conversation flows more like it does in everyday life. This proposal emerged in the context of the ongoing protests against the national broadcaster RTS, criticised for failing to provide proper coverage of the student demonstrations and broader social discontent. At the same time, the format resonates with the recent emergence of local assemblies and plenums across Serbia, where citizens have been gathering to practice forms of direct democracy outside institutional frameworks. In this sense, the podcast aims to mirror and support these decentralised spaces of political expression.

The final project responded to the same political moment. During ongoing student protests in Belgrade, a pro-government counter-camp was erected in a public park – a performative occupation nicknamed “Ćaćilend”, staged by football hooligans and nationalist-affiliated groups, which blocked access, caused visible damage, and turned the space into a political stage. Once the camp is dismantled, a large amount of physical debris will remain. This group proposed reclaiming the site by repurposing leftover materials – tents, tarps, poles – and collaborating with the local community to build a public sculpture. It would serve both as a trace and a transformation – an artwork born from conflict, intended to open a new chapter in how the space is remembered and used.

Once all four project ideas were on the table, the discussion emerged: if these projects were to be presented together as part of a single crowdfunding campaign led by the cooperative-in-formation, how do we do that without forcing coherence where it doesn’t fully exist? How do we respect the particularities of each project, yet communicate them as part of a coop effort? While questions were raised about whether some ideas might be more suitable for the cooperative than others – and what criteria could guide that assessment – the decision was made not to limit support to a single project. Originally intended as a selection process from a larger pool, the final set of four projects reflected the fluctuating number of participants. There was no final answer, but the discussion sharpened the questions we need to keep returning to: What does it mean to produce art as a coop, rather than as a sum of individual practices? Why do we need a cooperative, rather than simply supporting each other’s projects informally? And what exactly is it that none of us can do alone?

In trying to answer these, it became clearer that we are not just talking about financial models or campaign strategies. We are talking about a shift in position – from the artist as individual producer to the cooperative as collective agent. The cooperative we are building shouldn’t just be a service platform. It will be a political subject in its own right, that embodies values that are increasingly difficult to sustain alone: redistribution, mutual care and long-term sustainability.

In trying to answer these, it became clearer that we are not just talking about financial models or campaign strategies. We are talking about a shift in position – from the artist as individual producer to the cooperative as collective agent. The cooperative we are building shouldn’t just be a service platform. It will be a political subject in its own right, that embodies values that are increasingly difficult to sustain alone: redistribution, mutual care and long-term sustainability.

Another question – one we barely touched – concerns the livelihood of the participating artists. The proposed budget for each project, as discussed earlier, was set at 500 EUR. Apart from one group that, at least symbolically, included artist fees in their plan, all others seemed to take for granted that the artistic work would be done voluntarily. This raises important concerns when viewed through the lens of a coop structure. Avoiding the liberal impulse to individualize responsibility or romanticize sacrifice, we asked instead: Should the cooperative only support projects that can afford to remunerate artistic labor? Should membership be limited to those whose work can contribute to the collective income?

While artists have always found ways to collaborate – often under the radar, in temporary formations or through networks – the cooperative structure offers something more sustained. It opens up the possibility of building a shared infrastructure through redistribution and solidarity economy within itself, which should reduce precarity, increase access to resources, and not depend on institutional gatekeepers or market trends. The general mission is straightforward, even if the work to get there isn’t: to improve the lives of artists and foster ties with communities around them. Whether that means lowering production costs, expanding access to tools, spaces or food, offering legal and technical support, or simply making sure that more people can afford to participate in art consumption, the cooperative – with each income stream, including one-off campaigns like crowdfunding, contributing a percentage to coop shared funds – is a way of holding that mission collectively, over time.

This is especially relevant in a regional context severely affected by neoliberal transition, austerity, and deepening inequality in all spheres, where art has become more and more reserved for the urban middle class, while working-class people have been systematically excluded. Rather than relying on abstract ideals of inclusion, the cooperative model points toward a reversal made possible through concrete, collectively built structures.  This workshop, then, was a small step toward one. While rooted in the local context of the Balkans – where cooperative organising among artists is rare and the term itself often evokes agricultural or historical models – Radionica #1 served as a testing ground for deeper engagement with cooperative principles. It is part of a broader onboarding process for future members of the international artists’ cooperative we are building. Rather than starting from abstract frameworks, the aim was to collectively think through the material conditions of artistic labour, shared authorship, and sustainable production – and to do so in direct relation to participants’ real experiences and political contexts. In that sense, the workshop was less about prototyping projects and more about shaping a collective subjectivity fit for cooperative work. Similar onboarding processes (often lasting months) are common in cooperative ecosystems elsewhere, and this initiative follows that logic: preparing a foundation where each member understands the structure and their role and responsibility within it.

This workshop, then, was a small step toward one. While rooted in the local context of the Balkans – where cooperative organising among artists is rare and the term itself often evokes agricultural or historical models – Radionica #1 served as a testing ground for deeper engagement with cooperative principles. It is part of a broader onboarding process for future members of the international artists’ cooperative we are building. Rather than starting from abstract frameworks, the aim was to collectively think through the material conditions of artistic labour, shared authorship, and sustainable production – and to do so in direct relation to participants’ real experiences and political contexts. In that sense, the workshop was less about prototyping projects and more about shaping a collective subjectivity fit for cooperative work. Similar onboarding processes (often lasting months) are common in cooperative ecosystems elsewhere, and this initiative follows that logic: preparing a foundation where each member understands the structure and their role and responsibility within it.